Neighborhood residents-url

From The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

East Harlem Residents

Racial Breakdown

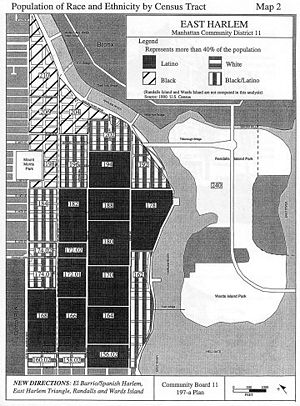

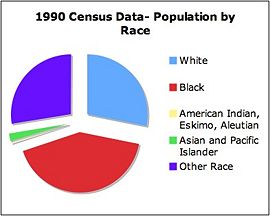

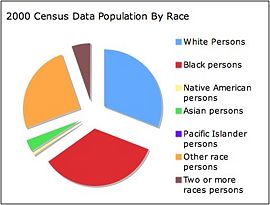

The population of East Harlem has increased by 6.5% from 1990 to 2000. However, the breakdown of the population into individual races has changed significantly. The number of whites has increased due to gentrification as can be seen in the pie chart. Furthermore, the percentage of blacks in the total population has decreased. The Hispanic population, which isincluded in the "Other Race" section of the pie chart, has increased somewhat. As opposed to a change in number, there has been a greater change in the type of Hispanics in East Harlem in the past decade.A 1990 census map, by race, of East Harlem as documented by its Community Board No.11. It shows the drastically Latino population of the majority of East Harlem (north of 96th Street and east of 5th Avenue). The central majority of the neighborhood is Latino, surrounded by pockets labeled "Black/Latino." Blacks are the next largest population. There are only two small districts, immediately north of 96th Street (as close to the Upper East Side as possible) that are labeled "white." This is a fairly accurate portrayal of the racial breakdown of East Harlem, as the proportional representation of races have not changed dramatically in the past decade.

Racial Breakdown: East Harlem vs. The Upper East Side

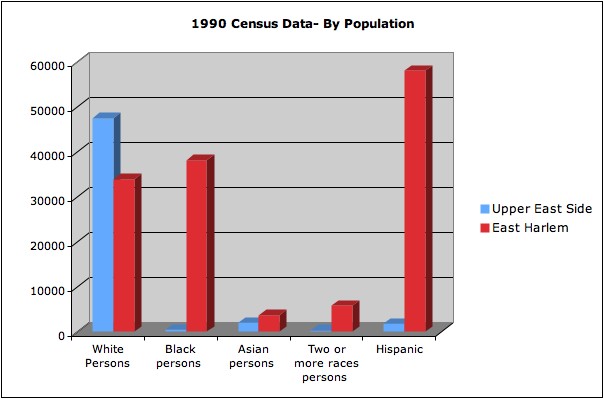

This 1990 U.S. Census-based graph is perhaps the accurate depiction of the radical racial difference in the populations of the wealthy Upper East Side (below 96th Street) and East Harlem (above 96th Street). Foremost, the Upper East Side has many more white residents than East Harlem. Equally noticeable is the practically nonexistant black, Hispanic, Asian, and multiracial populations of the Upper East Side, whereas they are the vast majority in East Harlem. Also, because the graph compares numbers and not percentages, one can easily see that East Harlem has many more residents than its neighboring community, though their geographical areas are roughly similar in size — the wealthy Upper East Siders have much more area per person than the residents of East Harlem.

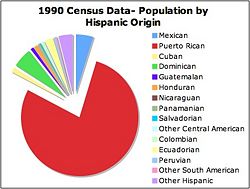

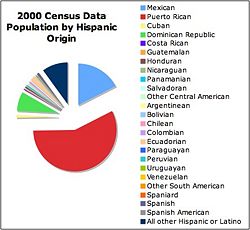

Hispanic Population

The Hispanic population has increased by 6.9% from 1990 to 2000, which is consistent with the overall population change from 1990 to 2000 (6.5%). However, the countries of origin of the Hispanic population have changed drastically. The Puerto Rican population continues to dominate East Harlem, but has decreased in percentage significantly. At the same time, there has been an influx of Mexicans in the last 10 years, increasing from 2,450 to 10,209. These are the newest immigrants to this area. Additionally, there has been increased immigration from Latino countries that did not have high immigration rates in 1990.

Demographics of East Harlem

East Harlem (1990)

| East Harlem (2000)

| Upper East Side (2000)

| |

| Population | 102,248

| 108,092

| 216,441

|

| Largest Age Group | 25 to 34 (18.1%)

| 25 to 34 (15.6%)

| 25 to 34 (24.8%)

|

| Male-to-Female Ratio | 44.8% to 55.2%

| 47.5% to 52.5%

| 44.7% to 55.3%

|

| Never Married (15+ years old) | 34.8%

| 45.5%

| 42.4%

|

| Now Married (15+ years old) | 18.4%

| 30.9%

| 42.0%

|

| Family Households (Single Parent) | N/A

| 64.4%

| 16.3%

|

| Family Households with Single Male Head | N/A

| 15.4%

| 23.4%

|

| Family Households with Single Female Head | N/A

| 84.6%

| 76.6%

|

| Hispanic Residents | 51.7%

| 55.3%

| 6.1%

|

| Non-Hispanic Black Residents | 33.3%

| 33.3%

| 3.3%

|

| Non-Hispanic White Residents | 12.6%

| 25.0%

| 82.4%

|

| Asian Residents | 1.8%

| 2.7%

| 6.4%

|

| Foreign Born | 11.0%

| 21.3%

| 21.5%

|

| No High School Diploma (25+ years old) | 48.0%

| 46.0%

| 5.0%

|

| Bachelor's Degree or Higher (25+ years old) | 19.0%

| 12.7%

| 74.3%

|

| Unemployed (16+ years old) | 16.0%

| 17.7%

| 3.7%

|

| Median Family Household Income | $18,803

| $23,211

| $136,872

|

| Per Capita Income | $11,417

| $17,740

| $126,091

|

| Poverty | 37%

| 38.2%

| 6.6%

|

| Median Gross Rent | $429

| $442

| $1,217

|

| Births | 2,202

| 1,725

| 1,019

|

| Deaths | 1,239

| 1,791

| 582

|

| Leading Cause of Death | cardiovascular disease

| cardiovascular disease

| cardiovascular disease

|

| New Cases of AIDS | 413

| 140

| 12

|

This table depicts the demographics for East Harlem in the past (based on 1990 US Census information), East Harlem in the present (based on 2000 US Census information), and the Upper East Side in the present (based on 2000 US Census information). This chart provides points of comparison on the evolution of the East Harlem neighborhood over a decade and also contrasts the neighborhood and its residents to the Upper East Side and its residents. It is important to note the significant distinctions between these two neighborhoods regarding their respective ethnic make-ups, the nature of their family households, the extent of education of their residents and what that means in terms of their employment and incomes. The juxtaposition of these figures and statistics in this table highlights how extreme East Harlem and the Upper East Side are, and emphasizes how well off Upper East Side New Yorkers are compared to their East Harlem counterparts just above East 96th Street.

Interracial Relations in East Harlem

Past (1990 and Before)

This section covers interethnic (and in some cases intraethnic) relationships in East Harlem in the 1990s and before. The most prevalent of these interethnic relationships has been the tension between Puerto Ricans and African Americans. However, since much of this overlaps with the present, I won't go talk too much about it. I will only say that these conflicts arose from the concerns that Puerto Ricans had about this cultural identity associated with East Harlem. They feared that if other ethnic groups started to move into East Harlem, it would have lost its identity as "Spanish Harlem" or "El Barrio". According to Russell Sharman, Puerto Ricans moved into East Harlem during the early 1900s, (c.1917) making them the predominant ethnic group after Italian and Jewish Americans. So it would seem natural that Puerto Ricans would want to defend East Harlem from outsiders. According to Arlene Davila, author of Barrio Dreams, Puerto Ricans have viewed East Harlem as the Hispanic capital of America.

Apart from African Americans, Puerto Ricans have also clashed with Mexicans for pretty much the same reason. While this tension has sometimes manifested itself into violence (as witnessed by Maria in a chapter of Sharman's book), the most evident of these clashes has been over "El Museo del Barrio". Since its inception in 1969, "El Museo" has catered exclusively to Puerto Rican art. In 1977, however, "El Museo" has expanded its collection to include art from across Latin America. Once again, Puerto Americans were scared that such a change could dilute the influence of a Puerto Rican presence in East Harlem. Because of this, the Puerto Rican community has met this change in "El Museo" with some resistance. The role of the Mexican people comes into play later on. However, since it overlaps into the present, I won't go into too much detail. Despite this resistance, some Puerto Ricans have embraced the idea of a pan-ethnic Spanish Harlem, such as Jose, a Puerto Rican man who is mentioned in Sharman's book. According to Jose, even if more Mexicans move into East Harlem, it will still be known as "Spanish Harlem", albeit more diverse Spanish Harlem, but a Spanish Harlem nonetheless. It is interesting, however, that Puerto Ricans would create tensions with people that speak their language. What is even more intriguing is that there exists some racialization within Puerto Ricans. According to Russell Sharman, this can be somewhat explained through differences in skin complexion. Apparently there is some hierarchy within the Puerto Rican community where light-skinned Puerto Ricans view themselves superior to darker-skinned Puerto Ricans. Mothers would tell their daughters to marry light-skinned Puerto Ricans to "improve the hair of the race".

One last note is the role of white people in these interethnic relations. There is, of course, the age old struggle between African Americans and Caucasian people, beginning ever since African Americans migrated from the South. We also see this tension between Puerto Ricans and Caucasians. According to a New York Times article published in 1992, white people create this stigma between themselves and Puerto Ricans, viewing Puerto Ricans as "inferior" as well as harboring their own misconception about Puerto Ricans. In this article, a 14-year old girl called Lydia Jerez, retells of her encounter with racism as she was coming home from school. Lydia was riding in a bus when a elderly white woman demanded her seat. After Lydia relinquished her seat, she overheard the woman telling a white student seated beside her, "Those Puerto Ricans don't have respect for nobody." However, Lydia wasn't the only one affected by this racism. A 20-year old man by the name of Miguel Ortiz recounted his experience with racism that occured in his high school honors biology class. One of his colleagues, a white student, received a higher score than him on a paper. The white student then proceeded to patronize Miguel and claimed that he was a better student on the basis that he was "white". Despite this unfavorable encounter, Miguel worked his hardest and eventually surpassed the white student. To see whether or not these interethnic relationships have been ameliorated, one must look to the present. (2000 and after)

Present (Past 10 Years)

In the more recent years, the interracial relations in East Harlem don’t seem to have changed much. They have become somewhat less prevalent in everyday life, perhaps, yet they are still obviously present. There is still an ongoing competition between Puerto-Ricans and African-Americans, as well as one within the Spanish speaking groups – Puerto-Ricans, Mexicans, Dominicans, etc. There is also much racism, both within these groups as well as with Whites.

Though the crime rate in East Harlem has decreased drastically over the years, it is still higher than average, and often considered a dangerous area. There are many crimes that have been reported in East Harlem, of which many are considered “hate crimes.” On April 1, 2006, Broderick J. Hehman was chased into the roads of 125th Street and hit by a car. Four black Harlem teenagers (ages 13 and 15) were arrested and charged with his murder, as well as robbery. One of the attackers was heard by an anonymous witness as he yelled, “Get the white guy!” However, Deputy Inspector Michael Osgood, the commanding officer of the Police Department’s Hate Crimes Unit, stated that “although one of the attackers may have used racist language during the chase, that in itself did not make the incident a bias crime” (New York Times) This is not to say, nonetheless, that there was not a higher chance of these teens choosing Hehman as a target simply because of his skin color. ([1])

There have been many other issues concerning races and racism in East Harlem over the past few years. In a New York Times article published on May 21, 1998 ([2]), “The Reverend Calvin O. Butts 3d, a prominent Baptist minister from Harlem, stunned city officials and black leaders alike yesterday by calling Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani a racist who is on the verge of creating a fascist state in New York City.” There are some obvious cases of racial profiling within East Harlem, of which Butts offered some examples.

The tensions of racism are not only presented in everyday life, but in creative ways as well. Pepon Osorio, an artist with creations in the Young World Store on Third Avenue in East Harlem, uses his art to address issues of racism and identity. His art frequently deals with racism against and among Latinos (New York Times). As the demographics of East Harlem shift, so do the tensions between the different racial groups. It seems as if there will always be a competition between the largest groups of the area –each group fights to surpass the other, in a fight to be fairly represented.