Diljit Singh

Often when one speaks of a genius the public tends to associate with them a cloud of isolation (even more so when the subject is not only a genius but a prodigy). While people such as Franz Kafka and J. D. Salinger or on the mathematical spectrum Gauss and (the crowning example) Grothendieck do very well exist, so do people such as Mozart, Terrance Tao and Paul Erdos. Those in the latter group lived holding communication in very high esteem. It is through the evaluation of letters that a great deal is known of some of these geniuses. Focusing on letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart the artist is revealed to be a rather loving yet manipulative person, well able to relate to those he wrote to. The time frame and subject matter of the letters go even further beyond connections with others leaking into subjects such as finance and time management.

It does not take long to grasp the feelings Mozart expresses to those close to him. He uses a varied set of expressions when addressing, amongst others, his wife and father. For insistence Mozart wrote, “[if you do not get better] I can come with all human speed to your arms!” when speaking to his father while he told his wife that when ever he is confronted with an image of her he begins to weep. (Letters 109 and 115 respectfully). These instances of hyperbole were no coincidence, you would be hard pressed to find a letter where the dramatic musician did not excessively exaggerate on the topic at hand, whether it be love or work. Straying to friendship, Letter 119 reveals the strong relationship Mozart shared with Michael von Puchberg, whom Mozart often referred to as a brother. Mozarts great success in cultivating this relationship is illustrated when Puchberg time and time again lent money to help pick Mozart up from crippling debt.

On the topic of debt, it is impossible to evaluate Mozart on a personal level without taking this, unfortunate, massive issue into consideration. Mozart often found himself without enough money and this issue stemmed from a number of sources ranging from having to compose for royalty, free of charge, to overspending. It is through out these letters the readers gets to witness Mozart in a cunning and manipulative manner. Mozart would acquire debt and use a number of rhetorical devices (usually pathos, in addition to his excessive and frequent exaggerations) to guilt his way into money. A glaring example of this is when Mozart writes (to Puchberg), “And if you, my best friend and brother, forsake me, I unfortunate and blameless, and my poor sick wife and child, are all lost together!” (Letter 118).

Though Mozart’s short life was one riddled with financial woes and periods of distance from those he loved, the artist spent a considerable amount of time doing what he loved. Music was more than a hobby it was his life. The brevity of some of Mozart’s letters can attest to the priority he placed on his passion. In a few letters (e.g. 107) Mozart even states that time is highly scarce for him. However this passion of his soon transformed to work, when he was met with crippling debt and that is when Mozart transformed from an entertainer to a worker. From someone whose primary objective is playing and money is a consequence to the converse.

Author Archives: diljitsingh

Looking at Art (Diljit Singh)

The word homomorphism is, by convention, one reserved for mathematics. If after taking a set, A, and performing some transformation, T, you get, B. If A and B behave similarly the two are referred to as homomorphic. A trisection of sorts, art too can be broken into A, B, and T.

The first part, A, is the inspiration: the mountain view, the beautiful flowers, the rich in-your-face colors. Now this is the reason the artist does what he or she does. This aspect of art has more or less remained constant. The setting was always our world, our imagination, and our thoughts.

While it is true that art has been through a number of periods, each characterized by particular a focus it is important to note that this due heavily to the lens of the the artist. This is the transformation, where the artist really experiences a setting where the shapes come alive and where smells meld together. The artist decides what he wants to convey and he puts it on a his metaphorical canvas. Alice Chase covers what exactly it means for an artist to experience a setting, in her book Looking at Art. Chase starts with an example from ancient Egypt, she refers to a painting which can in some senses be called discrete. It gives more of a map of the setting as a whole, one which lets the viewer distinctly identify every part of the image. Fast forward to the 1500’s and Chinese Art starts to incorporate God. Jumping from the “maps” before, things such as rocks become characterized by simple brush strokes. Paintings also lacked color variation and had white spaces used to stir feelings of daydreaming. Medieval artist in Europe also focused on God, oftentimes downplaying the emotions of man, all the while depicting everyday life. Skipping forward 200 years we arrive at doorstep of the Dutch. Looking around us we see a beautiful world. The Dutch focused, in the 17th century, on their landscape. These paintings started out rather intimate highlighting a number of aspects the artist felt. Soon this process was streamlined by conception of a formulaic “landscape” design. Soon artist left became more focused on the personal aspect. They injected their thoughts more predominantly in their art. Vincent van Gogh is a glaring example of this personalization as is noted in a number of paintings, most popular possibly being A Starry Night.

The transition from a pictorial map to highly personal and intimate art was (and still is) a growing process which (as seen through the last paragraph) took many many hundreds of years. Early Egyptians did play with angle and try to better articulate their feelings, but this was difficult to do during that time. This issue became less and less a dominating problem with the addition of aspects such as shadow, depth, and atmosphere coming into play.

The last element of an homomorphism is B, the viewer. The viewer may have the painting simply because his friends do. As was the case in the early 19th century amongst Englishmen. Or in the case of the United States before the 18th century: landscape paintings were not popular. The audience in the U.S. had enough outdoors to worry about as it was. This mindset of the American audience changed as time passed and the land became more developed. Particularly however, Chase highlights the notion of perception when she refers to Livia, a Roman Empress, who immersed herself in art. For her, realistic paintings of the outdoor put spawned her a new world, she was in the art. This deep connection may not always be reached but is definitely remains the goal.

Now how are A and B similar? Given any setting we can construct a perception. Likewise, given any perception we can along with the originator we can trace it back to a set of feelings, thoughts, or experiences – a setting. All that is required is an “Artist,” whatever that is…

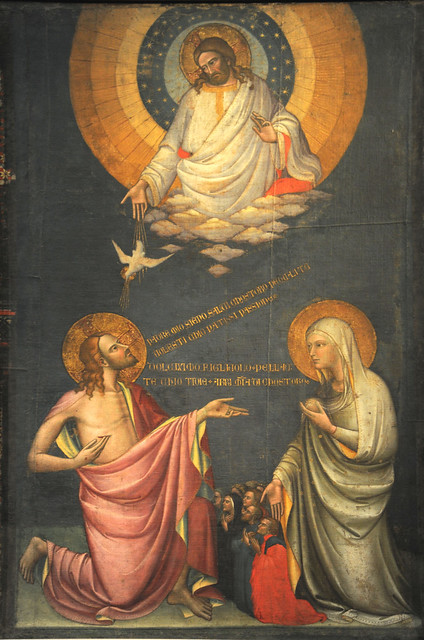

The Intersection of Christ and The Virgin Lorenzo Monaco

With this very Body

I have fed thee,

Dearest Son of Mine.

On that merit

I beseech thee for pardoning.

Not toward me

But to those who have caused

My Dearest Child great Pains.

Ingrained in my chest is

a mark.

Mother, I have not forgotten

that pain, that suffering

bestowed upon me.

But have you forgotten why I suffer?

I suffer because I have loved.

There is no one whose soul

escapes the reaches for

redemption, the power of

my Father.

I send you, great child of Mine

A Dove, in lay the Holy Spirit.

My son I shall have mercy if

That is what you wish.