Homelessness in New York City: Placing the Displaced

Chris Angelidis, Rishi Dutt, Brandon Green, Vickie Savvides

Background and History:

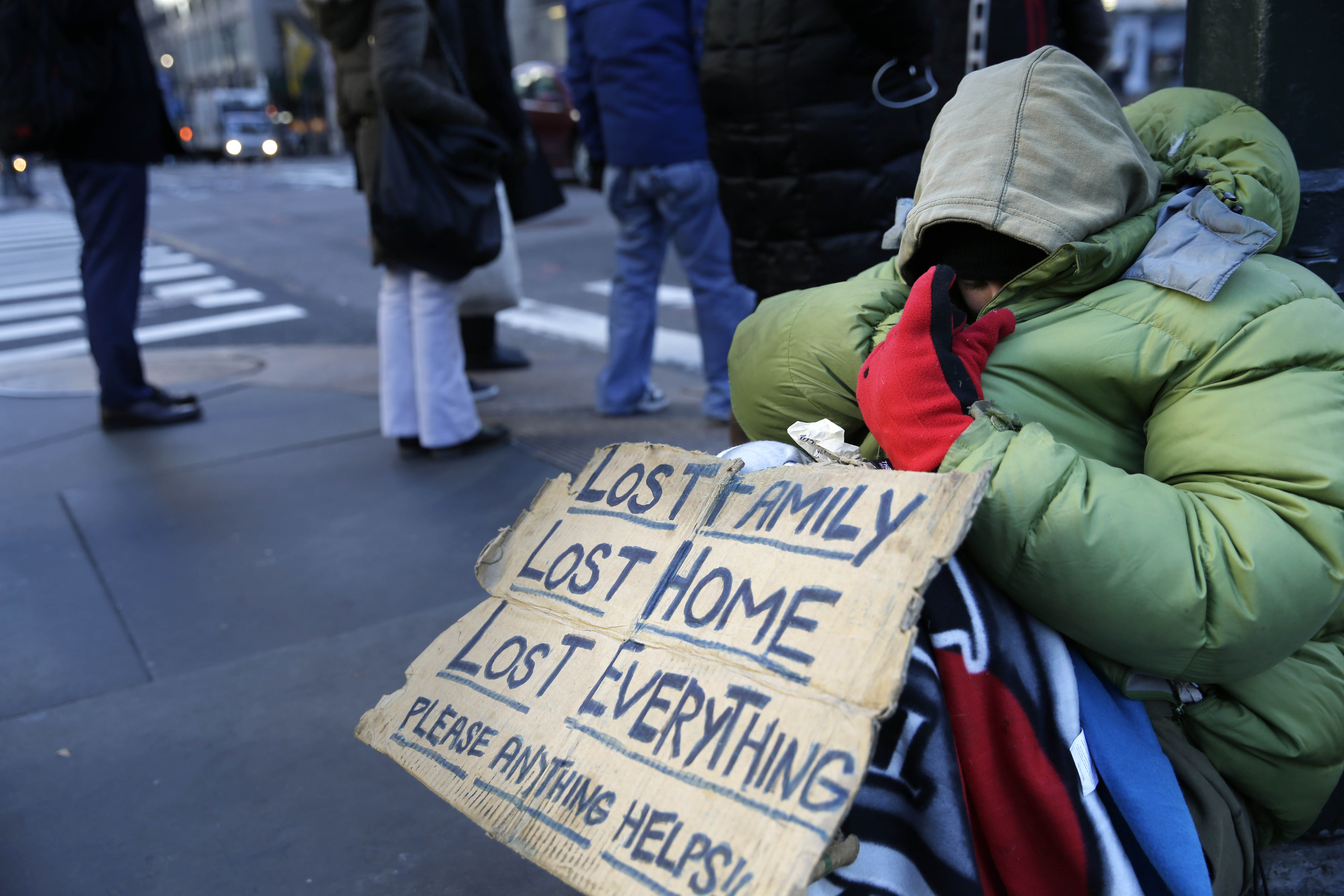

Homelessness is a worldwide social, economic, and public health concern associated with numerous behavioral and environmental risks. As published by the United Nations, an estimated 100 million persons worldwide are victims of homelessness (S12). These individuals fall into two categories: “absolute homelessness” which applies to those without any form of physical shelter and “relative homelessness” which describes the conditions of those who have physical shelter but do not meet the basic standards of health and safety.

Despite societal advancement in an age of technology and information, this “100-million-person statistic” is quite startling. In the modern-day, homelessness continues to function as both a symptom and cause of poverty and social exclusion. Most importantly though, homelessness is a threat to human rights (S12). Potential violations to the person arise from vulnerability and lack of safety that result from inadequate survivable conditions. Comprehensively, the resonating issue adversely affects international, national, and local jurisdictions. Significantly, it has impeded a universal maintenance of social welfare.

In the United States, one who is “homeless” is one who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence. As per the latest Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, “On a single night in January of 2016, 549,928 people experienced homelessness nationally” (S2). The majority of these individuals (68% of the homeless population) remained in a variety of housing projects including: emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, and/or safe havens; the remaining 32% settled in homeless shelters (S2). The way in which homeless individuals are placed into facilities is dependent on the resources that the specific locale provides, the willingness of the homeless individual to be positioned into a shelter, and the ability of the shelter to accommodate individuals within its defined capacity. Although these numbers have been published under the counts of the federal government, there are many homeless individuals who linger under the radar and may be squatting, frequently relocating, or “couch surfing.” They are known as the “hidden homeless.” Therefore, quantifying the exact number of homeless individuals is practically infeasible.

CLICK HERE FOR INTERACTIVE HOMELESS ANALYTICS MAP

The issue of homelessness is one of great salience. To be without shelter is to be deprived of basic necessities that comprise one’s being. Furthermore, to live under poor conditions accentuated by poverty and violence is debilitating. On the given night of January 2016, 34.7% of homeless individuals were substance abusers, 26.2% were mentally ill, 12.3% were victims of domestic violence, and 3.9% were persons with HIV/Aids (S1). Although the likelihood of these conditions increases due to specific living situations or lack thereof, sheltered homeless individuals are especially highly susceptible to the contraction of disease. Living with a dense crowd of people in the confines of a shelter and having limited access to healthcare systems, gives rise to a high risk of illness. Of (delete word of) the more common illnesses are HIV and the viral hepatitis B, comma needed here which affect percentages of 35% and 30% respectively (S1). Additionally, the tense, crowded environment invites abusive relations and physical anguish in which there are high counts of injury and even murder.

Within the United States, homelessness is heavily concentrated in major “COCS” or large “continuums of care.” These are primarily metropolitan hubs and large cityscapes. The reason for high concentration of the homeless in cities rather than suburbs is access to resources. Cities host mass transit systems (buses, trains, ferries) which provide transportation and potential sleep stations, programs and shelters (which offer food and temporary housing), and basic amenities (public restrooms, water fountains, etc.). Demographically, homelessness is most prevalent among white males over the age of 24; however, over one-fifth of homeless individuals are below the age of 18 (S2). These statistics have resonated since the early introduction of homelessness statistics in the 1930s. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Develop breaks homelessness into five separate categories: homeless individuals, homeless families, homeless families with children, homeless unaccompanied youth, homeless veterans and the chronically homeless, individuals who have experienced multiple episodes of homelessness within a three-year time frame. The lines that define each category are not fixed; rather, they are blurred, overlapping to account for circumstances that affect the entire population. Conclusively, the varying circumstances faced by homeless individuals add up to the same data: a threat to individual and societal function.

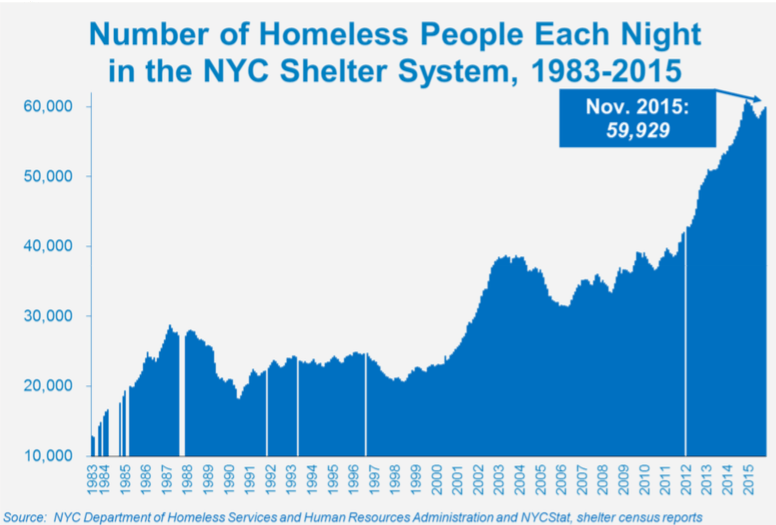

To date, the federal government has spent $4.042 billion on projects to address homelessness; however as evidenced by statistical analysis, it has failed to rectify the insurmountable national issue (S3). On scale, homelessness has successfully declined between 2015 and 2016 by approximately 3% (S2). Since the 2010 enactment of President Obama’s Opening Doors, the nation’s first strategic plan to prevent and end homelessness, the nation has seen a 14% decline in totals (S5). However, the major COCs have not experienced such positive results. In fact, many have experienced statistical increases. New York City is an example of this, experiencing some of the highest levels of homelessness since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

Obama Administration’s plan to end homelessness within 10 years

Although homelessness in New York State has declined, New York City still leads as a major city with the highest rates of homelessness nationwide (S2). In February of 2017, the Coalition for the Homeless released State of the Homeless 2017, a publication which reported a staggering 62, 535 count of homeless people sleeping in shelters in New York City (S9). This total includes 15,689 homeless families with 23,764 homeless children, sleeping each night in the New York City municipal shelter system. Of the homeless shelter population, families of at least 3 members comprise 75%. African Americans and Latino New Yorkers make up the bulk of the homeless population. The number of homeless New Yorkers sleeping each night in government shelters is now 78 percent higher than it ten years prior. Once again, however, these statistics do not account for the “hidden homeless.” The actual numbers are indicated to be as close to one standard deviation greater than provided.

New York City is the jurisdiction with the longest history of facing and dealing with homelessness. The earliest tangible documentation is the photographs of Jacob Riis during the Great Depression. A native of Denmark, Riis emigrated to the United States in the mid 19th century to focus his artwork on the homeless. The primary setting of his photographs was the New York Bowery, the city’s most impoverished neighborhood (p137- S3). With an influx of economic turmoil, sickness, and tension, New York City saw an increase in the development of homeless settlements. Nicknamed “Hoovervilles” after President Herbert Hoover, these communities crowded tents and shacks, concentrating in quarters that neighbored Central Park’s empty reservoir and Riverside Park (p139- S3). The publication How the Other Half Lives by Riis illustrates the egregious conditions undergone by homeless individuals, specifically the homeless youth.

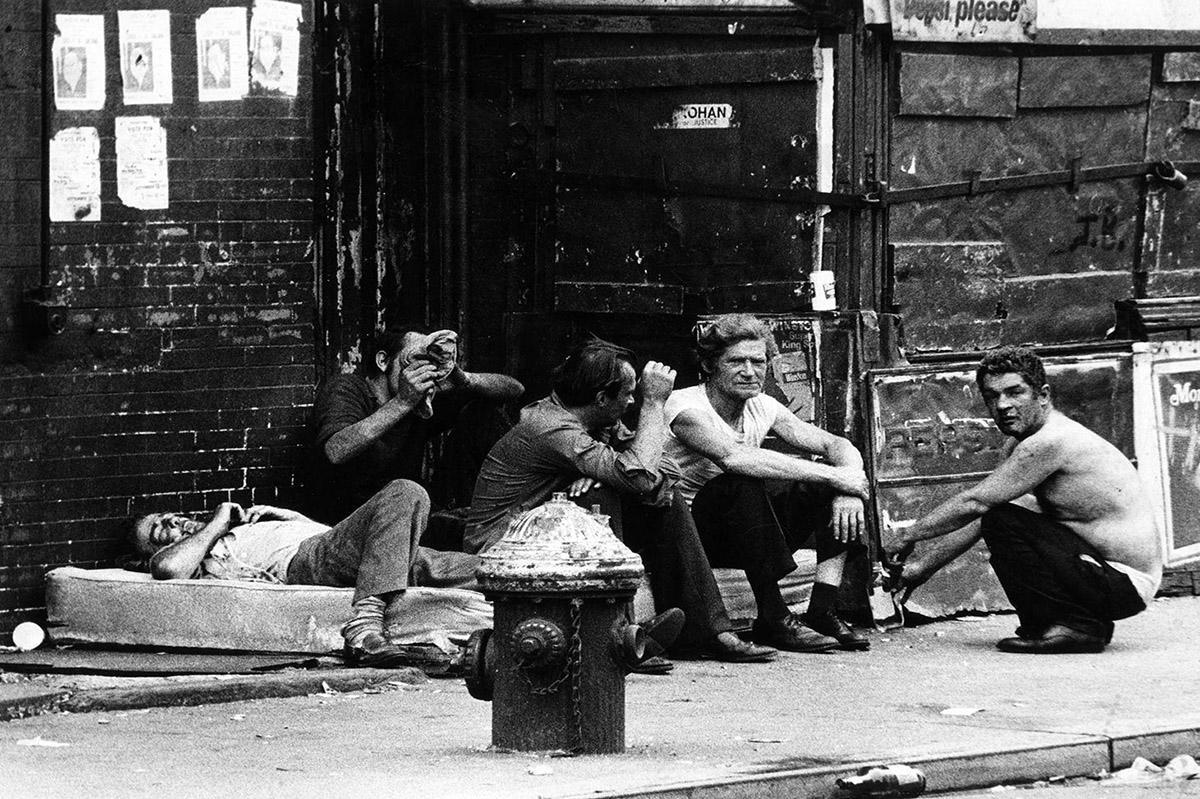

During the subsequent half century, the number of homeless individuals fluctuated due to (about) severely unstable economic conditions. In the 1960s specifically, the number of “disaffiliated alcoholics of the New York Bowery” peaked (141- S3). The largest sector of the “socially quarantined community,” as it was referred to, (comprised of) consisted of NOTE: a group consists of components, while components comprise the whole white males who were afflicted by addiction and ill health, and resorted to sleeping in streets and subways. Known as “skid rows” of the Bowery, the homeless hub was dominated by public drunkenness. Police stations sheltered homeless individuals prior to the decriminalization of public drunkenness. The concept of hotel families further developed and families who had lost their houses were located to hotels at the expense of the city.

The emergence of contemporary homelessness that exists today formally began in the 1980s. Although it is speculated that the release of mentally ill patients and increase in substance abuse due to the crack epidemic escalated homelessness throughout the city, economists such as Brendan O’Flaherty and Eric Hisch argue that the real reason for the increase in homelessness is the significant rise in income inequality (S6). More specifically, they argue that the origin of modern homelessness coincides with the impact of the widening gap on the housing market. In this case, homelessness is implied by causation rather than correlation. To further justify their findings Eric Hirsch articulates:

“When you increase income inequality, you are concentrating a lot of buying power at the top end of the system, the only unsubsidized housing construction is at the luxury end of the market and you’re not building any affordable housing at all unless it’s government subsidized. This trend which had always existed, increased due to the impending economic turmoil” (S6).

In 1981, the landmark case Callahan v. Carey established in New York a right to shelter for homeless men, women, and children. The decree set forth by this case would shape homeless policy in New York City throughout the (forthcoming )subsequent years. NOTE: forthcoming means yet to come Each subsequent mayor from Ed Koch on would enact policy to combat the overwhelming presence of homelessness. The goal to eliminate the issue is met by significant changes that unfortunately, have led to subtle results. With the lingering numbers of homelessness reaching highs even 20 years later, it is with hope the federal and state governments will finally place the displaced.

Current Events and Media Coverage:

Homelessness in New York City is a topic that perpetually receives extensive news and media coverage. This feat is due to New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s association with and constant attempts at tackling this problem. There are constant new developments and commentaries regarding the homeless population of the city. For example, within the week of April 30th, there was a plethora of articles regarding the alarming increase in homeless students in New York City. As per the city’s Independent Budget Office, during the 2015-2016 school year, “there were 32,803 homeless students…a 15 percent increase” from the previous year (S7). What is unsettling regarding this constant flood of reports seems is there are more articles discussing the difficulties of homelessness rather than the city’s plan for action to combat it.

NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio campaigning for homelessness relief

When running for the office of New York City Mayor in 2013, Bill de Blasio promised to fight homelessness. He wanted to successfully tackle a problem that has affected New York City for multiple decades. It is with these promises that he edged out his opponent and garnered substantial support to become the next mayor of NYC, which meant he had to turn his words into action. Among these supporters was the Coalition for the Homeless, who upon de Blasio’s victory of the election, lauded him for his “knowledge and experience to tackle NYC’s homelessness crisis” (S9). They genuinely believed in de Blasio’s message and his cause, and put out several press releases and statements to the media asserting their full support of the Mayor-elect:

Indeed, we are very encouraged to see that de Blasio’s campaign platform calls for resuming priority referrals of homeless families to Federal housing programs like public housing. It’s also good news to see that the platform calls for eliminating many of the bureaucratic barriers that have wrongfully denied shelter to many vulnerable children and families. (S9)

With such a venerable organization backing the Mayor-elect, Bill de Blasio positive publicity increased. He was referred to as the candidate who would successfully push back against homelessness in the city. One of his most popular anecdotes on the campaign trail was the “tale of two cities,” in which he discussed that New York City is not all the glitz and glamor of Times Square and Fifth Avenue. Within the city is a sect that encompasses “the more than 52,000 homeless New Yorkers – among them 22,000 homeless children – who are sleeping each night in municipal shelters” (S9). This statement was a controversial yet effective talking point for de Blasio, who earned positive and optimistic press, but also garnered criticism. Negative media referred to him as “foolish” for making such an overbearing promise.

Flash forward to present-day, and the headlines have decisively shifted from “What will Mayor de Blasio do?” to “What has Mayor de Blasio really done?” The common sentiment seems to be that de Blasio reneged on his campaign promise of battling hard against homelessness in NYC. He is ascribed with taking what critics believe is the “easy route” and opening new homeless shelters. In fact, in 2015, Mayor de Blasio halted the opening of new homeless shelters in New York City because he believed it was an ineffective method of dealing with homelessness. This spurred news reports on both spectrums, hailing his realization of a failed effort but also criticizing his decisions to open them in the first place. However, within the past two months, de Blasio announced a plan to open 90 more shelters over the next five years. Doing so is essential to curbing the boom of the homeless population during his tenure in office. With his re-election approaching, many believe that this reinstatement of opening new homeless shelters is merely to gain political points, rather than not do anything at all: “The calculation is that inaction would be even more damaging. Mr. de Blasio staked his political identity on aiding New York City’s less fortunate, and has been attacked by critics as an ineffectual manager. His critics had already seized on the issue, which has grown more visible on city streets” (S10)

Homelessness has increased under Bill de Blasio’s tenure

Most new press coverage of the current situation regarding the homeless population in NYC portrays the mayor’s actions with a negative connotation, discussing his inability to curb homelessness growth as he promised in his campaign platform. According to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (USHUD), the homeless population in New York City has increased from approximately 53,000 when Bill de Blasio assumed office, to over 60,000 today. This has contributed to the wide discontent and dissatisfaction with Mayor de Blasio’s handling of the homeless problem in the city. It functions as a main reason for why he faces political pressure in his upcoming reelection bid. His struggles are widely reported, including his run-in with the law, all of which is not creating a positive outlook for a second term as mayor. Facing increasing pressure from not only his constituents but from Albany and the federal government, de Blasio felt he needed to do something to reaffirm his commitment to providing assistance to the homeless. Unfortunately, this decision came in the form of opening new and expanding current homeless shelters, a solution which only drags out the problem, rather than attack the reason why people become homeless in the first place.

Policy:

Historically, New York City has addressed homelessness with a mix of three strategies: entitlement, paternalism, and post paternalism (p5- S3).

The entitlement ideology is based on the fundamental belief that all people have a natural right to shelter(p5- S3). It is up to the government to provide it for those who cannot provide it for themselves. This was the primary policy towards homelessness during the 80’s. During the late 70’s, advocacy groups such as Coalition for the Homeless emerged. They pushed for this policy of entitlement to address the few and decrepit homeless shelters that were concentrated in Bowery. Conditions were so bad that many homeless preferred sleeping on the streets to the violence, disease, and drug use that came with staying at one (p16- S3). Through the efforts of these groups, the Callahan Consent Decree was signed stating that the city has a duty to provide shelter to the homeless who are of “physical, mental or social dysfunction” or meet the standards of the home relief program in New York State (p24- S3). Moreover, the housing to be provided had to meet a series of quality requirements. Such standards included a staff to resident ratio, hours of regular operation, first aid requirements, and cleanliness standards. This did well to better the standards of shelters and to encourage the homeless to stay off the streets at night.

Homeless men on the streets of Bowery in the 70’s

At first, the city lived up to this obligation by converting abandoned schools, asylums, and armories into shelters. Interestingly enough, the housing standards created in the Callahan Decree made it difficult for the city to optimize its shelter building. A lot of the ratios were created without proper research prior and as such, the city had to spend its money inefficiently to meet those standards. This diverted funds that could have otherwise been used to create more comfortable units.

The paternalism ideology is characterized by a sense of conditional entitlement to shelter(p6- S3). This was the primary policy towards homelessness during the 90’s. Those who behaved well earned a right to the housing while those who didn’t were excluded. The policy emerged as a response to the shortcomings of shelters and housing under entitlement. It was driven by a transition from government run shelters to privatized shelters. This switch created a remarkable increase in shelter quality and effectiveness. Those who stayed in shelters were motivated and actively sought for work and betterment. They did not want to be out on the streets.

Since the government was not in charge of overseeing operations, facilities could implement a strict set of rules. Primarily these rules would be geared towards stopping violence and drug use as well as keeping the residents looking well kept (p111- S3). These shelters featured programs and activities meant to train the homeless with skills that could get them a permanent job elsewhere. Social workers would help locals develop betterment plans and help them get back on their feet. Because of the stricter standards, those seeking betterment would end up in private shelters while those who were more delinquent would remain in the city shelters. This created a two tier system of shelters, and left the city shelters more dangerous than ever before. Moreover, the city was doing nothing to help residents get permanent housing. As such, paternalism can be viewed as a policy geared at managing but not eliminating homelessness.

The inside of a homeless shelter

The post paternalism ideology is characterized by trying to end homelessness completely rather than just treating it (p8- S3). It is driven through the idea of supportive housing– providing subsidized housing for at risk people in order to keep them off the streets. This has been the primary policy towards homelessness in the 2000’s. With a “housing first” approach, it tries to get the homeless relocated into permanent housing units and then to address their problems (p147- S3). Keeping people in their own homes and off the streets has been found to be the most effective way (at) of combating homelessness. Furthermore, it relieves some of the stress from the congested shelter system, improving the quality of its service. While ending homelessness is a great goal, it has proven almost impossible so far.

Today’s policy for addressing homelessness has been heavily influenced by the previously mentioned ideologies. According to the Department of Homeless Services, strategy can be divided into three parts: prevention, shelter, and permanence (S8). Prevention focuses on people at risk of losing their homes, shelter focuses on people already homeless, and permanence focuses on transitioning the homeless into permanent residences. The combination of these three strategies addresses the shortcomings of previous approaches.

It is impossible to end homelessness if new people are still losing their homes. Prior policies were geared at providing shelter for those already homeless, but they did little to stem evictions. According to the 2016, Mayor’s Management Report, 19,139 single adults are newly entering the shelter system each year (p195- S3). By approaching the problem at its roots—people who are losing their homes—instead of merely addressing the symptoms, the city has a shot at reducing the number of the homeless to a manageable amount. The current shelter system is very overburdened. Research estimates that it costs the city $34,518 to house an individual in a shelter per year (p196- S11). That money would be better spent towards rent assistance, keeping people off the streets in the first place. This could help end the vicious cycle that occurs once on the streets. By doing so, the city would actually be saving money. Moreover, by stemming the flow of people into homelessness, the city has more resources to put towards those who are already homeless.

Prevention services in NYC are run by the Homebase program. It provides services to protect against eviction, assist in obtaining public benefits, provide rent assistance, education and job placement assistance, financial counseling, help relocating, and short term financial assistance (S8). A good way to look at this program is as a time buffer that allows those at risk of homelessness to get back on their feet before ending up on the streets. It has been shown to reduce shelter applications by 49% (S8) 27.

There are approximately 127,652 unique individuals who used New York City shelters in 2016 (S4) . Getting them into a home is not something that can happen overnight. As such, the city has found an immense need for a shelter system, to provide temporary housing to those in need. In properly run establishments, it protects against the crime and struggles that are found on the streets. These systems keep the homeless safe and are the first step towards recovery. In a city as cold as NYC, they are a crucial part in keeping the homeless healthy during the winter. Many feature counseling programs and training that are geared towards giving the displaced the base from which to grow. Furthermore, they expect capable adults to actively look for work in exchange for staying in the shelter (S8).

Alternative Solution:

The proposed solution of utilizing supportive housing as shelter has been shown to be an effective method of combating homelessness, as per the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness:

Supportive housing has been shown to help people with disabilities permanently stay out of homelessness, improve their health conditions, and lower public costs by reducing their use of crisis services. In fact, numerous studies have shown that it is cheaper to provide people experiencing chronic homelessness with supportive housing than have them remain homeless. (S5)

According to this agency, by implementing and expanding supportive housing, chronic homelessness has been reduced by 27% between 2010 and 2016. Although this is a step in the right direction, it means that if enough resources are dedicated towards this plan, amongst federal, state, and local governments, this solution has the potential to make a real dent in New York City’s homeless population.

Decrease in homelessness spurred by supportive shelters

The problem that currently exists with employing shelters as a solution to homelessness is that it does not tackle the root of the problem. When a homeless shelter is opened, there is a misconception that this is directly combating homelessness. In reality, all it is doing is elongating the process. Of course, opening a shelter for the homeless offers benefits, providing a place to sleep at night, food, water, and other resources. However, besides offering sustenance, what more does a shelter really provide? It does not allow a struggling family to get back on its feet, nor does it bode well that shelters tend to be crime-ridden and their conditions rapidly deteriorate. Politicians and government officials tend to use shelters as the end all, be all in terms of their fight against homelessness, which is likely why this issue has persisted in New York City from administration to administration. This is also why NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio faces such backlash to his proposal of opening 90 more homeless shelters in the next five years. He can open as many shelters as he wants, which can assist the existing homeless population, but in and of itself, will do nothing to stop the influx of new people into homelessness, nor will it allow currently homeless people to escape this cycle. Conclusively, it will be nearly impossible to work towards combating and ending homelessness.

Koch’s ten year housing plan looked to address many of the issues created by the Callahan Decree. It did so by raising money through bonds sold to private investors to convert vacant city owned properties into permanent housing units (p52- S3). This marked an important step at addressing the homelessness problem and not just getting them off the streets. It was giving the people the standard of living that an impoverished family could expect. Perhaps its most remarkable achievement was keeping families out of shelters. This had a ripple effect which can be seen across generations. Unfortunately, this had the negative effect of incentivizing impoverished families to declare bankruptcy and become homeless in order to get access to state subsidized apartments (p80- S3).

The New York City plan for housing and assisting homeless adults sought to overcome the problems facing single adults in overcrowded shelters (p90- S3). It aimed at creating smaller shelters that were scattered across the city as opposed to large ones. This would make them safer and easier to maintain. The second part of the plan was to provide them with training to reintegrate them into society. This plan looked to not only treat the symptom, but address the very problems that made people homeless in the first place.

Providing shelter alone will not get shelter residents back on their feet. Instead, the city has adopted permanence programs, which find them permanent housing options. Prior policies neglected the temporary element of these shelters. They would view these programs as a long term solution; however, such an outlook is not sustainable. It is easier once inside a home to get back into a positive routine. Instead of searching for a place to sleep at night, people have more time to look for work and to gain skills which could help transition them back into the regular economy.

NYC’s homeless population has skyrocketed in recent years

Thus, in order for supportive housing and shelters to be effective at all, they must work in conjunction with other aspects. To focus on the goal of permanence, a proposed solution is to create and implement a job works program in order to train the homeless with the vocational skills necessary to get on their feet and go out and try and secure employment. According to the same United States Agency, “one of the most effective ways to support individuals as they move out of homelessness and into permanent housing is increasing access to meaningful and sustainable job training and employment” (S5). The leading legislation working towards this cause is titled the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), which was signed into law by Former President Barack Obama in 2014, after it decisively passed both chambers of Congress with only a handful of those opposing the bill. This law is aimed directly at targeting homelessness, how to combat homelessness by creating employment opportunities for the homeless and veterans, and reviewing federal policies and regulations regarding works programs. If New York City can institute a similar employment opportunity-centered plan such as this federal law, it will allow the homeless living in shelters to find a foothold and attempt to propel themselves out of their situation.

One of the current barriers faced in securing employment opportunities for the homeless is that there is a negative stigma surrounding them which is why employers are reluctant to or merely flat out deny hiring workers who live in a shelter. According to research conducted by the National Alliance to End Homelessness, “a study by the Chronic Homelessness Employment Technical Assistance Center (CHETA) found that provider staff members are ‘frequently challenged by pervasive negative stereotypes when approaching employers about hiring qualified homeless job seekers’”(S8). In order for this plan to work, employers need to be given incentives, whether it’s in the form of tax breaks or tax deductions, similar to those that developers receive when designating units in a building dedicated to be affordable housing. Living status should not be a factor that affects an individual’s application status, unless it is directly hindering their ability to work efficiently, productively, and punctually. As long as an individual can carry out the tasks bestowed upon him by an employer, he/she should not be discriminated against in any manner, which is the notion that employers need to be persuaded of.

With the efficient and successful implementation of the three aspects to this solution, prevention, shelter, and permanence, this plan will surely leave an impression on homelessness in New York City. Whether that impression is largely positive or negative, and the extent to which this plan is effective, principally depends on the government’s willingness and dedication to the problem, but also relies on collaboration between different levels of government, employers, landlords, and the homeless themselves. In theory, this solution sounds impeccable. On one end, preventative measures are instituted in order to prevent more and more New York City residents from losing their homes, to stymie the growth of the homeless population. On the other hand, providing supportive shelter to those who are already homeless provides them with the bearing and daily support they need to survive. Once they get their feet on solid ground, the permanence programs assist them with returning to normal life, either through the development of vocational skills or job placement. Working in conjunction, these three aspects seemingly solve the problem that has eluded NYC for decades. However, this is definitely not a one-man battle, as demonstrated by its persistent nature, but if all parties involved come together at a mutual agreement, there is the potential to finally shed New York City of the notorious honor of encompassing the most homeless people in the United States.

Time to solve NYC’s homeless problem

Works Cited

Badiaga, Sekene, Didier Raoult, and Philippe Brouqui. “Preventing and Controlling Emerging and Reemerging Transmissible Diseases in the Homeless (Statistical Analysis of Disease).” National Center for Biotechnology Information. US National Library of Medicine, 14 Sept. 2008. Web. <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2603102/>. (S1)

Henry, Meghan, Rian Watt, Lily Rosenthaal, and Azim Shivji. “2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress.” Office of Community Planning and Development. The United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, Nov. 2016. Web. <https://www.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2016-AHAR-Part-1.pdf>. (S2)

Main, Thomas James. Homelessness in New York City: Policymaking from Koch to De Blasio. New York: New York U, 2016. Print. (S3)

“New York City Homelessness: The Basic Facts.” NYC Homelessness. Coalition for the Homeless, Apr. 2017. Web. <http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NYCHomelessnessFactSheet_2-2017_citations.pdf+>. (S4)

Obama, President Barack. “Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent Homelessness.” Https://www.usich.gov/. United States Interagency on Homelessness, June 2015. Web. <https://www.usich.gov/resources/uploads/asset_library/USICH_OpeningDoors_Amendment2015_FINAL.pdf>. (S5)

O’Flaherty, Brendan. Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1998. Web. (S6)

Press, Associated. “NYC Has Increase in Homeless Students.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 25 Apr. 2017. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2017/04/25/us/ap-us-homeless-students-nyc.html?_r=0>. (S7)

“Prevention.” New York City Department of Homeless Services. NYC.gov, 2004. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <http://www1.nyc.gov/site/dhs/prevention/prevention.page>. (S8)

Routhier, Giselle. “State of the Homeless 2017 Rejecting Low Expectations: Housing Is the Answer.” (n.d.): n. pag. Coalition for the Homeless, Mar. 2017. Web. <http://www.coalitionforthehomeless.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/State-of-the-Homeless-2017.pdf>. (S9)

Stewart, Nikita, William Neuman, and J. David Goodman. “Adding Homeless Shelters Is a Political Risk, but De Blasio Sees No Alternative.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 26 Mar. 2017. Web. 30 Apr. 2017. <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/26/nyregion/new-york-city-homeless-shelters-de-blasio.html>. (S10)

Tarlow, Mindy, Bill De Blasio, and Anthony Shorris. “Mayor’s Management Report.” Nyc.gov. New York City Government, 2016. Web. <http://www1.nyc.gov/assets/operations/downloads/pdf/mmr2016/2016_mmr.pdf+>. (S11)

“United Nations.” Human Rights Council. United Nations General Assembly, 18 Jan. 2017. Web. <https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/009/56/PDF/G1700956.pdf?OpenElement>. (S12)