The Jewish New Year, most well known as Rosh Hashanah, is celebrated as the “head of the Jewish year” as many people refer to it. Like many other Jewish holidays, Rosh Hashanah is celebrated for two days, beginning at sundown and ending at nightfall two days later. Although it is called the “head of the year” and known as the Jewish new year, ironically the holiday actually falls on the first two days of Tishrei, the 7th month of the Jewish calendar, which typically falls sometime during either September or October. Rosh Hashanah celebrates the creation of the world and marks the beginning of the Days of Awe, a 10-day period of introspection and repentance that culminates in Yom Kippur, which is the Jewish holiday of atonement. It is a day of prayer, a time for the Jewish people to ask for a year of peace, prosperity and blessing. It is also a joyous day when the Jews proclaim God as the King of the Universe. The Jews are taught that the continued existence of the universe depends on God’s desire for a world, a desire that is renewed when the Jews accept His kingship anew each year on Rosh Hashanah.

The verse in the Torah which is the source for the origins of Rosh Hashanah

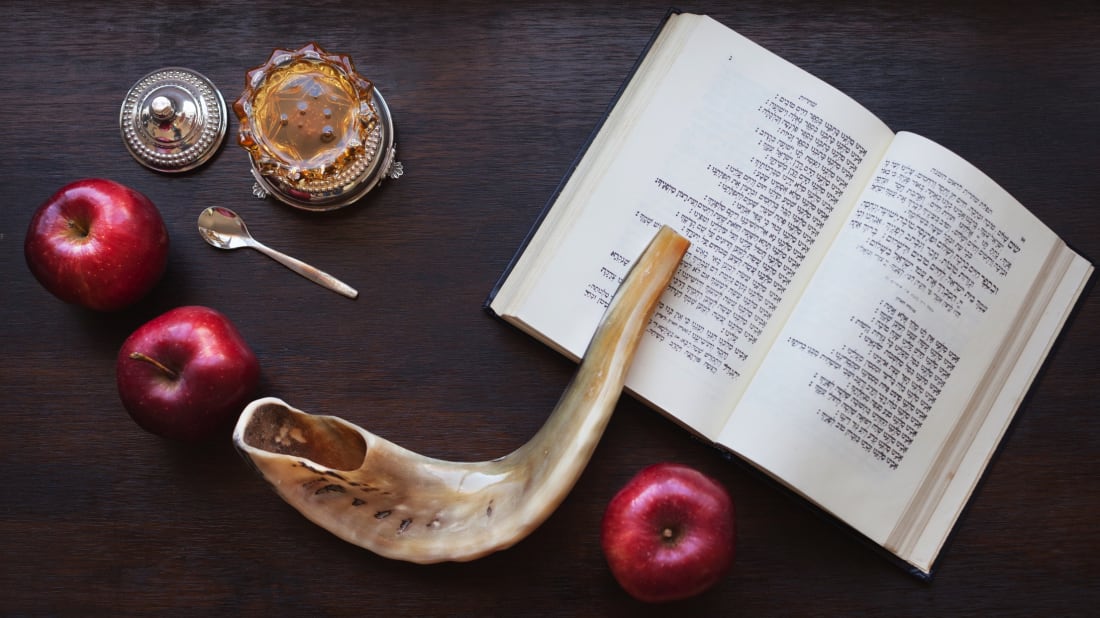

The term “Rosh Hashanah” isn’t written explicitly in the old testament, but instead appears under different names with many traditions mentioned like the blowing of the shofar, which is a ram’s horn. The Torah, the written teachings of Judaism, does not explicitly refer to the day as “Rosh Hashanah”. Rather, in Leviticus 23:24 it writes, “Speak to the children of Israel, saying: In the seventh month, on the first of the month, it shall be a Sabbath for you, a remembrance of [Israel through] the shofar blast a holy occasion.” The Rabbis learned out from this verse that it refers to making the beginning of the new year. The Mishnah, the oral teachings of Judaism, believes that there are four new years in Judaism. The four new years are: on the first of Nissan, the new year for the kings and for the festivals; on the first of Elul, the new year for the tithing of animals; on the first of Tishrei, the new year for years, for the Sabbatical years and for the Jubilee years and for the planting and for the vegetables; on the first of Shevat, the new year for the trees. Although there are arguments for when the other new years occur, it is agreed upon that the first of Tishrei refers to the new year for years. The old testament refers to this day as Yom Teruah, which means day of Shofar blowing. In Jewish prayers, the holiday is often called Yom Hazikaron, which means day of remembrance and Yom Hadin, which means day of judgement since this is the day when G‑d determines the fates of everyone for the year ahead.

The blowing of the shofar at the Western Wall

The Jewish calendar begins with the month of Nisan, but Rosh Hashanah occurs at the start of the 7th month known as Tishrei because this is when God is said to have created the world. For this reason, Rosh Hashanah can be seen as the birthday of the world rather than New Year’s in the modern sense, but Rosh Hashanah still marks the beginning of a new year with the number of the calendar year increasing on this day. On this day, God judges all beings during the 10 Days of Awe, deciding their fate, in other words whether they will live or die, for the new year. Jewish law teaches that God inscribes the names of the righteous in the ‘book of life’ for the following year and condemns the wicked to death on Rosh Hashanah. People who fall between the two fates have until Yom Kippur to perform teshuvah, which means repentance, to change their inscribing. As a result, religious Jews often view Rosh Hashanah and the days surrounding it as a time for prayer, good deeds, reflection and forgiveness.

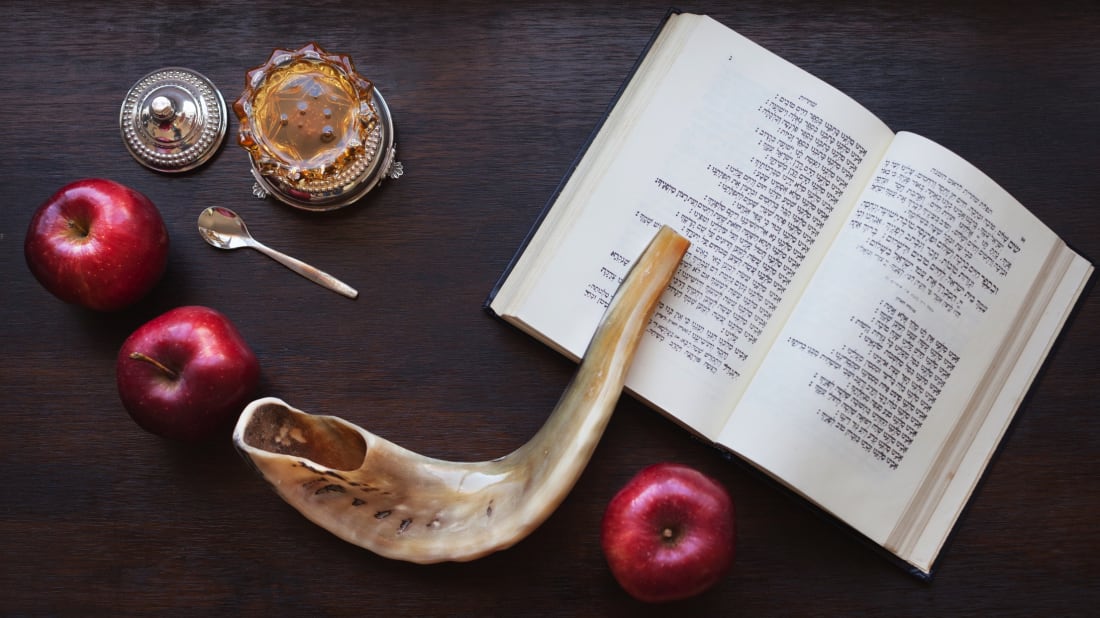

Unlike traditional New Year’s celebrations, which oftentimes end up becoming huge parties, Rosh Hashanah is more of a respectful and reflective holiday. Jews won’t go to work and most Jews will spend the larger part of their day attending synagogue. Since the prayer services of Rosh Hashanah include distinct liturgical texts, songs and customs, congregations read from a special prayer called a machzor during both Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

The Machzor opened to a special prayer recited on Rosh Hashanah

Since the Jews are obviously not partying during this holiday, they most likely are observing the holiday with and its traditions. Many traditions of the holiday include;

- Hearing the sounding of the ram’s horn (shofar) on both mornings

- Beginning in Elul, the month prior to Tishrei, a ram’s horn is blown daily, announcing the coming of the High Holidays. This blowing is meant to wake the listener up in hopes of them performing repentance. The ram’s horn, which is called a Shofar, makes a trumpet-like sound and is a major symbol of the holiday. On the day of Rosh Hashanah itself, a special pattern of blowings is performed consisting of tekiah, a long blast; shevarim, three short blasts; teruah, nine quick blasts; and tekiah gedolah, blown for as long as the blower is able to. Due to this ritual’s close association to the day, the holiday is also known as Yom Teruah, the day of the sounding of the shofar.

- Eating festive meals with sweet delicacies during the night and day, which include:

-

- Kiddush over wine or grape juice

- A major component of Jewish holidays is sanctifying the meal by performing a blessing over a cup of wine to begin the meal. This is meant to emphasize the importance of the meal by turning it into a meal which would be fit for kings, since the Jewish people are supposed to view themselves as royalty on holidays.

-

The ceremonial cup that is used for Kiddush

- Round, raisin challah bread dipped in honey

- The roundness of the challah is meant to symbolize the cyclical nature of life. Even when not performing services, the Jewish people are still meant to reflect and recognize the importance of the upcoming year and their need to perform repentance in order to be inscribed into the book of life. Some believe that the shape of the bread is meant to symbolize the crown of God, another way of viewing themselves as royalty during the meal. Both the raisins and honey are meant to symbolize the sweetness of life, representing the wanting of a sweet life for the upcoming year.

-

Challah with raisins baked into the bread

- Apples dipped in honey (on the first night)

- In ancient times, Jews believed that apples contained healing properties, and that the eating of them on the first night of Rosh Hashanah would symbolize their good health for the upcoming year. Today, most people recognize the apples dipped in honey as a staple of the holiday, yet eat them more as a symbolic nature, rather than a medicinal one. The honey is used to sweeten the fruit, symbolizing the sweet new year that the Jews are praying for.

Apples and Honey, a popular Rosh Hashanah food pairing

-

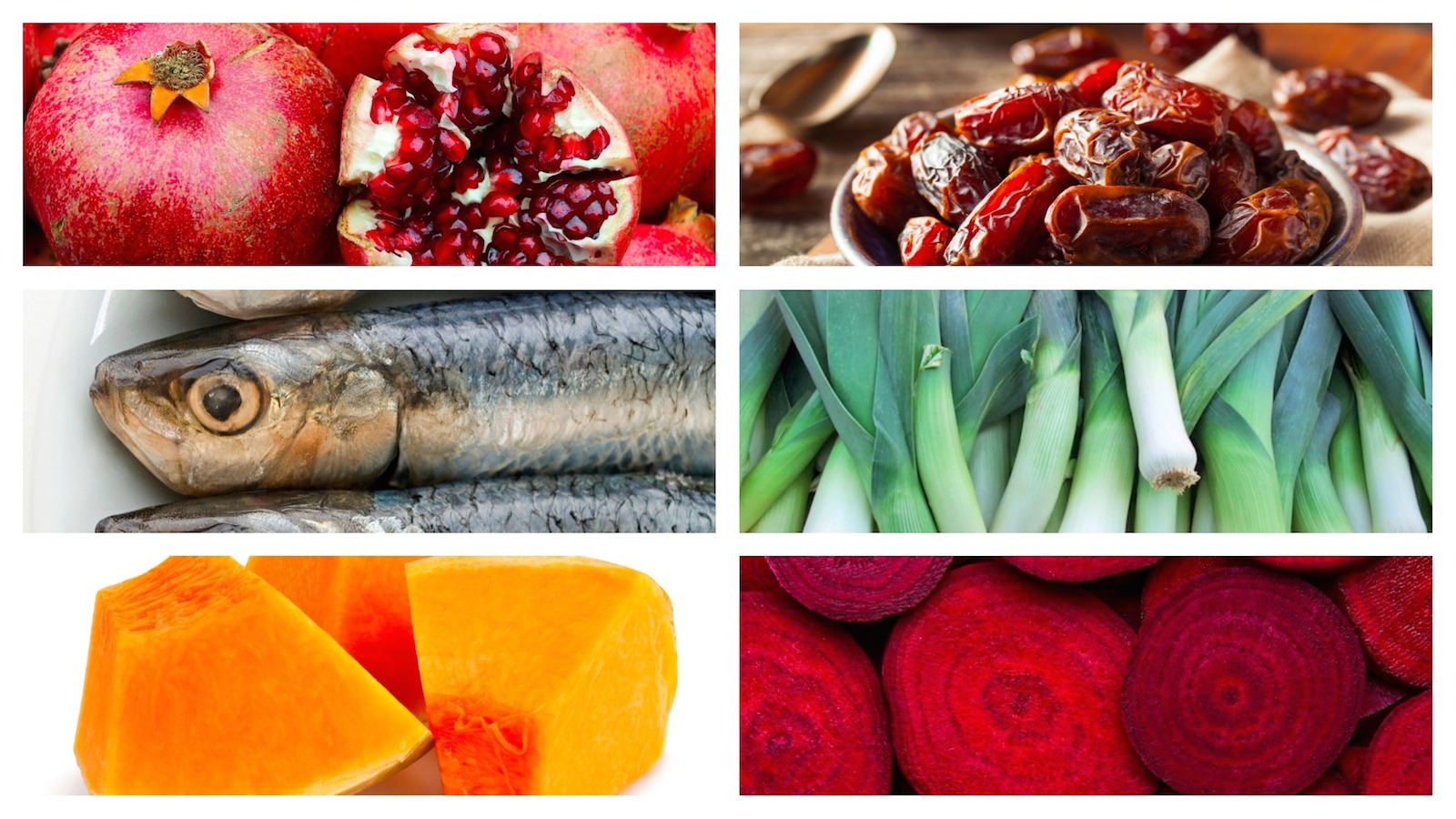

- The head of a fish

- It is common to place a head of a fish on the meal’s table, symbolizing the head of the year. It is meant to serve as a reminder for the beginning of the new year.

- Pomegranates

- It is believed that all pomegranates contain 613 seeds, which is the same number of mitzvot (commandments) that the Jewish people have. The pomegranates are eaten to symbolize the desire to consume all of the mitzvot in the following year.

-

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/pomegranate-fruit-on-cut-board-157685468-588901525f9b5874ee801d3e.jpg)

Pomegranates also possess many nutrients which are beneficial to one’s health

- A new fruit on the second night

- One is supposed to eat a fruit that they have not eaten within a calendar year. Before its consumption, the blessing of shehechiyanu is recited on both the day and the fruit. The blessing is recited whenever an act or food is consumed for the first time within a year. Although the blessing is recited on the food, it covers the entire holiday and actions performed as well.

- Performing Tashlich, a brief prayer said at a body of freshwater

- Some Jews have the practice of throwing pieces of bread into a body of freshwater. The bread is supposed to symbolize the sins of the past year, and they are being thrown away. This is supposed to help produce a spiritually cleansed and renewed person.

Congregants performing Tashlich

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/pomegranate-fruit-on-cut-board-157685468-588901525f9b5874ee801d3e.jpg)