African Art, New York, and The Avant-Garde

“My little brother could sculpt something better” says a Met visitor, after their first time seeing African art in person. It is a common misconception to think that African art is primitive. However, the use of over-exaggerated proportions and geometric shapes that deviate from the organic curves found in nature and in the body are characteristic of a sophisticated style. Modern art forms, such as cubism and expressionism, have emerged, drawing from these elements which are particularly found in African sculpture from Kota, Igbo and Fang artists. The exhibit featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, entitled African Art, New York and the Avant-Garde, intends to demonstrate just that.

The exhibit, a condensed space displaying mostly sculptures, is predominantly African art. Next to many of the African pieces (or somewhere in the vicinity), there is a Modern Art piece and descriptions to highlight the similarities, but the modern works selected did not contain enough visual evidence to demonstrate the influence. The description cards for most pieces described how theparticular piece was a muse for late 19th and 20th century art, but there was too much “tell” and not enough “show.” Visual examples, like cubism pieces, would have conveyed this theme in a more coherent—and interesting—manner.

The exhibit, a condensed space displaying mostly sculptures, is predominantly African art. Next to many of the African pieces (or somewhere in the vicinity), there is a Modern Art piece and descriptions to highlight the similarities, but the modern works selected did not contain enough visual evidence to demonstrate the influence. The description cards for most pieces described how theparticular piece was a muse for late 19th and 20th century art, but there was too much “tell” and not enough “show.” Visual examples, like cubism pieces, would have conveyed this theme in a more coherent—and interesting—manner.

Although the exhibit lacked a strong theme, the individual pieces were quite beautiful and their descriptions offered an insight into their respective cultures. A mask piece captures a sophistication in its composition: bulbous oval eyes, a wide triangular nose and curvaceous lips carved out of wood are typical of the geometric style that was often embraced by this culture. The mask adjacent to it has contrasting proportions: a narrowjaw line, two slits for eyes, a skinny cylindrical nose and a mouth in the shape of a small “o”. The masks somewhat resemble caricatures, and are mostly made of wood. What is especially fascinating is the fact that the different regions produce their own unique portrayals of facial features, yet the theme of the geometric style can be identified in probably all African masks. One piece, entitled Mask (Kpeliye’e), which according to the description, is a “delicate, feminine representation that honors deceased Senufo elders,” has an array of textures created by etched lines. Environmental influence is present, especially in the goat horns on its head and the small, exposed teeth.

Matisse: In Search of True Painting

The Metropolitan Museum of Art features another exhibit emphasizing style: the well-known fauvism painter, Henri Matisse struggles to find his artistic voice. This space is significantly larger than the African Art space, and palpably more crowded. It is plain to see why: the comparisons here are much more successful in threading together a common theme because it shows several versions of the same painting side by side. This exhibit was much more interesting and enlightening because it shows his process; each version, although portraying the same subject, demonstrates how different styles create such varied experiences.

metmuseum.org

metmuseum.org

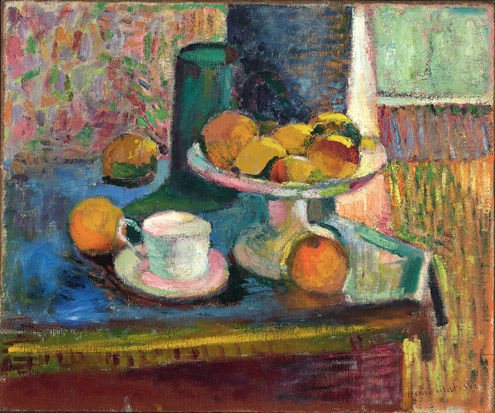

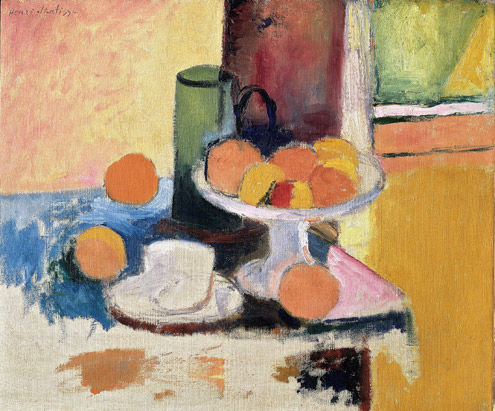

A wall on the right upon entering displays a panoply of four small paintings, all of a bowl of fruit. On the far left, Matisse dips into pointillism, a painting style that is achieved by marking thousands of small colored dots of paint on the page. Darker, condensed dots create shadowsandlighter, spaced dots create the illusion of highlights. The dots form together to create the bigger picture. Another bowl of fruit painting in the series is an experimentation with impressionism, as he uses thick blotches of paint to bring out the strokes and variety of color. Entitled Still Life With Compote, Apples and oranges (1899), this piece was painted with bright, saturated colors and many vibrant strokes full of motion. Although oil paints were used, the consistency makes it look as if it were drawn with oil pastels. The lines seem to move in all different directions, giving it a sense of urgency or chaos. This tone is strikingly different from the piece next to it, again of the same subject. It is unfinished: Matisse leaves a part of the canvas naked, with exposed pencil markings. Other works in the exhibit follow this practice of ‘unfinished canvas,’ which offers yet another look into the artist’s process and decision to keep moving on to create new works, and not going back to finish the others. Because Matisse has embraced so many different styles, he was accused of ‘copying’ his counterparts like Van Gogh and Monet. He was inspired by these artists as well as Cezanne,

metmuseum.org

metmuseum.org

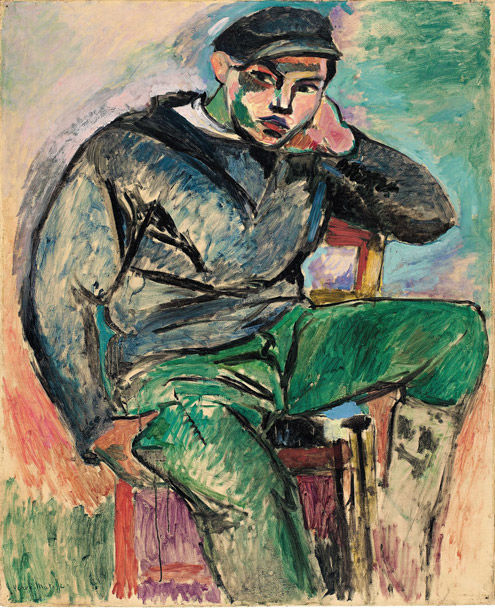

Young Sailor I and Young Sailor II are two versions of the same subject, and again, are quite different. While the latter resembles a pop art style with ‘paper cut-out’ bright blocks of color, the former is a painterly piece with heavy outlines, a sense of depth and a more diverse palette. Interestingly enough, both the body language and facial expressions differ in each version: the former features a young man in deep thought, with relaxed limbs and an air of confidence. An up-tight pose, bright eyes and a simple palette are qualities of the other version. The pencil markings make quite a presence in Young Sailor I, underneath a thin layer of paint with some spots of bare canvas. Both pieces were made in 1906. Young Sailor II has slight indications that Matisse might have been inspired by the African Masks: The boys face is not proportional, but instead characterized by geometric facial features and is painted in a way that creates a directional line texture, which is found in a lot of the masks.

Why is the exhibit called In Search of True Painitng? The exhibit does a flawless job in displaying that this artist had a desire to document the stages of his work and try on different methods. In other words, he constantly compared his works to see if he advanced or regressed. He left pieces unfinished because he intended to use them as a reference point. The entire exhibit maps out his quest to find his visual personality as an artist through the process, not the product.

Great comments on Matisse. Especially notable –your last paragraph!