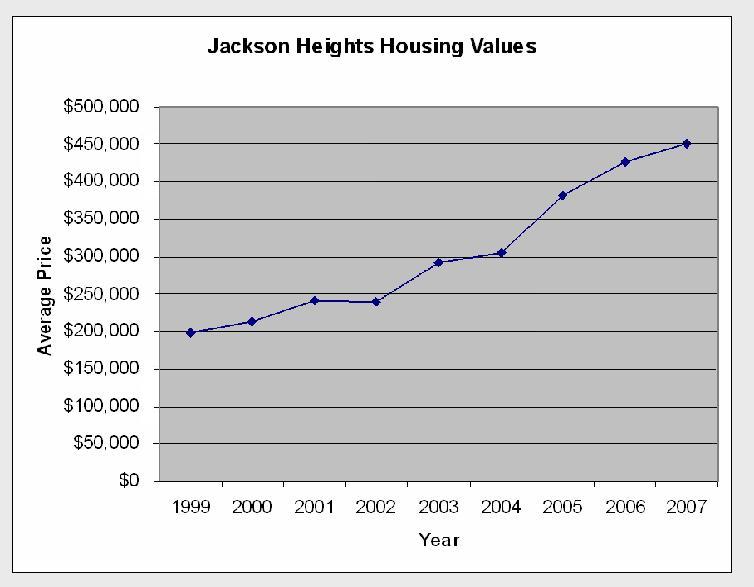

GentrificationFrom The Peopling of New York CityStarting in 1909, Edward MacDougal and his Queensboro Corporation built Jackson Heights for white, upper middle class residents, and included privileges such as tennis courts, golf courts, playgrounds, and the like. The goal was to “create a city within a city,” and allow residents easy access to Manhattan, but to also provide a step back from the rapid, urban lifestyle. (Community Greens: Jackson Heights) Moreover, the Queensboro Corporation, and other early developers, placed restrictions that prevented other ethnic groups from residing in Jackson Heights. At first, Jews and Blacks were barred from purchasing private space -- ie, homes, apartments, etc. -- in Jackson Heights. While Jews were allowed to move into the neighborhood after the late 1940s, Blacks “continued to be excluded from the area until … 1968 [and possibly] through the 1980s” (Kasinitz, 163-4). This continuing struggle over space is largely embodied by the movement to establish a Historic District in Jackson Heights. In 1993, a majority of the "Garden Apartments" built by the Queensboro Corporation were denoted as being part of Jackson Height's Historic District, which prevented any glaring alterations to property in said area without city approval. This establishment of a historic district, to preserve the aesthetics of the neighborhood, has resulted in a substantial increase in property values, according to Real Estate agents, and has attracted numerous affluent residents. (Community Greens: Jackson Heights) The established Historic District includes more than 200 buildings and private homes, many of which were built by the Queensboro Corporation in the first half of the 1900s. The effort was campaigned by the Jackson Heights Beautification Group (JHBG), whose leaders and board of directors were mostly “middle-aged, white business owners and professionals.”1 As they owned the co-ops and private homes, among their priorities were the area’s reputation and appearance. Further, only upper-middle-class (and generally, ethnic white) owners could afford to preserve the buildings in their “historic pristine condition.” Most people of color - then and now - cannot afford to live in the historic district, making it an almost segregated, completely white area. This transformation will increase as the gentrification proceeds in the neighborhood, bringing the ethnic diversity down through the pricing out of less affluent, non-white residents. A few years prior to the official establishment of the Historic District in Jackson Heights, apartments in the neighborhood began to be advertised to a more exclusive clientele than during the earlier years of the development of the neighborhood. "Offering by prospectus only" was a phrase which accompanied many advertisements for co-ops, apartments, and houses in the area. In many ways, this signaled the advent of an advertising campaign to re-represent Jackson Heights as an area that was primed for middle-class redevelopment and gentrification. (GUYS: HOW DO I CITE A COUPLE DECADES WORTH OF NY TIMES MICROFILM? THANKS!) These processes can also be seen in the advertisement of European names given to co-ops in the historic district, the preservation of old Tudor buildings, and existence of a Greco-Roman statue in the internal garden of a co-op. At this point, gentrification is serving to increase the struggle over space in the neighborhood. As less affluent, often non-white residents (and potential residents) are being priced out of buying homes in Jackson Heights, spatial and perceptual divides in the neighborhood are increasingly being framed in terms of economics and class. This is not to say that gentrification naturally increases the awareness of class issues in a neighborhood, of course; but it is interesting, when walking around the neighborhood, to hear how some peoples' perspectives have become less focused on ethnicity and more focused on class. In an interview conducted with two women sitting in Espresso 77, an independently owned coffee shop, one mentioned that she felt an ethnic divide in Jackson Heights. She said the people of Jackson Heights do not get along. She stated that the conflict begins between people who are coming into Jackson Heights with more money and the older residents of Jackson Heights. Further, she said these people with more money stand out against the people who have lived in Jackson Heights for elongated period of time because they are very arrogant and like to show off their money, while the older residents are more humble. This woman's analysis of her neighborhood is very interesting because she spent much of her time speaking about 'old money' versus 'new money,' yet also made the assertion that this was an example of 'ethnic division.' This serves to demonstrate the pervasiveness of the emphasis on diversity that the representations of Jackson Heights entail; yet it also shows a somewhat classed interpretation of how the neighborhood is changing with gentrification. The second woman interviewed in Espresso 77 mentioned that she feels the most tension in the co-ops. The newcomers to Jackson Heights are willing to pay more money for the apartments, which in turn drives real estate prices up. She also mentioned that the conflict is more of a class conflict than an ethnic conflict. These women were clearly against the gentrification of Jackson Heights and the subsequent influx of upper middle-class residents, which was demonstrated both by their words and their choosing to purchase their coffee at an independently owned coffee shop rather than the Starbucks just around the corner. When asked about the ethnic divide in the area, one couple having brunch at that Starbucks replied, "divide for us is probably the wrong word." They claim not to feel any sort of divide in the neighborhood. This couple represents the “newcomers” that the women sitting in Espresso 77 were describing. These middle class residents (as the women assert) are the cause of gentrification in the neighborhood. They often go to different places to eat and they “enjoy the variety”. This demonstrates a success of real estates' advertising campaign of selling ethnic diversity to affluent newcomers. Moreover, residents of the neighborhood have also clashed with businesses, including Indian business owners and shoppers, a majority of whom are not residents of Jackson Heights. The success of local Indian businesses has caused the “[displacement] of long-established, familiar stores and restaurants in favor of more profitable ones” from both “outsiders” and “foreigners,” upon which older residents have looked negatively (Kasinitz et al., 169). Norman L. Horowitz, a real estate attorney who has worked all over Queens including Jackson Heights, stated that he believes that Jackson Heights is ready for big investment. He says, "I think stores are on the rise there, and nicer and more upscale businesses are coming into the area as far as I can see. The area is ready for an investment in a more upscale real estate purchases such as fancier condos and homes. The neighborhood is getting to that point where people can afford it and it would boost the neighborhood." These statements clearly supports the fact of growing gentrification in Jackson Heights. If you need proof of gentrification, look no farther than 74th Street. The community district is aware of 74th Street being a major commercial area in the neighborhood. Therefore the community district has regulated this part of the neighborhood. In which improving sanitation pick up, enforcing traffic regulations, increasing police/traffic enforcement in the area of 72nd to 75th Streets, 37th Road to 35th avenues in order to better move traffic and to reduce noise and air pollution and modifying the parking regulations as well. Statistically, too, the gentrification of Jackson Heights can be seen in the rising housing costs over the past decade. Over the past ten years, the average home price in Jackson Heights has steadily increased, except for a slight decrease in prices from 2001 to 2002, when the U.S. economy was in a recession. Today, the average cost of a home in the neighborhood is estimated at $451,100, whereas, in 1999, the average cost was $198,200 -- a more than double increase of 128% in just nine years.

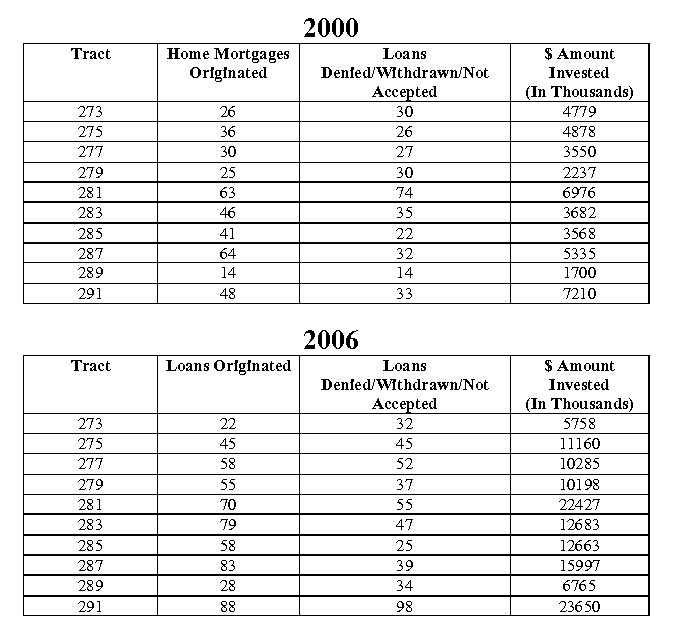

(Source: PropertyShark & U.S. Census Bureau)  (Source: Property Shark & U.S. Census Bureau) In correlation, mortgage investment data also paints a picture of gentrification. Between 2000 and 2006, the amount of money invested in Jackson Heights increased dramatically, more loan applications were filed, and more loans were originated (Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council). Here's a breakdown by census tract:

While the residents of Jackson Heights use the same space, they hardly ever come together for everyday activities. They lead separate lives, in which residents stay in what they perceive to be their boundaries. This creates dominating sections in Jackson Heights, such as the Latino region of Roosevelt Avenue and the heavily dense Indian commercial center of 74th Street. All these factors further contribute to the idea that Jackson Heights is a conglomerate of divided sections that form a whole, but each regions separate and isolated. (NOT ALL OF THIS SHOULD BE ON THIS PAGE I DON'T THINK) In an interview with Norman L. Horowitz, a real estate attorney who has worked all over Queens including Jackson Heights, I gathered information that both supports our claim of growing gentrification in Jackson Heights and also disproves it a little. On the one hand, he explained to me how he has assisted on house sales with white, middle-class Jews. He has never seen a purchase in that group, which is significant. This white, middle-class group is moving out while large groups of immigrants are still moving in. In fact, according to Mr. Horowitz, the three largest practices specializing in bank-closings in Jackson Heights are primarily staffed with Latinos, Pakistanis, and Asians, to accommodate the large influx of those specific buyers. This is not supportive of growing gentrification because we are seeing the middle-class leave and new immigrants come in.

Human Resource Administration - Elderly population increases - What is the ethnicity of the elderly?

2001 – 28, 624 2004 – 54, 147

2000 – $15,193 2001 – $18,256 2004 – $44,801 Education • schools are overcrowded • 9 elementary schools (PS 69, 92, 127,143,148,149,212,222, 228) • 2 intermediate schools (i.s 145, 230) • No high school Even with 9 elementary schools, they are still overcrowded???? Why are there no high schools in community district three??? |