Rowling has a tendency to introduce characters as either good or evil, then gradually reveal over the course of the series how they actually embody some combination or middle ground between the two. For most of the series, however, Harry stubbornly refuses to recognize anything beyond the two extremes.

After Harry learns about Dumbledore’s past, as discussed above, Hermione vainly attempts to convince him not to see Dumbledore as completely evil. She reminds him of the heroic Dumbledore they knew and tries to make Harry understand that, “He changed, Harry, he changed! It’s as simple as that! Maybe he did those things when he was seventeen, but the whole of the rest of his life was devoted to fighting the Dark Arts!” (DH 361). Despite Hermione’s logic, Harry can’t help but adamantly insist he’s been betrayed. According to his understanding of morality, if Dumbledore wasn’t all good, he must have been all evil. Trapped in this all-or-nothing mentality, Harry takes it far too personally when Dumbledore’s immoral past is revealed. He later questions whether everything Dumbledore ever told him was a lie.

Harry feels similar anguish each time a character proves to be more than he or she seems. He is devastated when he discovers his father, who he idolizes as a martyr and about whom he has never heard anything but praise, was a bully as a teenager. Harry feels “horrified and unhappy,” (OotP 650) and “as though the memory of it was eating him from inside” (OotP 653). He even goes as far as wondering whether his father had forced his mother to marry him. He can’t accept the idea of his father as anything other than completely good or completely evil. “For nearly five years the thought of his father had been a source of comfort, of inspiration. Whenever someone had told him he was like James, he had glowed with pride inside. And now… now he felt cold and miserable at the thought of him” (OotP 653-654).

After Sirius dies, and Dumbledore reveals his mistreatment of the house-elf was the cause, Harry is furious at Dumbledore for his implicit criticism of Sirius. “The rage that had subsided briefly flared in him again…He was on his feet again, furious, ready to fly at Dumbledore, who had plainly not understood Sirius at all, how brave he was, how much he had suffered…” (OotP 832). For Harry, Sirius’s final sacrifice means he could never have been anything but completely good. It’s impossible for Harry to reconcile Sirius’s good and bad traits; he can only see his godfather, like his father and Dumbledore, as one or the other.

Harry also fails to understand that not everyone shares this dualistic worldview. When Dumbledore acknowledges Sirius’s moral failings, Harry immediately accuses him of implying that Sirius deserved to die for his flaws. Dumbledore, of course, believes nothing of the sort. In fact, he is “ever on guard against letting his perception be clouded by labels, prejudicial stigmas, and pigeon holes” but he also knows Harry is not yet capable of accepting this type of non-binary morality (Granger, Keys 195).

Of course, Harry’s apocalyptic sense of morality not only prevents his acceptance of bad traits in good characters, it blinds him to any redeeming characteristics in so-called “evil” characters. Harry hates his Muggle relatives, not without good reason. They neglected and abused him as a child, locked him in a cupboard under the stairs and forced him to do all the housework. The second Dumbledore starts to say something positive about his aunt, Harry interrupts, “’She doesn’t love me,’ said Harry at once. ‘She doesn’t give a damn -‘ ‘But she took you,’ Dumbledore cut across him. ‘She may have taken you grudgingly, furiously, unwillingly, bitterly, yet still she took you” (OotP 835-836). This time, Dumbledore doesn’t let Harry get away with using her faults to eliminate her virtue. Obviously Dumbledore doesn’t think she was a good surrogate parent. But he also refuses to condemn her as evil within a binary moral system.

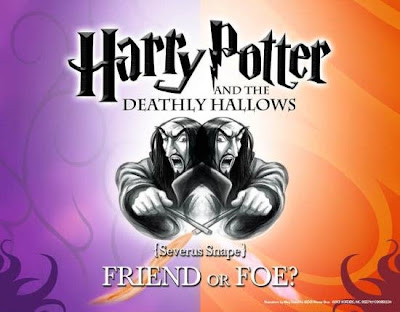

Severus Snape, Harry’s Potions professor, seems to hate Harry on sight, and the feeling quickly becomes mutual. At eleven years old, Harry decides that because Snape picks on him for (apparently) no good reason, he must be evil. For the following six books, nothing can convince him Snape is actually working to protect him. Harry suspects Snape of helping Voldemort in every scheme, even after Dumbledore repeatedly assures him that he trusts Snape completely. Harry doesn’t understand the moral gymnastics required for Snape to put on a convincing show as a double agent. Spying for Dumbledore within Voldemort’s inner circle means maintaining his cover, at all costs. Displaying anything less than hatred of Harry could raise Voldemort’s suspicion. In Harry’s eyes, however, Snape must be as evil as his actions.

Severus Snape, Harry’s Potions professor, seems to hate Harry on sight, and the feeling quickly becomes mutual. At eleven years old, Harry decides that because Snape picks on him for (apparently) no good reason, he must be evil. For the following six books, nothing can convince him Snape is actually working to protect him. Harry suspects Snape of helping Voldemort in every scheme, even after Dumbledore repeatedly assures him that he trusts Snape completely. Harry doesn’t understand the moral gymnastics required for Snape to put on a convincing show as a double agent. Spying for Dumbledore within Voldemort’s inner circle means maintaining his cover, at all costs. Displaying anything less than hatred of Harry could raise Voldemort’s suspicion. In Harry’s eyes, however, Snape must be as evil as his actions.

After Sirius’s death, Harry uses his righteous certainty of Snape’s guilt to deny his own. He demands Dumbledore give him a good explanation for Snape’s behavior. After getting one, “Harry disregarded this; he felt a savage pleasure in blaming Snape, it seemed to be easing his own sense of dreadful guilt” (OotP 833). Even though it comes at the cost of powerful allies like Snape and Dumbledore, seeing the world in black and white makes Harry’s life far simpler and his emotions easier for him to handle. It isn’t until the very end of the series that Harry finally matures enough to lose this crutch and appreciate shades of grey.

The conversation quoted at the beginning of this section, which Harry has with Dumbledore just before the final battle, sets in motion the events that prove Harry’s move beyond binary morality. Harry’s eventual acceptance of Snape’s true loyalty and Dumbledore’s transformation from devil to god to neither one nor the other would have impossible within a binary framework. The fact that Snape could be Harry’s ally and that Dumbledore could embody all three of those identities forces readers to consider “very complex and shaded questions that the entity now poses about the nature of evil…” (Rosen 17). By inviting the reader to share Harry’s transcendence of the apocalyptic moral paradigm, Rowling “satisfies the need we all feel for meaning that is not moralizing and for virtue that is heroic and uniting rather than divisive” (Granger, Keys 236).

According to Rosen, this transcendence functions as the New Jerusalem of the story. New Jerusalem, as canonically described in the Book of Revelation, is literally a “great city, the holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God” (Revelation 21:10). It is a gift from God to the faithful followers that finalizes the div apocalyptic ision between the saved and the damned. In contrast, in postmodern narratives, “New Jerusalem is less a place than a new way of seeing: a new vision. Characters do not inherit a new world. Often, they inherit a new way of understanding the old word. And this new way of understanding allows them to see the old world anew” (Rosen xxiii).