A few days ago, I was daydreaming at work and a person came up to me and asked me what I was looking at. I told him that I was not looking at anything in particular but rather just daydreaming. The person then proceeded to ask me where I was from. I hesitated for a second and I told him I was American, but then proceed to correct myself telling him I was Chinese-American. But he asked me again where I was from and I told him I was born in the United States but I am ethnically Chinese. After that, he asked me where my parents were from and I said China. He then stated that “so you are Chinese,” and I said yes but repeated myself again telling him that I was Chinese-American. He then said something that appalled me. He told me, “You are where your parents are from.” After the end of that conversation, I began to wonder how someone can be so ignorant. Just because I am ethnically Chinese does not mean that I am only Chinese and identify with nothing else, especially for someone who does not even know me to tell me that I am Chinese and that is it. In this day and age, it is nearly impossible for a person to only have one identity, yet this person proceeded to conclude that I could be nothing more than that. At the end of that experience, I could help but feel offended by that person’s statement and feel bad for his ignorance.

.jpg)

Fu Zhou

This is just one of the struggles that Chinese-American immigrant children deal with on a regular basis according to Karen Lam when I told her about my experience. Karen told me that during her transition period in the United States, she also had similar experiences. As a young child, she often felt hesitant to answer the question, “Where are you from?” The complexity of her background makes it hard for her to pick one or even two countries to identify with.

Karen’s parents are originally from the Fu Zhou province of China. Both of her parents lived in different parts of the same province but both eventually moved to Hong Kong. Her father moved from Fu Zhou to Hong Kong because his entire family relocated to Hong Kong for economic reasons. Karen’s mother moved to Hong Kong because Karen’s grandmother got a visa that would allow Karen’s mother to relocate to Hong Kong as well. Karen told me that her mother moved to Hong Kong because her mother thought that she was still young and it would be a good experience for her. Karen’s parents met through a connection that connected the two parties and her father and mother fell in love at first sight. In Hong Kong, Karen’s mother started working as a saleswoman knowing little Cantonese and learned the language as she worked. Eventually, her mother got promoted to a secretary of a small company but one that paid well. Karen’s father was a truck driver by day and a taxi driver by night. After living a few year in Hong Kong, Karen’s mother was eventually pregnant with her.

Local Hong Kong Street

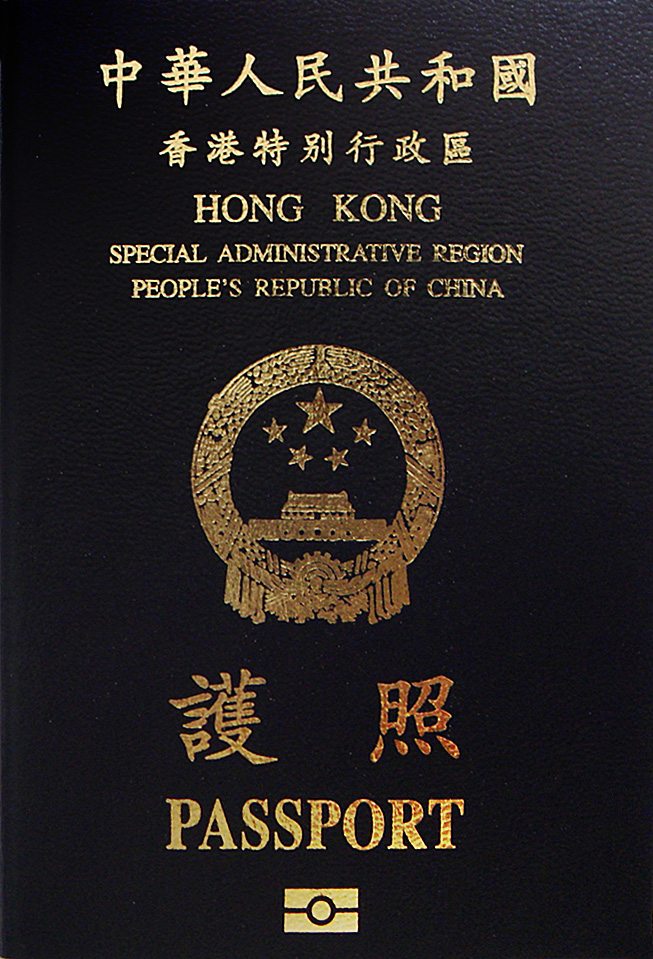

Karen was born in Hong Kong and has a Hong Kong passport. But at this point, Karen does not only identify with being a Hong Kong native, but also an ethnic Fuzhounese. To Karen, being Fuzhounese means being a traditional Chinese, meaning she shares the food and culture with her traditional Fu Zhou background. In addition, she also knows all of the regional traditions that Fu Zhou people have. Being born in Hong Kong means that she adopted western ideologies and ideas. Living in Hong Kong was a stepping stone for Karen because eventually she will also move on to identify with being an American as well. Because of Hong Kong’s history of being in and out of British and Chinese control, Karen deeply connects with the dual identity aspect that Hong Kong gives her.

Hong Kong Passport

Karen’s American journey began when her father went to American to “check out” the businesses in America. At the time, Karen’s uncle was already settled in America and owned a laundromat. When Karen’s father arrived in the U.S. he lived with Karen’s uncle and trained at the laundromat, learning the necessary skills needed to run a laundromat. After about eight months, Karen’s mother also traveled to America to meet up with Karen’s father to learn the same skills that her husband learned. Eventually, Karen’s mother and father moved out of Karen’s uncle’s house and got their own apartment in Astoria. They eventually opened up a laundromat of their own as well. Meanwhile, Karen was still living with her grandparents and going to school daily in Hong Kong.

During her parent’s time in the United States, Karen’s mother also gave birth to Karen’s little sister, Pinkey. Almost immediately after giving birth to Pinkey, Karen’s mother returned to Hong Kong where she stayed for another year or two before permanently relocating to the United States. Karen remembered when she arrived, everything was already prepared. Her family already had their own business and home and did not struggle financially. America to Karen meant a new beginning and a new chapter in her life. Karen also attributes her adventurous side to her American identity due to the fact that America is the land of opportunities and she is constantly on the hunt for new opportunities.

Karen and Pinkey

Once Karen arrived in New York, I asked her if there was anything that she struggled with and she told me there wasn’t much that she struggled with. Karen told me that when she had arrived in the United States, her parents had already set up their business and had a place to live. There was essentially nothing to worry about. For most of her life, the one thing that she had to do was focus on her studies. Karen did not struggle with English or “assimilation” in the United States.

“In Hong Kong, I would go to prep from 8-11am and then my grandparents would pick me up and feed me breakfast. After breakfast, I would put my uniform on and go to school form 12-6pm.”

“Prep (prep is what we know as tutoring or preparation school) was really big in Hong Kong and it carried on even when I moved to New York.” But besides the difference in the number of hours of school, Karen did not see much of a difference in school work. She did not struggle. But when I pushed for more, she told me that the one thing she probably did struggle with was finding that one friend that made her feel at ease. In Hong Kong, Karen had her family and everyone around her was Chinese so she felt like she fit in and comfortable in that setting. But she did not have that feeling of ease when she started school in America.

In elementary school, Karen was in a majority white school and there were only a handful of Chinese students. However, Karen was fortunate enough to find one Chinese friend that she could speak in Cantonese with and that made her feel at ease. After elementary school, Karen’s parents decided to transfer her over to a private school because all the zone schools in her area had a bad reputation and her parents wanted a good education for her. This was when Karen realized that she did not fit in and she did not have that one friend to make her feel at ease. Everyone at the private school had already formed their own groups and had their own friends. Karen came in mid-year so she had a bit of hard time adjusting. However, when I ask her how she felt about that struggle looking back she said, “I’m thankful.” Karen told me that she learned that she could not always rely on someone else and that she had to start forming her own bonds and stepping out of her shell.

Picture of Karen in High School with some friends

Karen eventually worked her way to being admitted into Brooklyn Technical High School where she found herself and started creating her own bonds. This is also where I met her and started our journey as close friends.

Karen and I

From her arrival in the United States, Karen embarked on her third identity as a part American. She told me that in school, she would always struggle when answering the identity question. But she realizes now that she has three identities and that she is proud of all three components of her identity. Karen may not have been through the financial struggles that other immigrants been through but her cultural background and identity is rich in a different context. She may even continue to pick up more identities in the future.

Comments