Early History of Greenwich: 18th-19th Centuries

From The Peopling of NYC

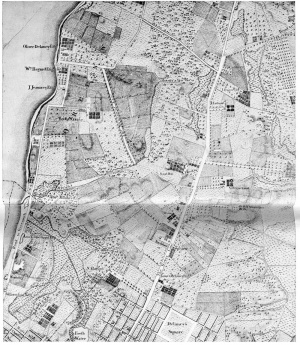

Greenwich Village was once a marshland called Sapokanikan by the Native Americans who fished in the meandering trout stream known as Minetta Brook. Minetta Brook flowed from 23rd Street to Union Square and then down into the Hudson River and still runs beneath those streets. It once went under Minetta Street, until NYU diverted its path. This area would form a village called Noortwyck (North District), before a settler from the Long Island village of Greenwyck (Pine District) would relocate there and give his new property that name. Others attribute the location's name to the second governor of New York, General van Twiller, who bought a tobacco plantation in the area, and, called it "Greenwich." The name "Greenwich Village" first appears on a map in 1713.

Contents |

Escape from Epidemic

Disease has shaped much of the Village's early history. For more than a century, yellow fever plagued New York (as might have been expected of a town wherein droves of swine fed upon garbage in the streets). City inhabitants acquired a habit of traveling to Greenwich Village and other places that were also then considered rural, distant, and safe from contagion, though they are now long since involved in the city proper (Haswell).

In 1798, when a cholera epidemic wracked the city of Manhattan, a burial ground for the victims of the disease was established in what is now Washington Square Park. Over the next three decades, it was a potter’s field where the poor were buried. It was also the burial place for those hanged on the infamous “hanging tree.” (Beard)

Bank Street in the Village was named for the Bank of New York. A clerk in the Bank of New York’s Wall Street headquarters was stricken with yellow fever in 1798, and to avoid being quarantined and closed in the future, the bank bought eight lots on a nameless Greenwich Village lane and erected a emergency branch. Bank Street boomed when an 1822 epidemic drove hundreds of city residents and businesses to the village.

During the 1822 epidemic, many chose to settle in Greenwich Village permanently, increasing the population fourfold between 1825 and 1840 and spurring the development of markets and businesses. Shrewd speculators subdivided farms, leveled hills, rerouted Minetta Brook, and undertook landfill projects. Blocks of neat row houses built in the prevailing Federal style soon accommodated middle-class merchants and tradesmen. A fashionable area developed around Washington Square Park, at the foot of Fifth Avenue. By 1825, the editor of the New York Commercial Advertiser stated that “Greenwich Village is no longer a country village. Such has been the growth of our city that the building of one more block will connect the [Lower East Side and Greenwich Village].” (Beard). The potter’s field was closed in 1826 and transformed successively into a military parade grounds and a spacious pedestrian commons. On the perimeter of Washington Square, stately red brick townhouses, built in the Greek Revival style, drew wealthy members of society. The crowning addition to this urban plaza was the triumphal marble arch designed by Stanford White (Greenwich Village Society for Historical Preservation).

The rich move in...

Greenwich Village was essentially a suburb of the main Manhattan settlements to the south. Evidence of the wealthy people who lived there survive in traces of luxury like the houses on Colonade Row and Washington Square North. Greenwich Village was a posh place to live until the 1840s, when the rich began their march up Fifth Avenue.

The 1820s and 30s saw a rise in residential construction in the neighborhood. Businesses had begun to overrun residential streets and the middle and upper-class fled north to the relatively sparsely settled Greenwich Village area. The Charlton-King-Van Dam District was the center of middle-class housing, or what James Fenimore Cooper called “second-rate genteel house[s].” The upper class clustered on LeRoy Place between Mercer and Greene Streets and on the north side of Washington Square Park. Thomas Bender notes the significance of this development was that it created an exclusive residential housing market for the middle and upper classes and the “commuter,” someone who could afford to travel to work, a luxury that immigrants did not have, was born. Its socioeconomic implications essentially created a new spatial order in the city as well as a new social order (Beard).

...And out

By the 1850s, tenement housing began to emerge on the south side of Washington Square Park, especially near Bleecker Street. These tenements replaced the aforementioned second-rate genteel houses east of the Bowery. Class divisions become apparent in the divergent architectural styles of the Village. Hundreds of brownstones, the bourgeois residence of choice, were built post-1850 just north of the Square, and signified the northern movement of the middle class. Brick Federal style and Greek Revival structures were the choice architectural styles of merchants and artisans. Residential growth leveled off in the Village and in general below 14th Street, expect in the Lower East Side, as the population surged ever northward. In 1846, only twenty of the two hundred richest men lived above 14th Street. By 1851, only five years later, one hundred of the two hundred richest men lived above 14th Street (Beard).

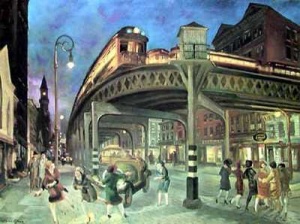

The building of the elevated railroads in 1869 aided the middle class march up Fifth Avenue. The poor were left behind in the tenements. By 1876, fifty percent of the city’s population lived in tenements. Post-1870, city buildings rose to ten stores. Similar structures were largely absent from the Village, which remained isolated from the rest of the city. Fifth Avenue did not extend south of Bleecker Street until the 1920s; Sixth and Seventh Avenue until the 1930s. Also, the strange street pattern precluded the more orderly city life that developed in the parts of the city that had been laid out on the grid of New York City. Having been established prior to the 1811 Commissioner’s Plan, Greenwich Village retained its quirky street twists and turns (Beard).

By the turn of the twentieth century, the “American Ward,” a quarter around Washington Square Park, received a huge immigrant population influx into what had been a historically black neighborhood (Beard).

Why It's Still a Village

Greenwich Village's irregular street grid formed when people, rushing for land, laid out plots with little concern for overall community structure. It survived the 1811 Commissioner's Plan. The turned and twisted streets surrounded by the straight grid gave the Village a feeling of being secluded from the City that it still retains today. This feeling attracted the rich and middle-class and, after they moved out, journalists, writers, artists, poets, musicians, revolutionaries, and tourists.

Sources:

Beard, Rick, and Leslie Berlowitz, eds. Greenwich Village: Culture and Counterculture. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press for the Museum of the City of New York, 1993.

The Greenwich Village Society For Historic Preservation: Village History. 2002. 17 Apr. 2007 <http://www.gvshp.org/history.htm>.

Haswell, Charles H. Reminiscences of New York By an Octogenarian (1816 - 1860). 1896. 17 Apr. 2007 <http://jmisc.net/octo/octo-06.htm>.

Moscow, Henry. The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. Hagstrom Company, 1979.

Shorto, Russel. The Island at the Center of the World. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.