Tales from Creedmoor: A History of Abuse of Power

Bounded by 4 of the busiest thoroughfares in Queens – Winchester Boulevard to the west, the Grand Central Parkway to the north, Cross Island Parkway to the east, and Union Turnpike to the south – Creedmoor Psychiatric Center stands, pristine and unassuming. Ambulances and cars pass in and out through the security gate on Winchester, facing the expansive baseball fields of Alley Pond Park. Looking at this idyllic scene, with cars rushing past overhead and perhaps children playing on the ballfields, the casual observer could never guess at the hospital’s often-lurid history of governmental circumvention of our justice system and oppression of the historically disenfranchised groups it is supposed to protect.

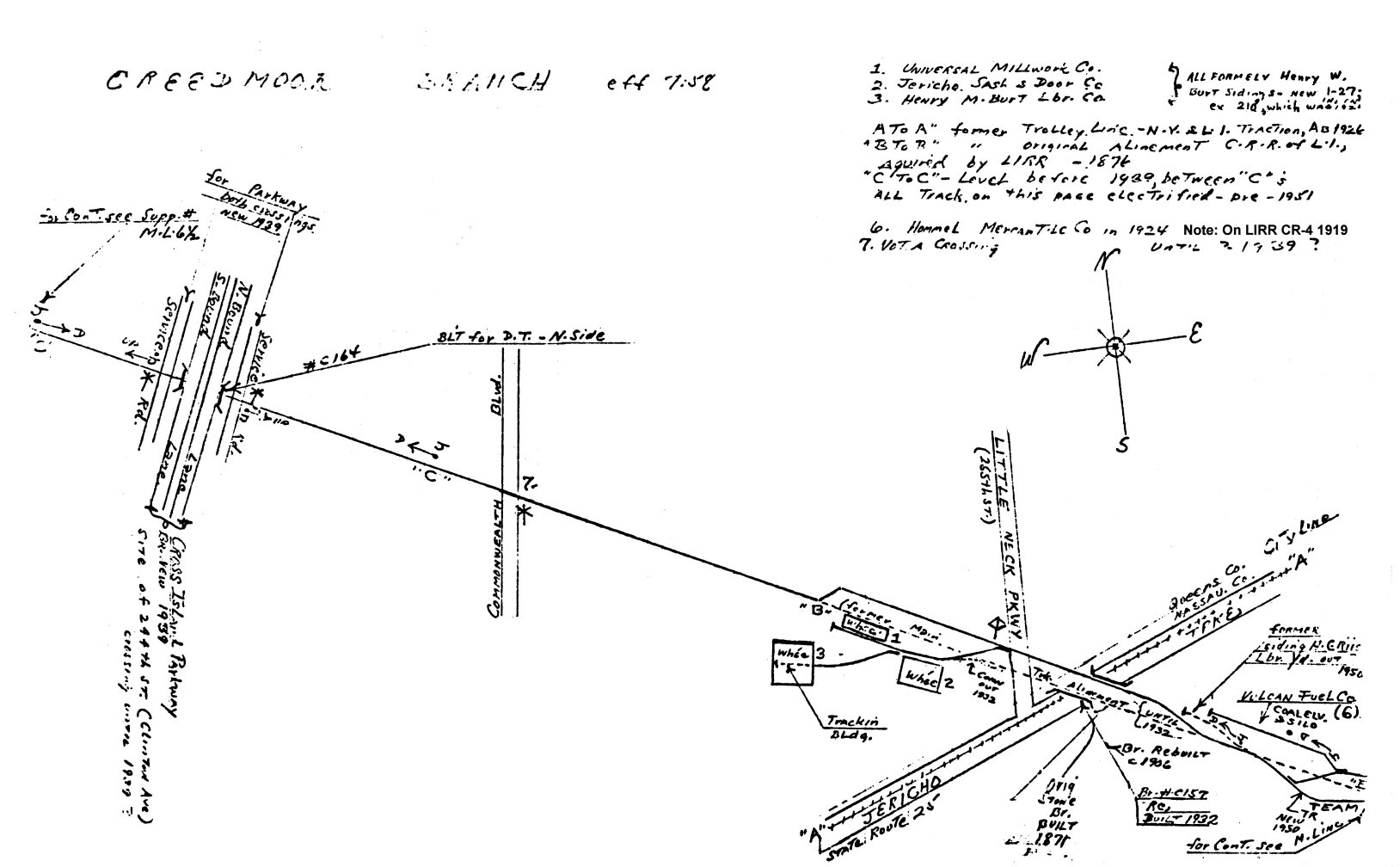

The use of Creedmoor’s land dates back to the Creeds, a family of farmers who worked the land and served as its namesake. The land was purchased by the government, who sold it in 1871 to a burgeoning hobby group headed by Civil War General Ambrose Burnside known as the National Rifle Association (which might sound familiar). The New York Times maintained a faithful column of the shooting competitions taking place for years thereafter. The land being deed back to the State in 1908, as Governor Hughes decided such competitions were exceedingly dangerous. The land was soon afterwards designated by what was then known as the Lunacy Commission as suitable grounds for a mental hospital, known as the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center.

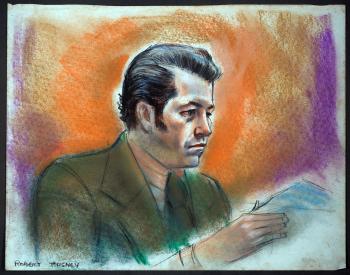

In the decades since its inauguration, Creedmoor has, more often than not, been the epicenter of state violence and of the perpetuation of that violence. Like many other prominent government facilities, Creedmoor has served as an organ of racial injustice. On November 25, 1976, NYPD Officer Robert Torsney shot 15 year old Randolph Evans in the head after responsing to a call in Brooklyn that had since been resolved. Torsney was charged with second-degree murder, but pled not guilty by reason of insanity in court. The insanity defense proved successful, and he was committed to Creedmoor a year after the killing. There he stayed for a year and a half before being released after the staff found that he suffered from no mental defect and was of sound mind; the Director of Creedmoor, Dr. Werner, stated at the time of his release that Torsney had “recovered from his psychotic episode, [showed] no evidence of mental illness and [was] not considered dangerous to himself or others”. No further legal action was taken against Torsney, who killed a 15-year-old boy, was found not guilty, and released from a hospital in the span of 3 years.

While Creedmoor has served as a sort of legal asylum for police officers accused of wrongdoing, it has done a rather poor job of providing for the people it is actually supposed to protect. In May of 1984, Roberto Venegas, Colombian immigrant and recent admittee to Creedmoor’s notorious Secure Unit, was killed after numerous “procedural oversights” on the part of Secure Unit staff culminated in his suffocation. Against regulations, Venegas was sat upon by multiple “therapy aides”, placed in a double restraint (a sheet placed over a straitjacket), tied to the wall, and struck with a club that an orderly had snuck into the unit… all, according to the accused, in an attempt to “restrain” the “agitated” Venegas. The autopsy showed that Venegas had died of a crushed throat, something that the accused, Mr. Cecil Haynes, categorically denied: “On the day he died, nobody hurt Mr. Venegas.” The only person who witnessed this was another inpatient, and his testimony was dismissed. In December 1985, after a speedy trial, Haynes was acquitted of all charges.

My family has borne firsthand witness to this abuse of authority. In my research of Creedmoor, I asked my grandmother if she had any stories to tell of the old facility. She told me she had but one, but it was easily one of the craziest stories I’d ever heard. Long ago (she can’t remember exactly when), my two uncles “borrowed” my grandfather’s car for a joyride down Winchester Boulevard, despite neither having had a license at the time. Being the inexperienced drivers they were, they inevitably crashed into the fence surrounding Creedmoor’s courtyard. Imagine their surprise when, without warning, the engine fizzled out, then burst into flames. This would not have happened had they crashed into a normal fence, but of course, they hadn’t. As they discovered, the fence was electric, to shock any patient who attempted escape. Nevermind any patients with cardiovascular issues; nobody got out.

What’s next for Creedmoor? According to sources linked to Community Board 13, plans are buzzing around some of the buildings that have fallen into disuse on Creedmoor’s land. The most comically warped of these that I read was the plan to demolish the long-abandoned, asbestos-ridden power plant and erect, in its stead… a YOUTH CENTER. Seriously. These people are so out of touch with the community and so comprehensively lacking in compassion that you can’t help but wonder whether it’s intentional.

The land on which Creedmoor’s all-too-proud façade stands has played host to a long, sad, checkered history of sweeping legal and bureaucratic abuse under the rug. It has given safe haven to the murderers of children and of the mentally disabled, and if there ever is punishment for these, it always – always – amounts to a slap on the wrist. For a facility bounded by such busy thoroughfares, it feels awfully boxed in.

WORKS CITED

Court of Appeals of the State of New York. Torsney v. Gold. Leagle.

“Dengrove”. NYPD Officer Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity for Shooting Ninth-Grader Dengrove, archives.law.virginia.edu/dengrove/writeup/nypd-officer-not-guilty-reason-insanity-shooting-ninth-grader.

Gannon, Michael. “State Proposes New Creedmoor Projects.” Queens Chronicle, 1 Dec. 2016, www.qchron.com/editions/eastern/state-proposes-new-creedmoor-projects/article_f0152465-0bb8-5814-91ec-dd896a08e667.html.

Goldstein, Tom. “Split Appeals Court Orders Torsney Freed From State Mental Hospital:” The New York Times, 10 July 1979, search-proquest-com.queens.ezproxy.cuny.edu/docview/120803964?accountid=13379&rfr_id=info:xri/sid:primo.

Prial, Frank J. “FOLLOW-UP ON THE NEWS; Court Confession.” The New York Times, 29 Dec. 1985, www.nytimes.com/1985/12/29/nyregion/follow-up-on-the-news-court-confession.html.

Shenon, Philip. “FEAR AND BRUTALITY IN A CREEDMOOR WARD.” The New York Times, 18 June 1984, www.nytimes.com/1984/06/18/nyregion/fear-and-brutality-in-a-creedmoor-ward.html.

“THE TRANSFER OF CREEDMOOR.” The New York Times, 29 Jan. 1890, search-proquest-com.queens.ezproxy.cuny.edu/docview/94746537?rfr_id=info:xri/sid:primo&accountid=13379.

My Grandma.

PHOTOS USED

http://www.trainsarefun.com/lirr/creedmoor/Emery-Map-CreedmoorBranch-NWfromLIRRmain_Emery_7-1958.jpg

By: purplesunburn | Posted: May 16, 2019 | Filed under Stories.

Powered by WordPress using the F8 Lite Theme

subscribe to posts or subscribe to comments

All content © 2025 by A People's Guide to New York City

Log in