Video editing and Prezi done by Brian Rivera

Written Blog done by Sarah Hussain

Throughout the semester, we attended several events; each event provided us with an “Aha moment,” or a moment where we came to some sort of conclusion or understanding about art. A collective “Aha moment” we had was at Fall For Dance at New York City Center. We both felt this was a thought-provoking performance for both a dance expert and novice. A dance novice, such as Brian, was thoroughly entertained by the variety of dances being performed as it encompassed tap, hip hop/contemporary, ballet, and modern. The simplicity of the entire performance and the absence of dramatic lighting and backdrops allowed the audience to solely focus on movement. This performance enlightened newcomers as to how dance appeals to emotions. Not only can tap dance create its own music, but dance can also be used to tell stories. Someone familiar with dance was able to critically analyze the choreographic elements of each dance and note the differences and similarities. I was able to form an opinion about choreography after watching this performance. I decided that dance movement is an art form in itself, and no additional music and lyrics are necessary to drive the dance. In fact, I believe sometimes the music can overshadow the music as it did in “Mo(or)town/Redux” choreographed by Doug Elkins. This piece had brilliant choreographic elements included such as tempo change, level change, partner work, breakdancing, and stillness. Yet, I believe the well-known ‘60s music and storyline of Shakespeare’s Othello overshadowed the dancing for audience members that did not understand the technicality, difficulty, and athleticism of what was being performed. It was too dramatic in both of our opinions.

We preferred The Royal Ballet performance entitled “Fratres” and choreographed by Liam Scarlett. Brian admired how the duet partners melted into one another and appreciated seeing the fluidity of ballet live. I admired that there were no lyrics, gimmicks, or props driving the choreography. It was thought provoking to see Scarlett, as a choreographer, create both feelings of unison and disjoinment within the movement. We both agreed that the emotions coming from the performers seemed real and genuine. The movement was powerful enough to speak for itself. We realized no theatrical elements are always needed in dance performances if the performers have enough passion and energy. After comparing the two pieces, we came to the conclusion reasons why we preferred “FRATRES” over “Mo(or)town/Redux.” It was because we liked the fact that there was no set storyline for the ballet. We believe dances should be ambiguous and left up to interpretation for the audience. That is what essentially makes dance an art. Mere movement can evoke emotions within people and allow viewers to connect with it in any way they choose. After attending this performance, we decided that when art is vague, it is more powerful.

Our other overall “Aha moment” was at “You Never Can Tell” at the Pearl Theatre. After seeing this play, I had a new appreciation for theatre since I was avidly looking for scene changes, smooth transitions, backdrops, and character interaction. As an avid theatregoer and performer himself, Brian came to realization about how necessary character development is and how difficult it is to have mannerisms of the characters unfold. In both “You Never Can Tell” and “Twelfth Night,” we came to conclusions about written plays and performed plays have a completely different deliverance. After reading “You Never Can Tell” and watching it, different emotions were evoked from us. When watching the play, characters delivered lines quickly, driving the plot, and keeping the audience entertained from beginning to end. When reading “Twelfth Night,” the Shakespearean literature was at times difficult to understand. When watching “Twelfth Night,” jokes were delivered in a very straightforward manner and there was much comic relief. After reading and attending both plays, we came to the conclusion that they are both obviously forms of art, but it is easier to interpret themes when we have a visual.

The Brooklyn Museum was a great introduction to the seminar because it forced students to collaborate, analyze, and interpret painting and portraits. We agreed that the different European sculptures and even household and common daily items presented in the museum were thought-provoking and helped set the tone for the entire seminar. Going to this event and collaborating ideas with others helped us form opinions about are and decide how/if it affected us and how/if we could connect with the piece. To us, the discussion of art should be valued.

Visiting the Louis Armstrong House, which was right in Corona, Queens gave insight into the personal life of Armstrong . We came to the conclusion that whether consciously or subconsciously, learning about an artists influence how we view his/her work. The area surrounding Chelsea also influenced the way we viewed the galleries. It was exciting to be immersed within the Chelsea environment with all of the graffiti, purposely placed street art, and High Line.

After attending the opera, “Rigoletto,” we both had a new outlook on opera. It was not a boring, dry, upscale event that we had once perceived it as. The third act was incredible and kept us entirely entertained despite it being in Italian. Not only was the singing incredible, but also the acting and scenery were captivating. We now have a new appreciation for opera as an art.

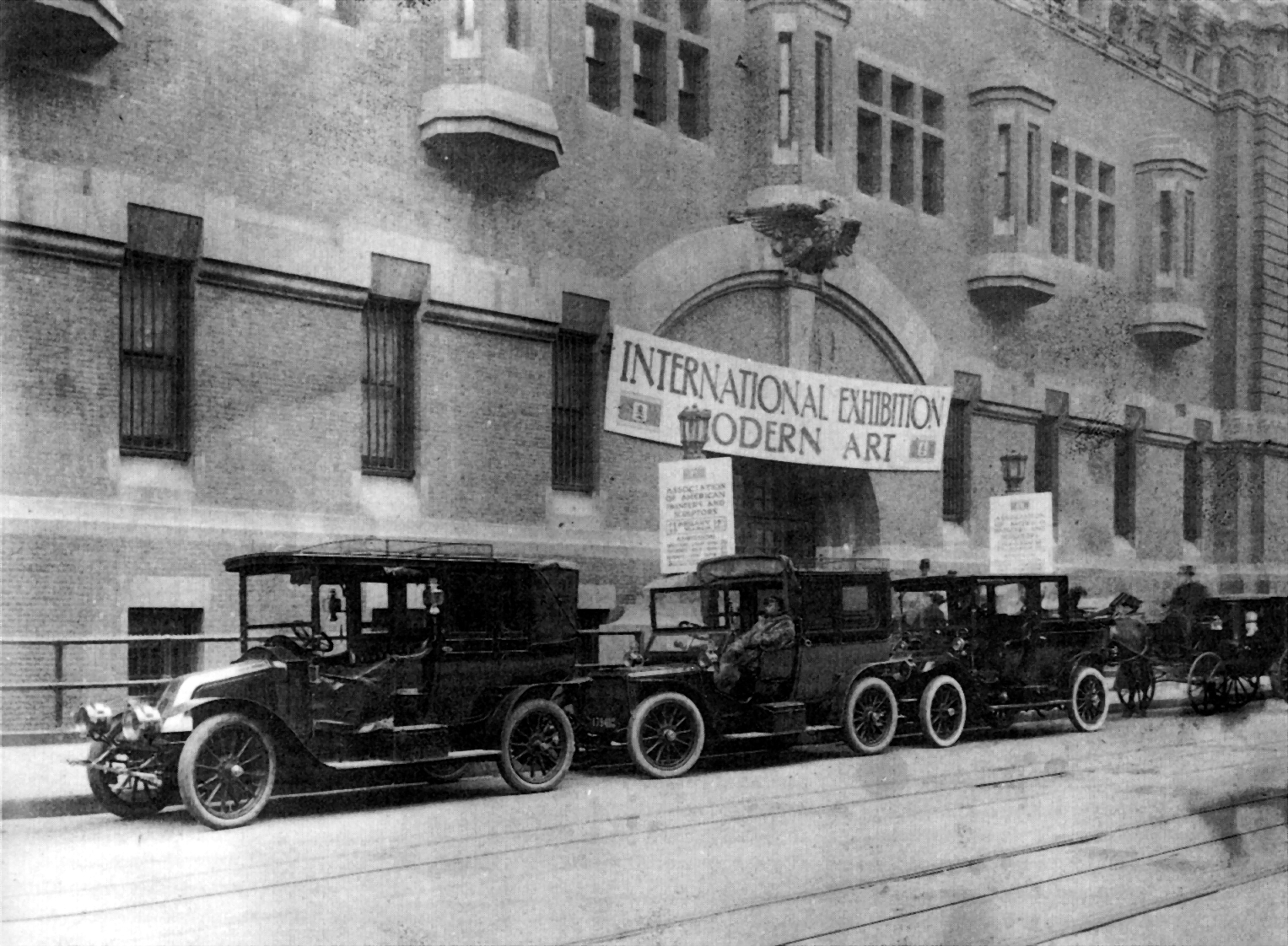

These two factions represented the competing visions of modern art and its future in America, which came from late nineteenth century ideas about subject matter, focusing on urban life and pressing social problems. The new European works brought a new sense of modern being about art itself, questioning standards through experimental use of form and color.

These two factions represented the competing visions of modern art and its future in America, which came from late nineteenth century ideas about subject matter, focusing on urban life and pressing social problems. The new European works brought a new sense of modern being about art itself, questioning standards through experimental use of form and color.