International Center of Photography: The Cuban Revolution

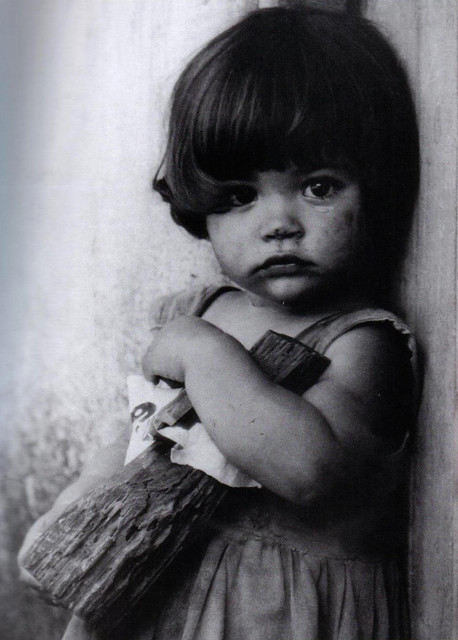

La Nina de la Muneca de Palo by Alberto Korda (1958)

A Cuban Revolution is taking place at ICP’s basement. The works of over thirty photographers are the remaining ancestors of the revolution, capturing the humanity of a people’s struggle to govern themselves.

Today’s daily reminders of the Cuban Revolution are usually one of three things: the Cuban Missile Crisis, the stylish Fidel hat, or a Che Guevara t-shirt. Concerning the third, Alberto Korda’s heroic image of Che, known as the Heroic Guerilla, reminds us of the figure that incited a revolt with Fidel Castro against Batista, a corrupt dictator of Cuba (1940-1944; 1952-1959.) Nevertheless, this polarizing propaganda does little to depict the suffering of the average underprivileged Cuban citizen.

Upon walking around the exhibit, the curator’s design catches your attention. His placement of the pieces disintegrates the reality of life before and after the revolution from the heroics attributed to the years in between. In a brilliant sequence you can find the wealthy celebrating in festive hats at American-installed casinos. In another shot there is a glamorous depiction of a showgirl who could easily be mistaken for a prototype of Marilyn Monroe’s classical white dress image. Then immediately you begin to witness the progression of time right before your eyes as you approach various shots of Che and Fidel Castro: some where Che is posing shirtless like an actor and others where the two are among a stockpile of artillery with a radical joy pasted across their grins.

However, there is one photo that stands out and pressures the viewer to forget about the faces and ideology clouding the revolution. One of Korda’s photographs, La Nina de la Muneca de Palo, would better serve as the face of the movement. A young girl grasping a wooden stub dressed in white fabric like a doll of an indistinguishable gender conjures a figure between a woman dressed in a beautiful white dress or a man in a starched straightjacket; both the tragedies of the revolution. This historic record serves as a reminder of the decline of the wealthy and the blistering insanity of Che’s radical approach.

Among this shot, there are others showing the elderly struggle and the young men raising AK47, the last of which display never before seen photographs of a cold blooded and dead Che. The exhibit is organized chronologically, with photos strategically introducing details that foster the reality of each subsequent shot. Appropriately, viewers are reminded of the historical nature of this exhibit and the fundamental significance of photos as a historic medium, in general.