Christianity

From Seminar 2: The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

West Indian Churches in New York

West Indian Christianity is a crucial part of lives of immigrants in New York. West Indian churches serve the purpose of revitalizing the migrant’s cultural needs, as well as finding spiritual and secular consultation for his or her difficulties in adapting to the new environment (Kiev 129). The informal environment created by singing, music incorporating drums, tambourines, and keyboard (as opposed to a church organ), and audience participation all work to reinforce West Indian culture (Hill 118). In belonging to such a community, an immigrant is equipped with security and solidarity.

The Formation of Afro-Caribbean Religions

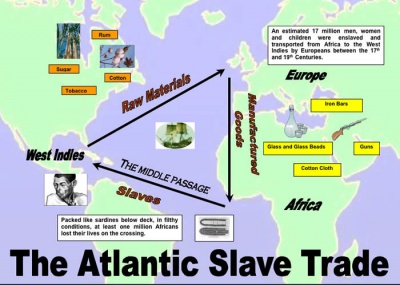

The West Indian islands became heavily populated because of the heavy slave trade into that area starting in the early 1600’s. Slaves would be packed in cramped, dirty, and unsafe hulls of ships and usually send to word on large plantations from Africa. Although they had a hard time getting to the West Indies and surviving servitude, some elements of African culture were still preserved. “Indigenous African religious ideas, however, did survive the difficulties of estate life…In the Caribbean, however, African religious ideas were to undergo significant changes but they remained recognizably ‘African’ in structure.” (Sankeralli, 51). These changes occurred because of the circumstances of plantation life and the fact that African religions were looked down upon by plantation owners. Europeans thought that their ideas and religious practices were superior to anyone else’s. They viewed the African culture as inferior and demonic (Sankeralli, 54). “The European slave holders were in particular afraid of African drums and so-called ‘magic’ because they believed that drums were a mode of communication” (Schmidt, 237). These unholy rituals had to be replaced by European Christianity.History of Caribbean Churches

According to Robert Worthington Smith, the history of West Indian Christianity started when the West Indies became an important economic commodity to the British Empire due to the Atlantic Slave Trade. The slaves, transported from Africa, were targets of Christian missionaries. Many Englishman blamed their “licentious sexual habits” and poor maternal care that were causing infertility in slave women (Smith 176). The barrenness in the women was hindering the self-reproduction of the slave population. Although it was actually the brutal condition of slavery that induced the high rates of infant mortality, abortions, and miscarriages, many Englishman took up the opportunity to Christianize the slaves (Smith 176).

When the English made an earnest missionary effort in 1823, many non-Anglican Churches had sprouted to fill the vacuum (Smith 173). Protestant sects, such as Moravian, Methodist, and Baptists, were greatly inspired by the Great Awakening in the 1740s (Mitchell 25). These missionaries offered an alternative to the conservative Anglican Church by encouraging greater audience participation and singing. Baptist Missionary Society in 1814, and the Methodist Missionary Society in 1789 were just two of the many non-sectarian missionaries established in the Caribbean (Smith 174).

Syncretism

Although missionary groups came to the West Indies to Christianize the population and exterminate the “savage” beliefs of their African roots, the West Indies had developed many religions on their own. The Afro-Caribbean religions incorporated many different religious elements from Africa, Europe and the indigenous Native Americans (Schmidt, 236). The fusion of diverse religious practices can be called syncretism. To some “syncretism” can have a negative meaning, because according to a Christian meeting in Tambaram in 1938, syncretism was an “ ‘illegal mingling of different religious elements’ ” (Sankeralli, 32) . However, syncretism was a natural phenomena as African religion was banded in the Caribbean and people had to adapt to the ways of the colonists. One example of this would be how in African religion there are many religious deities, which made it possible for them to also praise Catholic religious saints (Schmidt, 237).Afro-Caribbean religions offered resistance against slavery, invoked their African Gods (such as Ogun and Shango) and reinterpreted native folklore. Revivalism and nativism were two ways in which the new Afro-Caribbean religions defined themselves. An example of how Christian elements and African beliefs mixed it Haitian Vodoo religion. African saints were identified with Catholic saints and incorporated crucifixes, rosaries, and holy water. This supports the idea that “The African peoples not only absorbed Catholic beliefs and practices into their African religious practices, beliefs, and traditions, but also Africanized Protestant branches of Christianity” (Sankeralli, 32). It was hard to pull away African culture from the religion of the African slave population in the Caribbean.

Religious rituals were at the heart of religion, because it determined how worship was carried out. For some West Indian religions, the separation between the Afro-Caribbean religion and European religion was the ritual change. An example of this change in ritual due to the culture of the land was the set up of a Spiritual Baptist church. With the Christian symbols in the front of the church and Hindu and Islamic paraphernalia in the back, the blending of culture and different religions was a typical example of West Indian religion. (Glazier, 52). These various syncretism religions of the West Indies carried over to America as migration started.

Two Perspectives on Church

The focus of our study delved into two different aspects of West Indian Christianity. One perspective research was understanding the Development of West Indian religion abroad, which looks at the ways in which missionary efforts to countries of the ethnic origin aid in deeper understanding of identity. Another facet of West Indian Christianity that was observed was Christian Church as an Immigrant Association that observed how West Indian churches in New York, in specific Brooklyn, functioned as both a religious group, while sharing characteristics of an immigrant association.

Works Cited

- 1 http://www.freefoto.com/images/05/08/05_08_11---Three-Crosses_web.jpg?&k=Three+Crosses

- 2 http://www.irespect.net/images/SlaveTradeMap.jpg

- 3 http://farm1.static.flickr.com/64/202209634_166628ff8f.jpg?v=0

- Glazier, Stephen D. “Syncretism and Seperation Ritual Change in an Afro-Caribbean Faith.” American Folklore Society Vol. 98, No. 387 (1985):pp 49-62

- Hill, Clifford. "From Church to Sect: West Indian Religious Sect Development in Britain". Journal for Scientific Studies of Religion Vol. 10 (1971):pp 115-123.

- Kiev , Ari. "Psychotherapeutic Aspect of Pentecostal Sect Among West Indian Immigrants to Britain". The British Journal of Sociology Vol. 15 (1964):pp 129-138.

- Mitchell, Mozella. Crucial Issues in Caribbean Religions. . New York: Peter Lang Publishing Inc, 2006.

- Schmidt, Bettina E. “The Creation of Afro-Caribbean Religions and their Incorporation of Christian Elements.”

- Sankeralli, Burton, ed. At the Crossroads African Caribbean religion and Christianity. St. James: Caribbean Conference of Churches, 1995.