Category — Site Authors

FRESHMAN!

Freshman Friday is certainly a day of horror for newcomers in high schools that honor this tradition. Fearing lockers, toilets, and garbage cans, freshmen may attempt to hide from the upperclassmen bullies who take pleasure from their fright and embarrassment. It appears, however that such cruel rituals fade away in college, perhaps due to a change in students’ maturity and a new perspective on what freshmen mean to their school. Instead, freshmen are welcomed and are often given attention and guidance. Giving clubs, teams and other organizations the opportunity to expand, freshmen are also received warmly and treated with enthusiasm.

Despite this seemingly stark contrast between high school and college freshmen, the traditions that emphasize the rookie status of newcomers is inescapable. During my visit to Williams College last weekend, I watched a home football game against Wesleyan University. It did, however, lack the excitement that comes with tight competition. Wesleyan’s defeat was evident even in the second quarter, and a few spectators, including myself, left before the end. I was under the impression that the peak of the day’s thrills had been reached at the close of the victorious game. Although I had long been gone from the football scene, my best friend, Eilin, urged me to head back to the area near the field. “We know they won! It’s over!” I argued. I was too lazy to return to the other side of campus. “Come on, there’s something I want you to see over there,” Eilin insisted.

I reluctantly walked back with him, and stopped just a few blocks from the field, where a sizable crowd was gathered with flashing cameras. There was cheering and laughter, but for what? I wondered what was going on. After a couple of seconds, I saw a few of the football players in the center of the crowd. Their hair had been cut and shaved in various amusing designs. “Wow,” I said aloud. Suddenly, I heard Eilin burst into a loud and shameless guffaw. “Oh my god! That’s my friend … over there!” he cried in the middle of his hysterical laughter. I looked over, and sure enough, it was one of his friends from the football team. There were random patches of hair left on his head. It looked as if a monstrous little five-year-old had cut his hair with both eyes closed. I turned to Eilin, whose laughter had finally died down into a smirk. “Well,” he began to explain, “It’s a tradition that if we win the last home game, the freshmen players get the craziest haircuts while the town watches!” I must admit, I thought it was rather funny, but that’s when I realized that no matter where one goes, a freshman is still a freshman, even if he is a champ!

November 13, 2010 1 Comment

Belinda Chiu/”Make Your Mark”

[photosmash=]

People have different ways of expressing themselves in the form of art; some people paint, others sketch, and in my neighborhood Elmhurst, people do graffiti. I decided to choose the theme of “Make Your Mark” and took photographs of different forms of graffiti in Elmhurst and in Woodside.

To begin with, I made sure my camera was in the setting of “Day Light” since these photographs were taken on sunny days. I put the flash on automatic so my camera would automatically detect when it needed more light or when it did not. On my way to the train station, I passed by the park near my house and came across a tree with the carving: “CARLOS ♥’S MARIE.” The carvings seemed to have been etched out using a carving knife, for every letter was crudely cut and the round letters such as the C and the O were jagged. I specifically chose all of my photographs of graffiti as the center of the picture so it would be the focal point. There are numerous Chinese supermarkets in my neighborhood, all of which do not open until after eight o’clock, and in the span of dusk to opening time, people take advantage of spraying graffiti on the metal gates. I stood at one end of the gate and took an angled shot of the stark white graffiti spray on the dull gray gate.

For this project, I roamed my neighborhood to find the generic graffiti on the walls of apartments and stores, and took shots of as many graffiti art as I could. I was particularly entranced by a form of graffiti art next to a club Nuves on Queens Boulevard, which features a person driving a blue car with smoke trailing behind him, and a large panther crouching down glaring at any bystander that passes by. A few years ago, this graffiti used to be a bland image featuring only dull, dark colors, but now it is enhanced with bright purples, blues, and pinks to attract the attention of passersby. I changed the setting of my camera’s color to “vivid” to capture the vibrant colors of the graffiti.

I recalled passing graffiti numerous when I was driven to Woodside; a particular form of graffiti was always drawn under the overpasses of trains. These graffitis were always painted by “Two Famous Artists,” artists that I have always admired. They always sign their names and label their art, and at this location they named their artwork, *WOODSIDE on the Move.* Over the years, their works have been graffitied over by other people, which made it difficult for me to take quality photographs. They use the entire canvas of the walls under the overpass, which presented difficulties for me to take photographs of the entire canvas. I stood at one end of the photograph of the horizon and the baseball teams and did my best to capture their entire works. There was a photograph I took of a series of colorful boxes which were shadowed by trees; I tried to reduce the shadows from the tree by increasing the exposure, saturation, and the shadow of the photograph using iPhoto, and decreasing the contrast of the picture. The photograph of the flowers were also shadowed by the tree leaves, so I used iPhoto again to increase the saturation and highlights, and decrease the exposure and contrast to capture the colors of the flowers that I saw in person. The ocean painting was extremely large, and I was unable to capture the entire picture even from standing across the street, and one of the beams obstructed my view of the painting.

Performing this project was extremely enlightening for me because I noticed I overlook the details of the neighborhood I have lived in my entire life. This project helped me be more observant to my surroundings and learn to make use of the myriad settings my camera has to offer and make use of adjustments I can do with iPhoto.

November 13, 2010 1 Comment

Photoshoot in Central Park

“Go stand over there,” Steven ordered, “no wait, go a little more to the side, I need more light otherwise the picture’s going to come out bad.”

“You’re embarrassing me by making me do all these random poses in front of passersby!” I argued with him.

I met up with my friend, Steven, to take photographs for the collage project due in a couple of weeks. Since I wanted to take many pictures of nature as well as the humans’ effect on nature, I decided to use his expert photography skills to capture every image I wanted portrayed in the collage.

Knowing him since high school, Steven was always fascinated with photography and photoshopping photographs he took or finding images online and enhancing them to the potential he wanted them to be. I always thought it was a mere hobby of his until I saw how he was performing today. He carried around his messenger bag filled with his alternate lenses for his camera.

Carefully angling himself to the direction of the image he wanted to capture, he would walk around a couple of inches here and there until he took the perfect photograph. As a deal for coming out of his house, I was required to have my photographs taken as well… At first it was really uncomfortable considering we were in public and he would stop me literally every couple of feet, but I grew to realize that this was his way of perfecting his photographing skills.

As the sun went down, I sat down with him on a park bench as he showed off his photographs to me, and I was impressed. His constant switching of camera lenses paid off, as well as arranging me and the setting of Central Park in accordance with the amount of lighting the sun provided; his past photoshoots with his friends definitely paid off in his photography skills.

November 13, 2010 No Comments

Fleeting Glimpses

Fred Stein, “Gerda Taro and Robert Capa on the terrace of Café du Dôme in Montparnasse, Paris”

Stepping out of the rain into the International Center of Photography, I welcomed the light and warmth of the building’s entrance and main lobby area. It was when I had caught my breath and started to look up, however, that the true power of the Mexican Suitcase exhibit hit me.

The exhibit consisted of a collection of long lost negatives that were taken during the Spanish Civil War. The three photographers whose works were in the Suitcase (Robert Capa, Gerda Taro, and Chim—real name David Seymour) were all closely involved in documenting the wonders and horrors of this time of turmoil in world history. As I followed the gentle flow of people passing along the length of the carefully crafted exhibit, I found myself surrounded by not only pictures of the actual events of war, but also the documentation—the permanent depiction—of common people who lived during this time: people who breathed the electrified air of discordant opinion. Seeing the faces, the expressions of these people—not just images of soldiers, political leaders—gave new perspective. Often, when we reflect upon history, we envision only those directly involved with wars, battles and conflicts—But what of the rest of the world?

ICP reinforced this revelation by exhibiting different media representations of the conflict: one such example was the French news magazine Regards, which used many of the lost pictures from the “Mexican Suitcase” to actively chronicle the events of the Spanish Civil War. These glimpses, however fleeting, into not only the major events but also the more individualized repercussions of this conflict, gave much more of a platform on which to appreciate both the events themselves as well as the view that the photographers Capa, Taro, and Chim were able to capture in such a turmoil-ridden time.

One aspect of the exhibition that successfully heightened both the emotion and relevance of the photographs specifically, as opposed to what major events they captured, was the curator’s choice to explain the relationship between photographers Capa and Taro. Although they worked together, that was not the extent of their relationship—they were romantically involved as well. Looking at their photography—and seeing pictures of them, smiling and interacting–one can imagine how they saw the images they captured through both a literal and metaphorical lens, as well as the joys (and tragedies) of their relationship. They witnessed these events happening, and we can see the emotion in the faces of those in the photographs–but the exhibit’s efforts to give some background on the photographers’ work allows viewers a tiny, yet significant glimpse into someone else’s reflection on the events they viewed as they were happening: a dramatic revelation that makes our response today, however removed from these events we may be, that much more powerful.

I walked into the International Center of Photography with a dry, simple notion of what happened during some turmoil at some time in history. However, after seeing through the eyes of those who tried so hard to capture the truth, the real events that affected real people—people I’ll never meet, some I’ll never even know the names of—I left with a newfound appreciation of the gravity of the events that affected the people in and around the Spanish Civil War—something that no textbook could ever hope to achieve.

November 11, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Cuba in Revolution

www.nyphotoreview.com/PANPICS/AlbortoICP.jpg

Cuba in Revolution explores everyday life in Cuba before and after the Revolution around the 1950s. This exhibit showed life during a time of turmoil in Cuba and captures the images, faces, and emotions that we don’t usually see. These many photographers managed to take shots of many different aspects of Cuba during these times, including economic, political, and social aspects.

This exhibition shows the tremendous influence of photography in recording the revolutionary movement in Cuba. As I passed each image I noticed the progress and the order of the images. At first it seemed as if the state of Cuba was not under political turmoil. There were a series of photos where there are just many kids and men in the streets laughing and smiling in front of the camera. It had a happy, light-heartened feel to it. But as the photos and years progressed, so did the portrayal of violence and misery. The photos became more impoverished and sad looking.. It focuses on showing us the emotions and story behind the everyday people in Cuba, both involved and not involved in the revolution itself. The revolution affected everyone, and many people were dragged into situations that weren’t very suitable for them. For instance, in a glass window at the exhibit, I saw a newspaper image in which there was an old lady amongst many young men and women, and she was prepared to fight. She looked twice the age of everyone there yet she was being thrown into this mayhem. There was another image of a poor looking boy stuck in the middle of everything. Age didn’t matter. War and violence showed no mercy to anyone. This corrupt time enabled the photographers to capture the affect it had on citizens of all age and size.

The most famous photograph at the Cuban Revolution exhibit as I later found out was the photograph titled, “Heroic Guerrilla”, which showed Che Guevara’s stern brave face. I found it interesting how that is the most famous photo of one of the most influential men in Cuban history… And then right after that picture, there is an entire room dedicated to his death. It went from “heroic” Guevara to “dead” Guevara. To me it embodies the rise and fall of Guevara-Castro and how far one man can fall from grace and lose so much. He went through a certain heroic cycle leading up to his execution and I think that sums up the exhibition itself. The whole exhibition shows this power struggle and the transformation from a solidified nation to one with great chaos.

Overall, I enjoyed my first visit to the ICP exhibit. Cuba in Revolution gave me good insight to not only the revolution itself with the major political figures, but also with the citizens stuck in the middle of everything. These photographs help capture their story and misery in a way we wouldn’t see and understand otherwise.

www.nyphotoreview.com/PANPICS/AlbortoICP.jpg

November 11, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Walking through History

Photography is a coexistence of remembrance and reminiscence in our lives. Like the old black and white photos, memory and history are fused together to project moment through a unique angle. International Center of Photography serves as a storage of various moments of history: it collects and combines different perspectives altogether. The exhibition that I went last Thursday was “The Mexican Suitcase: Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives by Capa, Chim, and Taro” and “Cuba in Revolution.” These photography exhibitions showed how media utilizes photography to control public opinion and manipulate prejudice.

Upon entering the center, we were greeted by a huge image of film rolls showed in a sectored box called “the Mexican Suitcase” in front the main entrance of ICP. The first exhibition contained photos taken by Chim (David Seymour) and other renowned war photographers, such as Gerda Taro, and Robert Capa, who eventually developed war photography as an independent genre. Their tiny suitcases were filled with more than 4,500 35mm negatives of the photos taken during the Spanish Civil War. This was the first time that they were openly exhibited after the films and negatives were lost and found few decades ago.

The most interesting perspective of this exhibition was that it put an emphasis on the influence of using photographs in media. Of course, some of the photos contained horrifying scene of violence, but most of them were depicting the people’s reactions toward the war. The original films and negatives were on the upper wall. Underneath them, there was a collection of magazines from different countries that used one photo to trigger different reactions from people.

Chim (David Seymour), [Two Republican soldiers carrying a crucifix, Madrid], October– November 1936. © Estate of David Seymour / Magnum. International Center of Photography. <http://www.icp.org/museum/exhibitions/mexican-suitcase>

One sector of the exhibition contained a photo, which depicted the Nazi German soldiers forcefully removing the treasures and art pieces from the Spanish Palace claiming that they can preserve them in a better condition. By using the same photo, German magazine praised their government’s generosity and respect toward Spanish culture, while Regards, the French magazine accuses the Nazis of robbery. Even though, the same picture was used for both media, the title and article generated entirely different atmosphere. Media kindly blocked the people’s vision to generate their own interpretation on the photo.

Osvaldo Salas, Comandante Camillo Cienfuegos and Captain Rafael Ochoa at the Lincoln Memorial, Washington, DC, 1959. © The Osvaldo & Roberto Salas Estate, Havana, Cuba, Courtesy The International Art Heritage Foundation. < http://www.icp.org/museum/exhibitions/cuba>

Downstairs, there was an exhibition about Cuban Revolution. Most of the photos were of portraits of the two leaders of Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. There were two photos stuck in my mind. One was of two Cuban officials, Commandant Cienfuegos and Captain Ochoa arrogantly standing in front of the statue of Lincoln at the Lincoln Memorial in their Cuban military uniforms. This uneasy juxtaposition of “the martyrs of communism” standing in front of one of the founding fathers of American democracy was both ironic and amusing at the same time.

Another photo was of Che Guevara’s stunned face with his eyes and mouth wide open. Before I read the credit and information below the photo, I didn’t know this photo was taken after his death. His expression was blank, but it was extremely hard to detect any sign of death in the photo itself. It was the moment when I felt the perception of reality was becoming vague. A photo, which is considered to be the most vivid record of history, could not explain the entire history by itself.

Throughout history, photographs were used as a dominant tool for polarizing opinions in favor of one side. That was my initial preconception toward photography. However, ICP exhibitions made me to redefine the role of photographs in our lives. If capturing the moment is a photographer’s duty, we, as viewers, are in charge of developing our own interpretation with open mind. We can either like it or hate it, but should not disregard the fact that there are always some emotions in our mind evoked by photographs. We should treasure such emotions and insights to avoid perceiving bias from the media.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

Crunchy Hello-O-Weeen!

One of the things I fantasized about American culture was definitely Halloween: children in their cute costumes walking door to door, shouting “trick or treat!” and collecting bags of candies that would last for a year. In my first year in the States, my aunt and uncle were reluctant toward my participation in trick or treating because of my Christian belief. Also, I was in eighth grade by that time and they thought I was too “old” for such a “baby thing.” When my friends wore their costumes going door to door, I pretended that I was “too cool and mature” to join the crowd. Actually, I was secretly jealous.

In Korea, I never celebrated Halloween. Koreans have two annual –not like as big as national holiday- rituals throughout the year that are based on the similar concept of Halloween. One is Jung Wall Dae Bo Rum, or sometimes interpreted as the Full Moon Festival, and the other one is Dongji. The full moon festival is around November, and Koreans eat nuts and peanuts on that day. In our tradition, the cracking sound of nutshell is believed to scare bad spirits away and bring fortune and health. Dongji is usually around the end of December; it is a day when the duration of night is the longest throughout the year. As a celebration, Koreans eat sweet red bean soup, Patjook, which has the brownish red color that is –again– believed to scare off the bad spirits.

After I came to the states, I could not find Patjook easily. The cooking process was rather time-consuming and the ingredients were hard to find. Also, it was so difficult to figure out the exact dates for those traditional rituals because they were changed every year according to the lunar calendar. I did not celebrate Halloween for a while. It was evident that I could never join the march of children for trick or treating anymore. However, I’m thinking about giving out almond chocolate and Crunch to my friends next year to introduce them about my Korean culture. Want some Crunch, guys?

November 9, 2010 No Comments

Cuba In Revolution

While on a class trip to the International Center of Photography I walked down a staircase and found myself in a visual history lesson of the Cuban Revolution, with time charts, descriptions, and most importantly photographs. These photographs brought history to life for me in a way that only movies, non-documentary films to be matter-of-fact, had done before.

As I walked through the halls of the exhibit I found that films like The Godfather Part II and The Battle of Algiers kept coming to mind. The exhibit started off with pictures of pre-revolution Cuba, in which mostly white people went to clubs and partied in what seemed like a post WWII paradise. As the exhibit went along though, it was soon apparent that there were freedom fighters like Che and Castro who opposed the American backed capitalist puppet government. I watched as Cuba’s prerevolutionary government fell apart as a new communist government was formed.

Knowing some the basic history of the Cuban Revolution, as well as some the major players I tried to, at first, look at the photographs before looking at the written descriptions and the broader explanations that accompanied each set of photos. The museum curators did a good job of setting up the exhibit in a way that allowed visitors to learn something new about an important historical event, but also appreciate the art of photographs.

Obviously there were some striking photographs, like a man sitting on a pole in a crowd of people and Castro shaking the hand of Ernest Hemingway, but what impressed me the most was the juxtaposition of the photos from before, during, and after the revolution. The first photographs I saw were lighthearted and suggested that everything was fine in prerevolutionary Cuba, that it was a peaceful country, some sort of paradise where people could go on vacation and lay on the beaches. But pretty soon, moving on to the next photographs the only thing one saw was the poverty that accompanied peasants in Cuba at the time. The juxtaposition of these images gets to the heart of why the Cubans people resented their prerevolutionary government so much and also demonstrates how photographers choose to persuade or suggest ideas in the pictures that they take.

Later on the tone and content of the photographs shifts dramatically, there is actually a revolution going on in Cuba which culminates on new-years eve 1959 when the famous collapse of the capitalist Cuban government occurs and would change the face of Cuba for half a century and onwards. Instead of white people in dresses and slacks dancing the night away the photographs turned to longhaired, weather-beaten men in military uniform celebrating their victory over the capitalists.

The mood of the exhibit then shifts again to an odd group of photos that portray the rebel leaders Castro and Che in a warmer light while they are taking a vacation. But, alas Cuba is still not perfect as we see the gruesome images of Che’s death in Bolivia. This is an odd group of photographs that sharply contrast one another, yet failed to provide this reviewer with any real commentary.

After this the exhibit seems to tapper out, as the photographs of post revolutionary Cuba are just not as interesting or well placed as the prerevolutionary and revolutionary photos. Another criticism I had was that most of the post-revolutionary photographs were one-sided arguments. They seemed to favor the revolution and did not address the major social and economic issues that faced the new Cuban post revolutionary government. Obviously since it was hard for Westerners to get to Cuba, let alone go to take photos that criticize the country, it might be the case that photos of this nature are just possible to find.

Overall though, Cuba In Revlution is a fully enjoyable and educational experience. It is not only a history lesson, but also a lesson in the use of photography to influence, persuade, and pass judgment on historic events. The exhibit proves that the most persuasive arguments don’t have to be written in the columns or headlines of newspapers, they can also appear as images that choose what to show and what not to show carefully.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

ICP: Cuba in Revolution

Photography is a unique art in several respects. For one, it has the ability to capture a single moment in time unlike any other medium of fine art; a capability that comes especially handy in moments of historical importance. Thursday’s trip to the ‘International Center of Photography’ highlighted two uses of photography during moments of historical significance. In the lower of two exhibits at the Center was Cuba in Revolution, a gallery comprised of nearly thirty different photographers’ work chronicling Cuba from pre-Revolutionary (~1950s) to the death of Che Guevara.

One of the most unexpected political episodes of the Cold War, the Cuban Revolution showed the rest of the world the power that a faction of young Communist rebels could wield. So powerful in fact that the group, led by Fidel Castro overthrew then President Fulgencio Batista of Cuba on January 1st, 1959. If nothing else, the Revolution highlighted the willpower and strength of the young men in Cuba.

Regardless of the photographer, the location, or the date of the photograph, each framed print invariably focused on young male faces, more often then not holding some type of firearm. This particular ‘theme’ lasted throughout the gallery and could not have better captured the events that were taking place in Cuba at the time. The black and white prints, many of which were vintage from the 1960s, also were unique in that a good majority of them possessed a great deal of detail in the background of the photos. Certainly video could have captured the main focus of what was going on in each particular picture, but only a photograph could have assembled the amount of detail that each shot had, essentially freezing a moment in time. And perhaps that is my favorite part of photography, the photographer’s ability to save an instant never to happen again.

Raul Corrales’ ‘La Caballeria’

Several of the photos that were on display were simply astonishing to say the very least. The ‘feature’ photo of the exhibit was Raul Corrales’ La Caballeria, a shot of the mass of horse riding, flag-waving members of the rebel’s cavalry. The shot itself is special as well; as from left to right, perhaps by design, it fails to contain the (perceived) enormity of the number of ‘soldiers,’ another interesting aspect is the great contrast between the white horse leading out in front of primarily darker horses. In a black-and-white print, the contrast stood out even more so because of the large disparity in the colors. My particular favorite of the show happened to be Alberto Korda’s Quixote of the Lamp Post. The photograph gained my liking particularly for its simplicity. It does not use odd angling or false lighting or any other technique rather it relies solely on the photograph’s subject, which is of a man smoking while sitting high atop a lamppost, above seemingly thousands and thousands of people, listening to a speech given by Fidel Castro. The simplicity in Korda’s picture however is not the exception to the set though, but for the most part, the rule. Nearly, if not, all of the photographs on display were of historically significant people or events; that being said, it is likely that each and every one of them were shot in natural conditions, which very well could have been unfavorable towards the photographer. Understanding this only calls for a greater appreciation of the resulting products, which were and still are important in fully understanding the events that transpired in Cuba over the years of the Revolution.

Alberto Korda’s ‘Quixote on Lamppost’

Alberto Korda’s ‘Quixote on Lamppost’

One of the focuses of the exhibit was on Marxist revolutionary, Che Guevara. In many of the photos presented of him, Guevara displayed an almost absence of emotion, whether it be in his military garb in public, or ‘relaxing’ on his own, he consistently and notably expressed a face of indifference. In fact, he was so emotionless that had one not been informed that one wing of photos of him was of him dead; it would be difficult to tell the difference. Perhaps though the most notable of all photos at the exhibit was Alberto Korda’s “Guerrillero Heroico,” a stoic portrait of Guevara, which has famously come to represent ‘rebels’ worldwide. The photo, which has been called one of the greatest of all-time (by some) possesses little by way of artistic technique, rather it merely captures Guevara in a moment of time; therefore it is the subject of the photo which has become renowned as opposed to its technique.

In reality, that same principle held true for just about every other photo on presentation, the greatest photographs on display were not those that were shot with special lenses or those that utilized different techniques; instead they were those whose subject matter meant the most. Considering the purpose of the photos as being documentation of historical events, fortunately they are viewed more so for their subject value as opposed to their skill, which nevertheless was very good.

November 9, 2010 No Comments

International Center of Photography: The Cuban Revolution

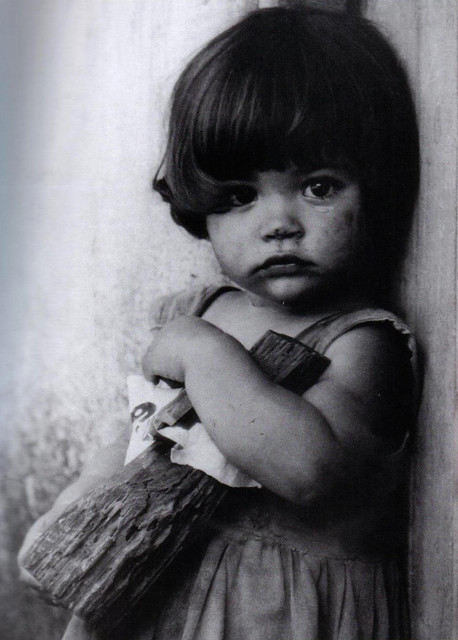

La Nina de la Muneca de Palo by Alberto Korda (1958)

A Cuban Revolution is taking place at ICP’s basement. The works of over thirty photographers are the remaining ancestors of the revolution, capturing the humanity of a people’s struggle to govern themselves.

Today’s daily reminders of the Cuban Revolution are usually one of three things: the Cuban Missile Crisis, the stylish Fidel hat, or a Che Guevara t-shirt. Concerning the third, Alberto Korda’s heroic image of Che, known as the Heroic Guerilla, reminds us of the figure that incited a revolt with Fidel Castro against Batista, a corrupt dictator of Cuba (1940-1944; 1952-1959.) Nevertheless, this polarizing propaganda does little to depict the suffering of the average underprivileged Cuban citizen.

Upon walking around the exhibit, the curator’s design catches your attention. His placement of the pieces disintegrates the reality of life before and after the revolution from the heroics attributed to the years in between. In a brilliant sequence you can find the wealthy celebrating in festive hats at American-installed casinos. In another shot there is a glamorous depiction of a showgirl who could easily be mistaken for a prototype of Marilyn Monroe’s classical white dress image. Then immediately you begin to witness the progression of time right before your eyes as you approach various shots of Che and Fidel Castro: some where Che is posing shirtless like an actor and others where the two are among a stockpile of artillery with a radical joy pasted across their grins.

However, there is one photo that stands out and pressures the viewer to forget about the faces and ideology clouding the revolution. One of Korda’s photographs, La Nina de la Muneca de Palo, would better serve as the face of the movement. A young girl grasping a wooden stub dressed in white fabric like a doll of an indistinguishable gender conjures a figure between a woman dressed in a beautiful white dress or a man in a starched straightjacket; both the tragedies of the revolution. This historic record serves as a reminder of the decline of the wealthy and the blistering insanity of Che’s radical approach.

Among this shot, there are others showing the elderly struggle and the young men raising AK47, the last of which display never before seen photographs of a cold blooded and dead Che. The exhibit is organized chronologically, with photos strategically introducing details that foster the reality of each subsequent shot. Appropriately, viewers are reminded of the historical nature of this exhibit and the fundamental significance of photos as a historic medium, in general.

November 9, 2010 No Comments