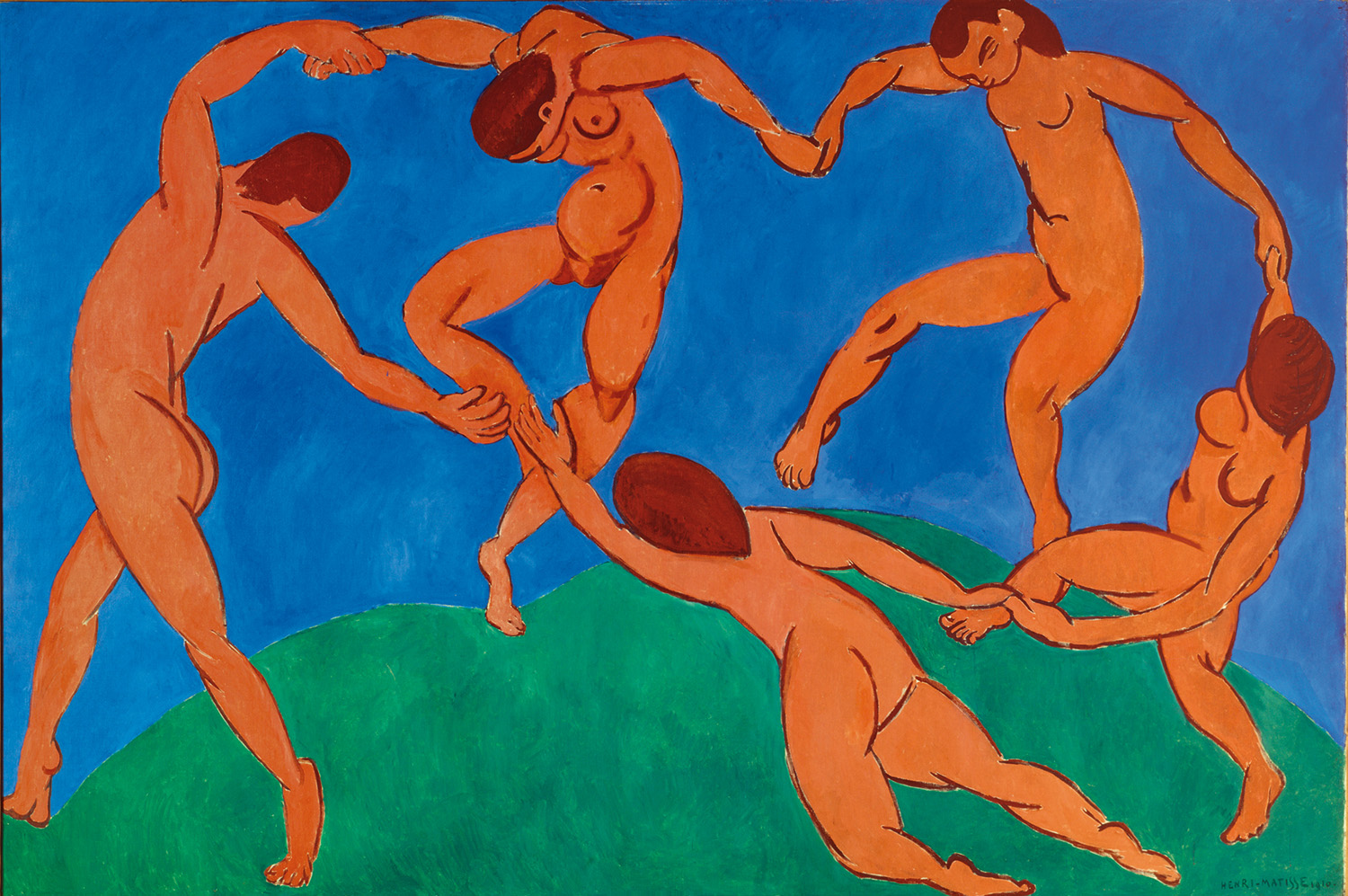

‘Dance’, Henri Matisse, 1910.

‘Christina’s World’, Robert Wyeth, 1948.

Although the early twentieth century saw the maturation of a number of abstract art movements, not all painting from that time period was in the style of a Picasso or a Kandinsky. In order to make that distinction while still observing the purely twentieth-century sensibility that imbued all works from that time, I have decided to contrast Matisse’s Dance (1910) and Robert Wyeth’s Christina’s World (1948).

To compare these works formally is no arduous task. Their differences are fundamental and pretty obvious. Whereas Wyeth paints Christina and her world in the muted browns, blues and yellows one would find in any conventional prairie scene, Matisse’s colors resemble reality only crudely. The bright blue of the sky, the bright green of the grass and the striking orange-brown of the figures are the sorts of colors a child would use; in fact, the painting could almost have been accomplished in crayon. But that is almost certainly what Matisse was going for. Wyeth establishes a clear setting with a realistic figure that looks like something which could actually happen. Matisse’s scene is that of a group of five nude figures dancing in a circle reduced to its essential elements. He divorces the scene from any realistic setting and places it in a kind of generic void-world. Whereas the textures and shadings of Wyeth’s painting seem to make sense, Matisse is almost entirely unconcerned with the problems of light and perspective.

But although these works are so radically different in form, in sensibility they are quite similar. Both Matisse and Wyeth are painting a serene, bucolic environment – albeit in their own different ways – but with a twist. Something is up, something is going on. Matisse’s dancers and Wyeth’s Christina are all in a dream world. The dancers contort themselves in impossible ways and their figures are grotesque, as if they are members of some forgotten hominid group, or overgrown fetuses. And although Wyeth’s portrayal of Christina is perfectly realistic as far as her anatomy is concerned, brilliantly he decides not to show her face. She is looking at the same thing we are looking, that house with its fence and that barn – her world. So we know what she’s looking at, but we don’t know how she sees it. Because of this there is great tension in the painting, and its ambiguity is beautiful. In their own idiosyncratic ways, both paintings create a tension, a difficult-to-place feeling that something is strange in our world, that our world is not so different from the settings we occupy in our dreams, no matter how hard we try to convince ourselves otherwise…