Contextualization

The complexity of the socio-political atmosphere of the United States is enriched by the influx and presence of immigrants, but they face conflicting — and oftentimes precarious — situations upon arrival. U.S. Americans harbor vastly differing sentiments from one another, especially with regards to such a delicately important topic; as a result, immigrants might experience attitudes ranging from exclusionary to inclusionary, pluralistic to exceptionalist, or, hopefully, the model emulated by Jane Addams: the U.S. Tradition of Hospitality. Immigrants of a plethora of backgrounds arrive with varying expectations, hopes, and plans, finding their own individual ways to cope with an unfamiliar country: assimilating, maintaining ties to their countries of origin, or some blend of both.

Assimilation vs. Accommodation

Cover of the book “Toppling the Melting Pot”

Source: Indiana University Press

The cultural web of New York is, in theory, welcoming of transnationalism and specifically of Trans-Americanity (in which case one maintains ties to one’s country of origin in addition to America), though not always in practice. We spoke with Professor Moustafa Bayoumi and Professor Mariya Gluzman, both of whom belong to Brooklyn College humanities departments; we inquired about their personal experiences and opinions in regards to their immigration to New York, with a concentration on how they view their roles in higher education. As explicated by our two interviewees, immigration is a taxing and arduous process both bureaucratic and otherwise — Bayoumi and Gluzman each touched upon the debate of whether to assimilate or not, for instance, and how even after doing so one might face unfathomable discrimination. And as posited by both, U.S. America is a place capable of being — a place that should be — simultaneously loved and critiqued; in Bayoumi’s words, we must criticize the US where needed in order to “make the country the best it could be.”

There are several reactions immigrants generally face upon arriving in a new country. In his Toppling the Melting Pot, José-Antonio Orosco explores Jane Addams’s concept of the U.S. tradition of hospitality, the ideal approach to treating immigrants. Combating the concept of Western exceptionalism, which preaches the superiority of the U.S. American people, Addams’s proposition is fundamentally pluralist, its origins stemming from William Penn’s inclusive practices. One aspect of this notion respects the self-determination of immigrants entering a community, as opposed to imposing assimilationist attitudes. It also stands by the belief that the American people must respond to the concrete needs of immigrants entering a new community — food, shelter, schooling, forms of protection — and ultimately, welcome them as equal beings to learn from. Contrarily, if U.S. Americans repressed immigrants upon their arrival, Addams suggests that there would be “more violence and social unrest” (Orosco 102). Thus, the inclusivity promoted by pluralism is not only for the benefit of immigrants; similarly, it not only improves the society that already exists in whatever place is in question, but it enriches it and provides a better experience for everyone involved. We as a group have adopted this model as the one to strive for, in spite of the fact that it is often overshadowed by less rational, more pernicious behaviors.

Injustice in Justice: The “Immoral” Morality of Citizenship

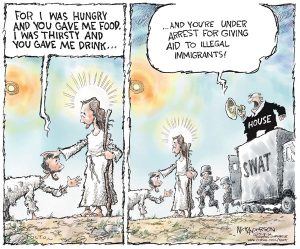

Jesus Christ providing aid to illegal immigrants. Source: “The Cartoonist Group”

Consequently, we must bear in mind that citizenship is merely a legal status; we must bear in mind that the U.S. is a country of immigrants. There is, sadly, sometimes injustice in enacting the law, as we realized upon reading Arthur Miller’s A View From the Bridge. His characters grapple with a tense situation that hinges on the debate between legality and justice — when two Italians arrive illegally in the U.S. to attempt to assist their families, as the plot goes, do they genuinely deserve to be jailed if caught? It is often difficult to separate out morality from what we are told is “right,” but in such a torn political climate as we are in currently, it’s crucial that we remain educated, aware, and respectful, especially towards immigrants who don’t have the path to citizenship that most of our ancestors did.

A vital component of this process of seeking to understand includes educating ourselves on the reasons that people immigrate to their America. We should inquire about their unique stories as well as recognize the qualitative habits they bring to communities. Regardless of whether immigrants are home-seeking, like in the case of refugees, or job-seeking in search of additional opportunities, this mutual respect and desire for understanding must guide the conversation. The home-seeking, job-seeking dichotomy alone is problematic, and it in itself could be interpreted as an assumption about the ‘immigrant agenda’ that some fear.

A United America: Transcending Political & Cultural Boundaries

Though they are leaving their country of origin behind physically, immigrants often remain emotionally connected to it, bringing with them values, culture, and other remnants of their old lives. Professor José David Saldívar, with whom we had the pleasure of speaking, wrote Trans-Americanity: Subaltern Modernities, Global Coloniality, and the Cultures of Greater Mexico, in which he describes this blending of the life one had with the life one then creates in America. He calls this “Trans-Americanity,” a form of transnationalism, which would consist not of assimilation but rather of one keeping a bond with both where one is from and where one ends up — an immigrant might consider more than one country to be ‘home.’ “Trans-Americanity” specifically refers to a bridge between North, Central, and South America; there’s a rich political, economic, and cultural exchange, and there are many Americans who live in that transcultural space. And there is something inspiring in this, because the richest of cultures are diverse and wide-reaching, as we like to imagine New York is, and as our interviewees feel America could be.

Statue of Jose Marti in Central Park, Source: Central Park Conservancy

We asked professors Saldívar, Bayoumi, and Gluzman whether or not they think that there is one united U.S. American culture, given that we are a nation of immigrants. Professor Saldívar replied that there is in the sense that we have a shared history (e.g., of colonization and slavery). Professors Bayoumi and Gluzman, on the other hand, both responded that there is no single American culture; rather, there are multiple. The beauty of America lies in its breadth, its capacity to host a variety of practices, faiths, peoples. We ought to eradicate dividing notions that stem from oppressive origins, like the concept of “American whiteness” that author and professor José Jorge Mendoza outlines in his article “Latinx and the Future of Whiteness in American Democracy.” As Mendoza notes, “whiteness” is not fixed, nor does it refer to the same group of people throughout history. But this shouldn’t be the crux of the conversation; white, brown, black, etcetera: all of these terms don’t even scratch the surface of humanity; they are merely vain terms assigned to group people, and there is an arbitrariness to separating people on the basis of skin color. The poet José Martí, in his book Our America, expresses the superficiality of races — race is an invention, every person is equal. “There can be no racial animosity, because there are no races” (Martí 238). If we can manage to focus and embrace the fact that we are all simply human, we might grow to disregard what we view as barriers between one another and instead see them as wonderful differences that can unite without negatively dividing us, as in the case of sharing culture.

The Individuality of the Immigrant Experience

Children waving at the Statue of Liberty. Source: U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

In attempting to further understand the immigrant experience, it is not a complete effort to generalize and assume that all experiences and backgrounds are alike. Thus, in our interviews, we also aimed to uncover what made professors Bayoumi and Gluzman unique in each of their immigrant experiences, and ultimately, develop insight into the complexities of the broader immigrant experience. We touched upon themes such as a need for a clearer path to citizenship, the distinction between a refugee (whose country of origin is oppressive, e.g., forcing people to flee; Professor Gluzman, for instance, is a Soviet refugee) and an immigrant, the struggle between a desire to fit in and a desire to retain one’s past identity, and the journey to recover it if it was abandoned, as Professor Gluzman revealed she had. We also focused on our interviewees’ roles as educators, and we found (as can be seen in the ‘Transcripts’ section of our website) that both feel a sort of responsibility to assist students and cultivate a warm environment, especially as both Professor Bayoumi and Professor Gluzman understand on another level how it feels to not belong. Professor Bayoumi involves himself with political activism, speaking out both here in the U.S. and in Canada, where he grew up for much of his life; he advocates in order to better America.

The interviews revealed to us the debt some feel they owe the U.S., whether or not they retain loyalty to their countries of origin. The U.S. can certainly do better in regards to nourishing and cultivating immigrant life, and, again, to go that extra step past toleration and to build a joint community; yet, there is still a greatness to the larger nation of the U.S. — the general U.S. ‘people,’ though it’s admittedly disjointed in places — and maybe that stems from the forward-thinking attitudes of some of its inhabitants. Projects like these give us a platform to discuss these philosophical notions and their implications. We hope that by helping people express their stories, their personal immigrant experiences, we can lend a better understanding of the broader socio-political issue to anyone who might visit our website and to anyone open to conversing about such a relevant and significant debate. As Professor Bayoumi articulated, immigration has become so politicized that we lost the humanity of the situation — we will now strive to bring it back.