The oil market is undergoing a paradigm shift. Oil hit an historical low of $35 a barrel on the Brent Crude benchmark, the international measure of oil prices. Oil has consistently hit record lows for the past several weeks and does not promise to go up anytime soon. This is great for consumers: spending less at the pump means more discretionary money for consumption. Theoretically, this is good for a consumer driven economy like the United States, but more Americans appear to squirreling their money in savings. This is understandable given the 2008 recession. Unfortunately, it gives even less space from which the economy can grow. Growth must therefore rely on other fields. Some of it comes from the so-called “onshoring” of manufacturing jobs, the process by which certain high-tech manufacturing is positioned in the U.S. for various reasons. Much of it comes from the exploding tech industry and all the related service fields it encompasses. The most striking bit of growth, though, lies in the oil field.

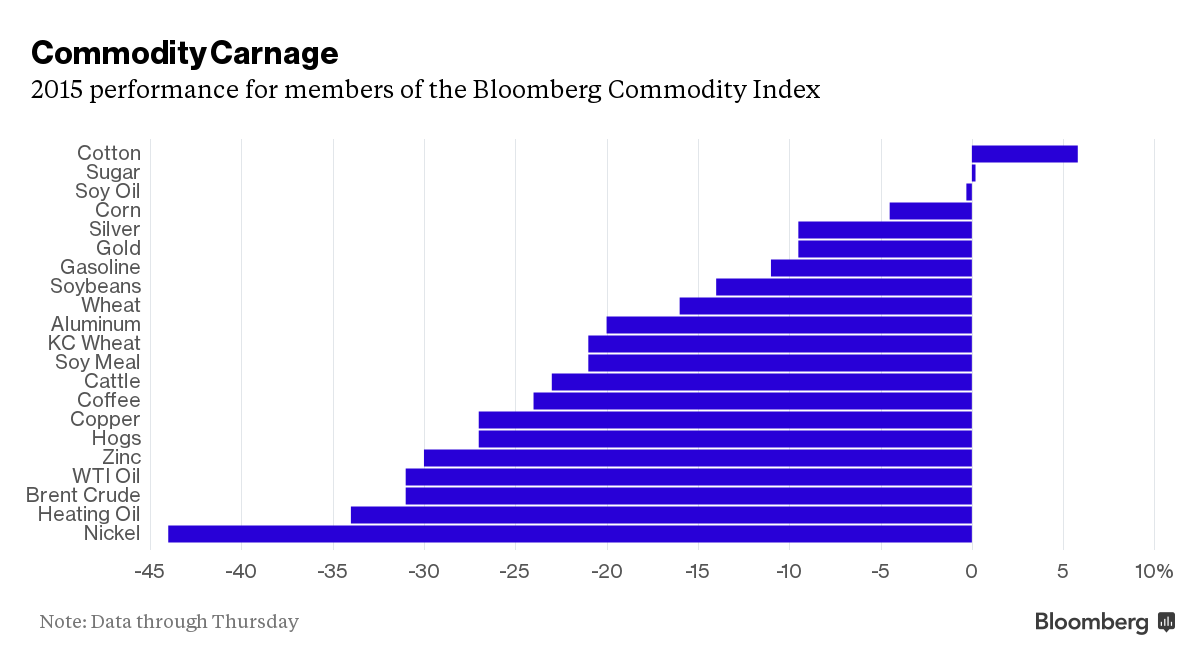

Oil prices haven’t been this low in a while

Hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” is a new development. Essentially, it is a way of extracting oil resources from deep underground that were previously inaccessible because of a lack of advanced technology. Breakthroughs in drilling methods have granted access to these resources. The United States is well poised to extract them. Our unique land rights ensure the ease with which companies can extract oil from land they own. Our economy is dynamic enough to ensure the success of companies that smartly take advantage of the oil market, while the ones that don’t fail. Our access to technology and associated resources needed for fracturing, such as huge amounts of water, are unparalleled compared to many other countries. These factors combined to produce a renaissance in American oil production. Around the beginning of the decade, for the first time in several decades, the United States began exporting oil rather than solely consuming it.

Around the same time, Saudi Arabia increased its own oil production. This was done to secure the global market against the drop in consumption of Iranian oil due to economic sanctions. Sanctions from the European Union, the United Nations, and the United States curtailed Iranian market share. The former General David H. Petraeus, under orders from the Obama administration, persuaded the al-Saud regime to ramp up production to compensate. Saudi Arabia was only too happy to snub its regional rival and supply the world with its own oil, filling its coffers in the process. Within a few years, though, the geopolitics evolved: the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was passed among Iran, the U.S., England, France, Russia, China, and Germany. This nuclear deal offered Iran broad sanctions relief for concessions regarding its nuclear weapons development program. Centrifuges were disarmed, weapons facilities transformed into research stations, and an inspections regime by international watchdogs was enforced. In exchange, Iran can once again sell oil to Western markets and a flood of foreign businesses are slated to expand into Iran. This process is ongoing, but Iran is fully poised to reintegrate into the global economy, for all the good and bad that entails.

Iran’s entrance into the world economy means tighter competition for Saudi Arabia, which is one of the largest producers of oil. Saudi Arabia is also a monarch run by the al-Saud royal family. The oil industry finances almost 80% of its national expenses, including its extensive welfare programs, and provides for almost half of its GDP. Such reliance on a single industry makes Saudi Arabia vulnerable to market volatility. One example was during the 1990s, when several factors, including an economic crisis in East Asia, lowered oil prices drastically.

On the flip side, Saudi Arabia benefits greatly when oil prices are high. The most well known example is the oil shock of 1973-74, during which OPEC enacted an embargo over geopolitical reasons regarding American support of Israel. Another example was during the Iran-Iraq War, when Saudi Arabia provided reassurance over an otherwise uncertain oil market. In all of these instances, Saudi Arabia was the decisive oil producer. The kingdom always pursues a strategy that ensures maximum market share, taking on defensive or offensive positions as the situation demands. This time is different: Saudi Arabia faces a much more competitive oil market.

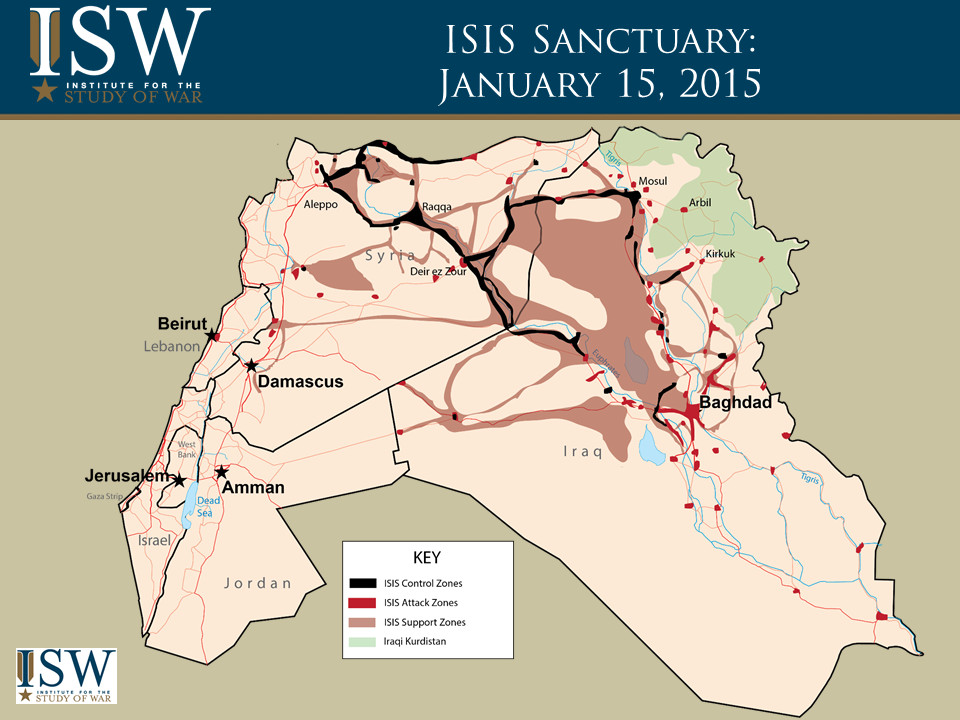

In keeping with its goal of retaining maximum market share, Saudi Arabia has refused to lower production. It is still operating at the inflated high from when it increased production under request of the Obama administration. Its logic is to drive oil prices so low with surplus supply that American manufacturers will be forced out of business. It is a war of attrition, in which Saudi Arabia hopes to bleed out its competitors faster than it bleeds itself, like how chemotherapy aims to rid the body of cancer before destroying the actual body. It has also convinced other OPEC members to maintain levels of production. Saudi Arabia, however, has the lowest break-even price per barrel of oil, which makes it the best suited to pursue this aggressive strategy. On the other hand, it is the most reliant on oil revenue. An unhealthily high proportion of its citizens are government employees, paid for by oil revenue. Its most valuable firm and largest employer is Saudi ARAMCO, the nationalized oil company. The Economist estimates its worth at trillions of dollars, possibly making it the most valuable company in the world, but much of that value lies in untapped oil reserves that are decreasing in worth. Without substantial increases in oil prices in the foreseeable future, Saudi Arabia will have trouble paying its employees, let alone balancing its budgets. Social security payments will undoubtedly fall while taxes may have to be imposed. The unemployment rate may rise, which is troublesome for a country as young as Saudi Arabia: almost half the population is under 25. Young, unemployed men are especially problematic, as they are often prone to violence and lack of productiveness. Factor in potential religious extremism inspired by ISIS, which itself gains its theological inspiration from Saudi Arabia, and the danger becomes much more severe.

Saudi Arabia’s plan is to bleed American oil producers out, but the American economy is nothing if not dynamic. Several smaller oil producers have in fact gone under, but others have merged together to make stronger companies. Over $300 billion in mergers and acquisitions (M&As) was either announced or proposed for the oil and gas industry, which helped make 2015 a record year for M&As. Such moves are necessary to maintain the competitiveness of the American oil industry in the face of OPEC’s strategy.

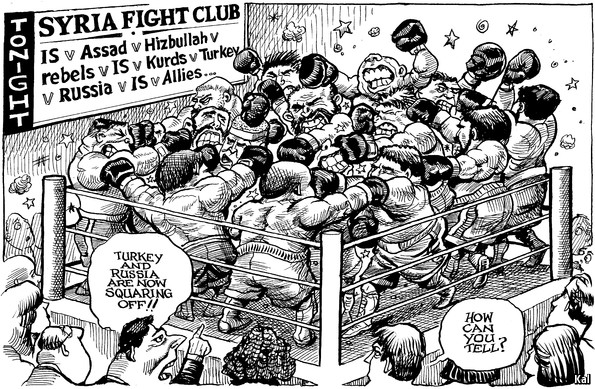

Russia is another major oil producer. President Vladimir Putin uses revenue from his country’s energy sector to fund ventures abroad. Geo-politically, President Putin’s interests vary considerably from those of the United States. Sometimes they align, such as the passage of the Iranian nuclear deal. On Syria, their alignment is at best circumstantial. On others, such as conflict in eastern Ukraine, the two are diametrically opposed. The state of the oil market is another such issue.

The Russian cost of production of oil far exceeds its current selling price. Russia, much like Saudi Arabia, is dangerously reliant on oil revenue to fund many of its domestic and foreign activities. The current slump in prices is problematic. To make up the difference, a debate is raging in Russia now on cost saving measures, including cutting pensions for workers, raising taxes, and even cutting back on military costs. The government is also considering taxing oil companies on the funds that would normally be saved to explore new oil fields. Russia has a higher break-even price than Saudi Arabia, which bodes ill for President Putin. Additionally, Russia’s economy is closer to an oligarchy, where power, wealth, and entire industries are controlled by a few individuals, far more so than the United States’ economy. This ensures inflexibility, a liability that is sure to hurt President Putin’s domestic and foreign aspirations.

Congress also finally uplifted its oil export ban, allowing American oil to be exported without restrictions. Prior to the lifting, American exports were limited to oil refined in domestic facilities. This ban was legislated after the oil shock of 1973-74 to ensure a domestic supply if OPEC ever decided to engage in an embargo again. Of course, that never happened again and the export ban simply remained in place. While the ban prevented exports of unrefined oil, refined oil was allowed to be sold. Unfortunately, most of the oil American producers have been recovering through hydraulic fracturing is light crude, while most American refineries are suited specifically for heavy crude. While the US still exported oil which led to the current oversupply, there was an even greater amount that remained inside the country. Now that the ban is lifted, that oil will flow out to foreign markets that are suited to refine light crude. It will also make the Brent Crude benchmark of oil prices closer in range to the American benchmark, the West Texas Intermediate. This should make international trade among the US and other countries more seamless, but it will add to the current surplus.

Another oil manufacturer to enter the market is Iran. With the passage of the nuclear deal, the Islamic Republic will resume exporting its oil reserves to the international market. The agreement also unfreezes Iranian assets held abroad, estimated to be worth at least $100 billion. Much of that money may wind up in terrorist organizations, such as Hezbollah, to secure Iranian state interests, but that is merely a logical conclusion of realism. As Iran gains access to the international economy, its local economy will greatly benefit, but it remains to be seen whether most of that benefit will come specifically from the oil sector. Several of its other sectors, from retail to education to nuclear research, are developed enough to grant Iran a strong foundation and promise to grow even stronger. Iran’s increased role in energy can only put a downward pressure on the price of oil, which is terrible for producers like Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Venezuela. Iran, however, is not nearly as reliant on oil as many other producers and its economy is diversified and mature enough to handle a blow to its energy sector. Likewise, the US is diversified enough to not be dealt a critical blow.

While the world economy is experiencing a glut of oil, slow growth continues to persist. The Chinese economy has slowed down significantly, owing to worries over exports growth, currency valuation, and stagnation in manufacturing and financial services. Once a reliably growing consumer of oil, China is no longer the boundless market for oil it once was.

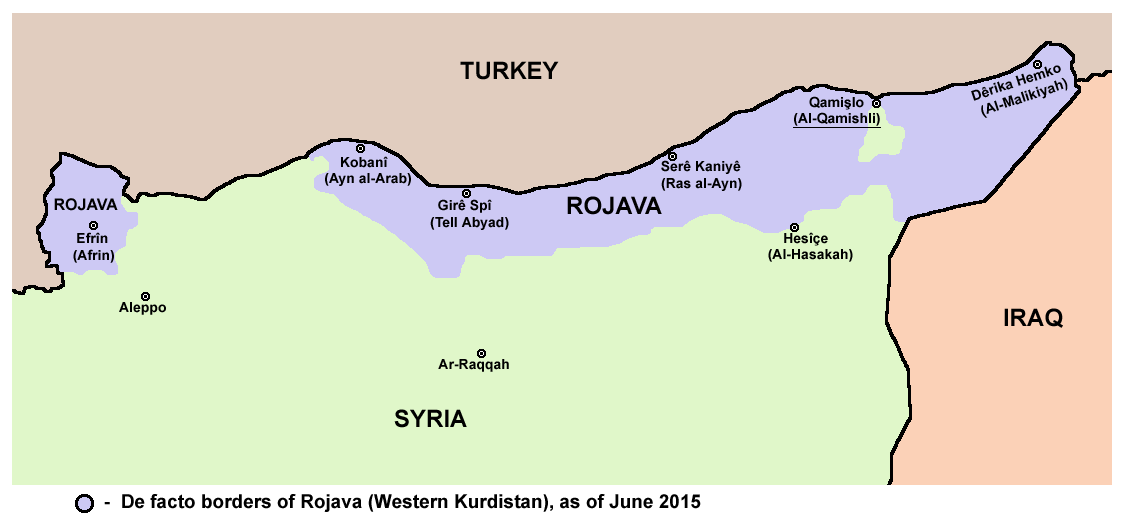

Economic turmoil in the European Union also hampers growth of demand. The EU is currently experiencing a bedlam of problems that threaten its very foundation. Its shattering problems with migrants, financially and socially unstable southern European countries, and a potential exit of Great Britain (the so-called, dreaded “Brexit”) pose massive problems. Terrorist attacks in Paris and Brussels, the latter of which is the de-facto capital of the European Union, have unnerved many Europeans against further immigration. Countries all over the continent are now instituting border controls to stem the flow of refugees from Iraq, Syria, and Northern Africa. We are witnessing the deterioration of the Schengen Convention, a treaty that makes possible seamless travel among EU countries. Hassle free European travel is one of the European Union’s hallmarks. This is changing as more countries enact border patrols, erect fences, and close borders. Consequently, the terrorist attacks have emboldened far right-wing parties, many of which advocate nationalism and xenophobia.

Prime Minister Angela Markel of Germany has led the effort to accept refugees. She is by far one of the strongest and most popular leaders in the EU, but she has expended much political capital trying to handle both the migration and financial debt crises of Europe. Her governing coalition recently suffered losses in local elections. She is holding for now, but it is unclear how long she can maintain herself and her party if she continues her position on immigration.

The EU faces a variety of crises, some of its own making and others as a result of turmoil in the Middle East. One of the primary reasons for the founding of the EU was to create a unified economic zone that allowed free movement of goods and people. In terms of the oil industry, these dilemmas will continue to hurt oil consumption in the short term. At worst, they threaten to bring the two decades long project of the European Union to come crashing down.

Meanwhile, American growth remains meager. As President Obama loves to mention, the unemployment rate is down to nearly pre-recession levels, but it is also true that this recovery is among the worst on record following any prior recession. Wages remain stagnant for the majority of Americans and median household incomes have barely budged in almost two decades. None of this indicates a potential surge in oil consumption anytime soon.

All these factors leave us with an oil supply at an all time high: the world now faces an oil glut. The paradigm of weakening demand and increasing supply is a double-edged blade. What is strange is the near simultaneous timing of everything that led us to this point. It’s so perfect that it almost sounds like a conspiracy theory.

It remains to be seen where all this will lead, but oil prices will likely not go up anytime soon. More American oil and natural gas companies may go out of business due to the deflationary pressure on prices. This will translate into lost jobs and the overall decline of the oil sector. But perhaps this is where we need to go: if the world is to make its inevitable shift to renewable energy, then perhaps a sustained crash in oil prices is the impetus it needs to make that shift.

Recent Comments