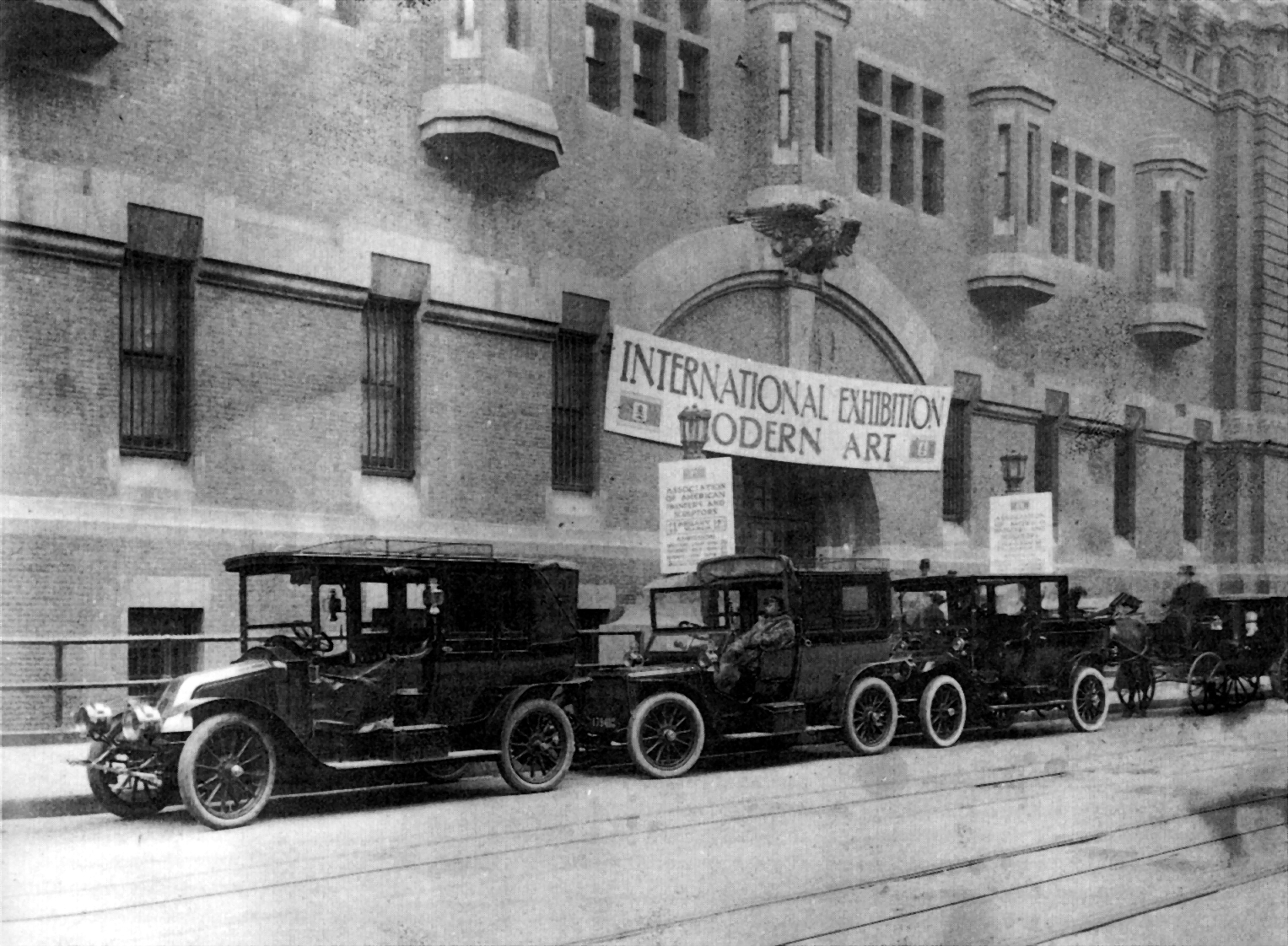

The original Armory Show was brought by the International Exhibition of Modern Art and presented at the Lexington Avenue Armory (hence the nickname “the Armory Show,” February 17th, 1913 thru March 15th, 1913; its original organizers gathered in an effort to show the progression of modern art leading up to the controversial abstract works that have become the Armory Show’s hallmark. At the time, the nation was in the midst of the end of the Progressive Era, which was a defining era of change, and, as New York was one of the capitals of the new, works of the Armory Show found inspiration through the latest movements in politics, social reform, progressive thought, developments in communication, and modern architecture.

The Armory Show at the New York Historical Society, which revisits the famous New York Armory Show of 1913, is a twenty-first century display of over one hundred works (works by Duchamp, Matisse, Picasso, Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, etc.) of one of the acclaimed avant-garde movement of twentieth-century Europe, as well as some various historical works. This particular avant-garde movement, due to its increased use of bold color and the “new” primitivized forms of the Fauves, changed the way Americans look at modern art.

Walking around the exhibition, I felt compelled to focus on the works of The AshCan School, which had its own section. The AshCan School began as a circle of realist painters centered around the artist Robert Henri; they were known for their depictions of the “raw, unvarnished” life of the city, particularly that of the working classes. Henri wanted to be a part of the exhibition only to clash with Arthur B. Davies (the principal organizer) and his supporters, worried that this European movement would overshadow the work of American artists.

These two factions represented the competing visions of modern art and its future in America, which came from late nineteenth century ideas about subject matter, focusing on urban life and pressing social problems. The new European works brought a new sense of modern being about art itself, questioning standards through experimental use of form and color.

These two factions represented the competing visions of modern art and its future in America, which came from late nineteenth century ideas about subject matter, focusing on urban life and pressing social problems. The new European works brought a new sense of modern being about art itself, questioning standards through experimental use of form and color.

One work, Circus by George Bellows, kept my attention for most of my time at the Armory Show. The painting displays a circus of some kind taking place, with the usual things one would find at a circus: animal-taming, trapeze artists, and various spectators. In this painting, however, the spectators are not regular circus-goers, but are various social classes. Looking closer, you notice seperated blacks and whites, aristocrats, middle-class, the royals, and the poor, all together in one gigantic, chaotic circus.

Adept at playing both ends of the political spectrum, Bellows seemed ambivalent about the Armory Show, though he helped organize the exhibition, noting, “The cubists are merely laying bare a principle of construction which is contained within the great works of art which have gone before.”

Brian, You do a good job of explaining the overall context of the exhibit. You then do a reading of Bellows’ painting in relation to its representation of various social groups. It is a tough thing to do to get both a reading of the formal and the social aspects of a work of art into a brief blog. The ideal is to synthesize the two. You have opted to describe the social context more than the formal aspects of the works. Very good work on this, all the same.