Google Images

Throughout the course, there were a lot of interesting musicians, artists, and historical figures but ten really stuck out to me. The following are my top ten favorite works.

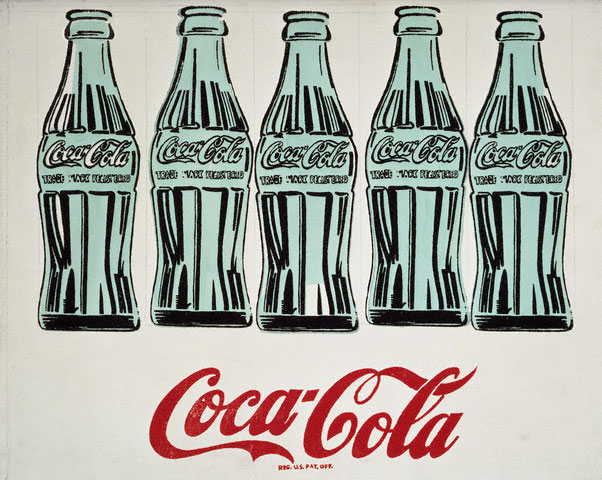

- I think the artist that had the most impact on me would have to be Andy Warhol. He is the man throughout this course that I admired the most because he is New York. And his painting, Green Coca-Cola Bottles, especially interested me. This was part of his “Pop Art” movement and with these bottles, Warhol was trying to say a radical statement of equality. If Marylin Monroe drinks Coca Cola, if the president drinks Coca Cola, and if you drink Coca-Cola, there isn’t much difference between you three. In fact, YOU could even aspire to be the president! How about that!

-

Google Images

Another piece that I like, also from Warhol was his film Chelsea Girls. I liked the way it was all-inclusive and the way that Warhol tried to show sexuality in its entirety. He dealt with such topics as sex, drug use, same-sex relations, and the transgendered in ways that were not socially accepted by his conservative society at the time. It’s truly remarkable the strides he was able to make and I like to think that his shocking efforts at the time made it easier for others to come in after and fight for sexual equality. I only hope I will have half as much courage as Warhol in the things I do.

-

Google Images

When we went to the Morgan Museum, what struck me was the way the two older museums was connected by this new modern, glass area with high ceilings and steel trusts and beams. But what was most interesting about the new modern glass building was the way it worked with the older architecture of the morgan museum. It did not, unlike in most of New York City, outshine the old and I think that was a very important componeent of the design. The new glass building paid homage to the old while still looking towards the future. In fact, the glass seemed better suited to enhancing the beauty of Pierpont Morgan’s museum rather than anything else.

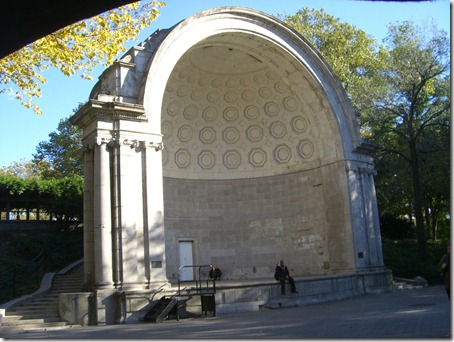

Central Park

- Central Park is another example of blending two seemingly different things. In this case, Olmstead managed to blend the nature and the city. Not too long ago when I walked the park, I got lost somewhere in the middle of it and I stumbled upon a walkway that went either up to an elevated lookout onto a pond or down to an amphitheater where some woman was singing opera. It all seemed ethereal like I was transported to 16th century England. But hardly twenty minutes before I was at the corner of 68th and seventh, trying to weave my way through incoming lanes of traffic. I’d like to think that Olmstead knew that New Yorkers who walked throughout his park would not forget the hustle and bustle of the city they just came from but he did the best to quietly envelop them with the quiet of nature. Central Park allows me to forget about the city but Olmstead knew that his park couldn’t block the skyscrapers that teetered on the edges of the park. He knew that his park would be one that reckoned nature with the city and this is why I love Olmstead’s vision for Central Park.

-

Google Images

I felt a sort of glimmer of hope coming from the Jackson Pollocks “Fire”. In the way that fire can destroy, it also gives life. Like the way a phoenix is reborn from the ashes of fire, I felt like Pollock was trying to say something similar about the American society during the Great Depression. That through all this pain, all this anguish, all this death, it gets better. That America can be reborn from the ashes, shown by the arms crawling out of the fire, from this place of pain come the new Americans. This really struck a chord with me because of the immense amount of hope it gave to me and the others who looked upon it before me.

- Whitman I feel is a poet that encompasses New York in her fullest. In this brief excerpt from his poem Manhatta, I get the sense of universalitity, this cosmopolitation vibe from New York. This celebration of people–not people in singular but people in the plural sense of it. Whitman celebrates everyone and is proud that his city is free and is a city of zero slaves. He is also proud of the chaos of the city, the spirit of the city, the loud noises and the crowded streets. There will never be another New Yorker as in tune with his city.

Trottoirs throng’d—vehicles—Broadway—the women—the shops and shows,

The parades, processions, bugles playing, flags flying, drums beating;

A million people—manners free and superb—open voices—hospitality—the most courageous and friendly young men;

The free city! no slaves! no owners of slaves!

- George Gershwin was another man who dared to critisize the social norms of his time. He grappled with social justice in a racial perspective. Gershwin’s jazz-inspired Rhapsody in Blue confused many critics. They were unsure where to place Gershwin’s novel composition. Some critics saw it as blasphemous to classical music, others saw it as pure genius but the public overwhelmingly loved “Rhapsody in Blue.” At this time, jazz was still derogatively referred to as “sex music” in elite circles. Jazz music was commonly associated with African Americans and ran antithetical to the narrow structures of classical music. Gershwin however, had years of experience as a song plugger and played all kinds of music and in doing so, he saw the beauty of jazz, he saw the beauty of classical music and realized that they were both beautiful in their own

separate ways. Heres a clip of Gershwin’s famous song

separate ways. Heres a clip of Gershwin’s famous song - Maggie, Girl of the Streets really tore at my heartstrings. My pity went out to Maggie. Maggie who was one of the purest people I’ve ever seen was faced with cruelty after cruelty. In this course we’ve talked about social justice and what is “fair” and what is not and I feel that Maggie got the short end of the stick in every case.

- When I look at the Empire Stae building, all I see is its magnificence but in thsi course I learned that it was an intial failure and if such a wonderful, groundbreaking building can be seen as a failure when it first came out then that gives me hope that every mistake I make, may prove to be more valuable than I origionally thought.

- I’ve known Jacob Riis for a long time. In fact, ever since elementary school I’ve admired him. Partly becuase my elementary school was named in his honor and partly because of the things he did, I felt a real affinity for this man and during this course I was able to rediscover my love for him. He is truely a mangnificent man, not without his flaws of course, but an interesting and influential man nonetheless.