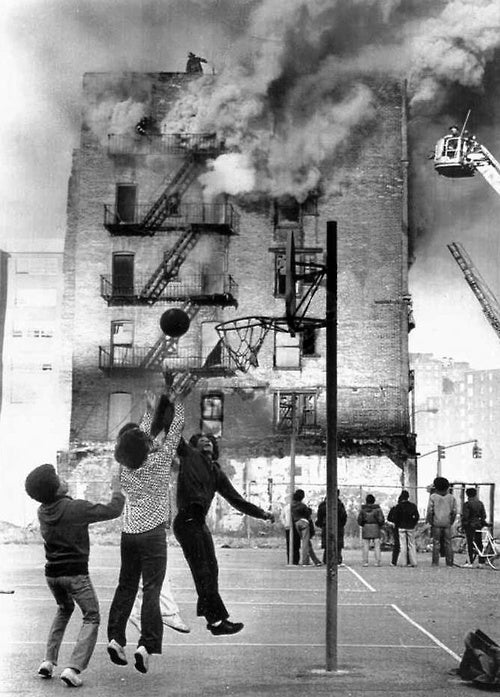

So far in the class, many of our readings, especially our latest one from A Plague on Houses, have highlighted a common misconception that improvement and development can only happen with the destruction and removal of struggling, under-resourced neighborhoods. Perhaps, as was the case with Robert Moses, this destruction had good intent; by razing homes and buildings in dilapidated and disadvantaged communities, room could be made for new infrastructure for industry and urban renewal. In other words, it was this idea of starting from scratch – completely eradicating all the bad and replacing it with new, idealistic development projects that would wholly transform a community for the better.

Undoubtedly, there are numerous flaws to this notion. One of the most obvious flaws, as we’ve discussed previously in class and as we see described again in this reading, is the question: where do the displaced people go? It’s a question that persists today, as rezoning and redevelopment projects continue to force poor, nonwhite communities out of their homes to make way for industry and new housing initiatives.

Underneath this problem of displacement and relocation also lies a persisting racist point of view. Daniel Patrick Moynihan and the Rand Institute exemplify this perspective. Improperly interpreting and analyzing statistical data, and disregarding numerous other variables that affect the incidence of fires, they targeted poor, nonwhite communities as scapegoats for a larger, much broader problem of unsuccessful and ineffective urban planning and policy-making. They characterized such neighborhoods as sick and irreparable and used their statistical misinterpretations as the faulty justification behind limiting resources and facilities that were originally meant to serve and protect the people. Ideals such as “benign neglect” and “planned shrinkage” were thus euphemisms for discrimination and neglecting the government’s most fundamental role of keeping all citizens, regardless of race or income, safe.

It is thus extremely ironic, yet unsurprising, that Moynihan’s and Rand’s cuts in the public service and fire safety sectors actually led to an increase in the incidence of fires and neighborhood deterioration. A lot of this, in large part, was due to their drastic oversimplification that poor neighborhoods were the cause, rather than the effect, of urban decay. Additionally, their extremely poor use of statistical data and mathematical models only proved to exacerbate the problems Moynihan and Rand had originally sought to fix. Hence, by wrongfully interpreting data to accommodate for underlying racial and economic discrimination, Moynihan and Rand not only failed to decrease the incidence of fires and improve neighborhood conditions, but also created even more problems that negatively impacted poor and wealthy communities alike.

Discussion: How can we prevent policy-makers from targeting poor, minority communities for displacement and relocation? In other words, how can we limit the racial and economic discrimination that appears to persist in urban planning today?