From The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

The Alliance

Kat Mateo * Marlen Herrera-Rojas * Annie Tran * Jasim Uddin

The D Meets the Stadium

What Our Focus Will Be

Our group will be covering the time period during which the Bronx was undergoing fundamental physical and social changes, the 50s and the 60s. We will mostly look at the importance of the B/D train line in the South Bronx as well as its connection to the Yankee Stadium, the building of the Cross Bronx Expressway, and other changes instituted by Robert Moses.

The Locomotive and the Bronx

The institution that we will be focusing on is the city-owned subway Independent B/D line under the Grand Concourse, which was constructed in 1930. Its service began on December 15, 1940 when the IND Sixth Avenue Line opened. Its creation, back in the day, symbolized the growth of the Bronx in the midst of prosperity and the need to control and accommodate this growth. Rapid transportation was the bridge between the Bronx and Manhattan and was designed to provide an affordable means for commuters to travel between the boroughs on a daily basis. Ironically enough, though transportation was built in response to growth and prosperity, the settlements in proximity to these convenient tracks tend to be of lower income groups.

Institution Research

In 1900, the city agreed to finance the transit system but would only lease it to a private corporation. The subways came to the Bronx after compromising between transit interests and the city. This compromise led to the construction of two subways lines in 1905. One subway line was the extension of the Broadway line that passed through upper Manhattan before entering northwest Bronx Kingsbridge (the current 1 and 9 trains). The other subway line entered the Bronx at 149th Street and to West Farms (the current 2 train). Because there was a demand for more transit lines to relieve congestion in Manhattan, the 4 and the 6 transit lines were created. In 1930, the transit company convinced the city government to allow the construction of the only fully underground subway in the Bronx. It was to be owned by the city and was known as the Independent D line.

This subway line, like many others, increased land values and building activity. This led to urban development. There was an increase of population along the D line. The increased number of transit lines led to more businesses, institutions, and public works, which bettered the economy of the Bronx. Places such as the Bronx Zoo, Yankees Stadium, NY Botanical Garden and Fordham Road were located near the D train for this reason. Many people depended on the trains to get to work.

On the first of July, 1933, the city-built IND subway, with intervals along Grand Concourse, opened its doors. With the new subway line and affordable commute to Manhattan, the value of real estate escalated. Before this new development, much of the Bronx was occupied by Victorian houses with front porches and lawns, and though many of these homes still remained, many more large apartment buildings decorated with gargoyles and courtyards towered above the streets. As a result Grand Concourse became a desirable residential area and the area just beyond the Concourse Plaza Hotel was housed businessmen, judges, and professionals.

Rapid transit trains did not just act as a means of commute for workers; they also provided a gateway cultural mingling and recreational possibilities. Upon our visit to the New York Transit Museum, a nifty institution that appeared convincingly like a real subway station, we interviewed a MTA worker, William Byrines, who spoke vaguely about the numerous changes made to transit lines over the years and chuckled, “just use your common sense,” when asked about the impact that the IND line had on the people. He then elaborated, “Well I took the D to 161st for the Yankee games, so I was happy.” Every day a ‘trail mix’ of people mingled among one another to await their station stops and during this temporary commingling period, even when one did not take initiatives for conversation, one can witness and absorb many of the various exotic cultures existent in New York.

In the 1960s the subway stations, especially during the late night hours, allowed many discontented pedestrians to grouse with one another about the harsh economy, and for panhandlers to a few decent bucks. As Mary, a twenty-five years old woman with four children, admitted in the New York Times article To Night People, the Subways are many Things, “Last Friday was a good night, I made 30 dollars.” The trains were also morphed forms of art that featured graffiti pictures complete with snide comments. As demonstrated in the 2001 Submerged MTA artwork, the subways are both an organism for and product of cultural diversity.

Primary Sources

New York Times article, "To Night People, the Subways are Many Things"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Highlights of Program for Subway, Rail and Air"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

Narrative of the South Bronx Development During the 1950s and 1960s

During the post world war period, the South Bronx no longer met the middle class expectations as it once had in the early nineteen twenties and thirties. The neighborhood, however, retained its Irish, Jewish and pockets of Italian ethnic groups in the South Bronx. During the 1950s, the South Bronx was becoming more crowded, as newer groups started moving in. These new groups included the Puerto Ricans who began immigrating to New York as early as the late 1940’s. By 1953, the Puerto Rican immigration hit an all time high of fifty-two thousand, thus bringing the total number of Puerto Ricans close to half a million. People from Spanish Harlem started moved on northward to the South Bronx. Another group of people entering the South Bronx were the African-Americans who were moving to New York city from the South and to the Bronx from nearby Harlem. By 1950, there were about 160,000 African-Americans and Puerto Ricans in the Bronx alone and 91 percent resided in the South Bronx. Many Jewish and Irish residents began moving out of many of these neighborhoods. African Americans dominated most of Morrisania and Puerto Ricans were mostly concentrated in Mott Haven and Hunts Point.

During the post war period, a great housing crunch affected the housing market nationwide. Returning war veterans looked for places to start their lives again. Thanks to federal policies like the GI Bill and mortgage guarantees, home ownership came within the reach of more Americans than ever before. Most of these new homes were located in the suburbs, some of which (like Levittown) discriminated against African Americans and other racial minorities. Many middle class Jews and Irish began to move out of the South Bronx to places like Levittown, Long Island, upstate New York, and to Riverdale and other parts of the Northern Bronx. This “white flight” was marked throughout the 1950s all across the nation. The new incoming groups such as Puerto Ricans and African-Americans soon filled the vacant dwindling residences in the South Bronx. However, public housing stilled remained a problem for the city. By late 1950s, under the coordination of Robert Moses, New York City completed 20 housing projects and had at least 15 that underwent construction. During this period, the city was undergoing its slum clearance programs under the 1949 Housing Act. Many slums in Lower Manhattan had been cleared, forcing people to head north and into the already crowded South Bronx. The new demolition occurring in Harlem and East Harlem also forced residents to move north to the South Bronx. As public housing arrived in the South Bronx, people again had to move. Many of these slums consisted of minority groups such as blacks and Puerto Ricans. These groups of minorities filled many of these low-income houses. As more minorities entered the slums of the South Bronx, many middle class whites fled the city for better housing conditions in the suburbs. Fearing the mass exodus of “the white middle class,” the city began building housing projects that were exclusively for the middle class. Many white Jewish residents on the Grand Concourse moved to Co-op City, a high-rise apartment complex, which was completed in the late 1960s. Luxury-housing complexes were being built in South Bronx as well, such as Concourse Village, which was south of 161 St and Morris Ave. However, Hispanic bodegas began to replace the Jewish delicatessens and Spanish films began to play at local movie theaters. Rent control and scarce housing were among the many reasons why many of these minority groups stayed. There were pockets of Jews around Intervale Ave in Hunts Point - Crotona Park East where there was a synagogue, some Italians near the Church of Our Lady of Pity in southern Melrose, and some Irish nearby St. Jerome church in Mott Haven.

Despite these changes, the national economy was booming during the postwar period. Prices during the 1950s and early 1960s stayed relatively stable. Also during the post war period, job opportunities increased and so did people's wages. This allowed many Americans to be able afford merchandise such as a telephone and the newly invented televisions. Many stores along Tremont Ave, Third Avenue (The Hub) and Webster Ave (near Fordham Road) allowed installment payments, which allowed many Bronx families to buy furniture or other expensive products without first saving large sums. This allowed shoppers to make small monthly payments that included a low rate interest payment. Televisions dramatically changed the lifestyles of many Bronxites. Many popular shows took place in the Bronx such as The Goldbergs and The Toast of Town, which took place in the Tremont neighborhood. This brought entertainment into the home, which caused the number street singers to disappear by the mid 1950s. People continued to shop around 149 St. and Third Ave (The Hub) like their predecessors.

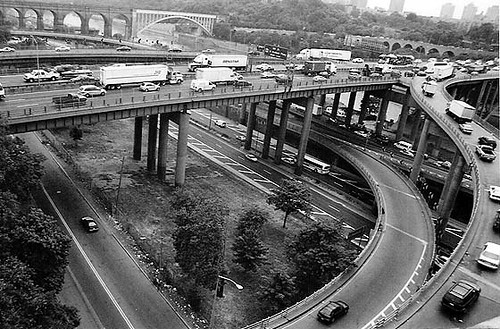

The most dramatic impact on the South Bronx was Robert Moses creation of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, which was approved in 1944, which cut through the heart of the Bronx. The building of the expressway sliced through a dozen solid, settled, densely populated neighborhoods in the western portion of the Bronx. Blocks of apartments had to be destroyed at a time of a housing crisis. The neighborhoods destroyed were not actually slums. They had housing that was better and newer than the ones in Mott Haven, Melrose, Morrisania-Claremont, and Hunts Point-Crotona Park East. The city ignored protest from the residents of East Tremont, and by 1955, all the occupants were evicted. Houses that were near the expressway became less desirable. The Cross Bronx Expressway did serve as an improvement for transportation for travelers, but it did it at the cost of the destruction of East Tremont neighborhood and other neighborhoods as well.

The sense of decay of the South Bronx began to emerge in the mid and late 1960s. As more minorities began to enter the South Bronx, the living conditions worsened. Poverty began to rise. Wherever, there was poverty, gangs and violence emerged. New York City during this time was engulfed in a massive wave of crime and public disorder, which was characterized, by the murders, muggings, rape, burglaries, and car thefts. Drug addiction began to rise. New gangs emerged during this era. The majority of all the crimes in the Bronx occurred in the South Bronx. This sense of disorder continued to worsen which would plague the South Bronx well into the 1970s.

Works Cited

Gonzalez, Evelyn, The Bronx, New York, Columbia University Press, 2004

Hermalyn, Gary and Ultan, Lloyd, The Bronx It Was Only Yesterday 1935 – 1965, New York, The Bronx County Historical Society, 1992

Jones, Jill, South Bronx Rising, New York, Fordham University Press, 2002

New York Times article, "Cross Bronx Expressway Bid"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Tunnel and Ramps to Speed Traffic"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Moses Threatens to Halt Bronx Job"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Lyons Gives Reply to ‘Pooh-Bah’ Moses"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Bronx Expressway Route Approved To ‘Demagogue,’ ‘Blackmail’ Cries"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

New York Times article, "Bronx Terminal Market Hailed by Produce Farmers and Dealers"

Obtained through the Lehman College database.

Thank you for stopping by and...