From The Peopling of New York City

Contents |

Overview

Because of the large number of German immigrants to migrate to New York, it's impossible for them to not leave an imprint on the city’s culture. Within the records of New York City history, names of German descent can be seen frequently. Some famous persons of German origin include condiments magnate H. J. Heinz, former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and paper manufacturer Frederick Weyerhaeuser. German Americans as a group introduced customs that are now considered part of the American way.

The Christmas Tree

The tradition of raising a Christmas tree dates back to the 1600s in Germany. Christmas itself was not elaborately celebrated in the United States until the Germans came over. Beginning in the late 1800s the German custom of raising the Tannenbaum, Christmas tree, and lauding Kris Kringle, Santa Claus, caught on in American homes. Thomas Nast, a German-born cartoonist, is responsible for sketching what is now the popular image of Santa Claus.

Free Speech

John Peter Zenger is remembered as the champion for the cause of free speech. Zenger was apprenticed to a printer named William Bradford as a child. In 1725, Bradford published New York’s first newspaper, the New York Gazette, in which Zenger eventually became partner of. When the partnership dissolved in 1733, Zenger established the colony’s first independent newspaper, the New-York Weekly Journal. In one of the first issues, Zenger called Bradford’s New York Gazette “a paper known to be under the direction of the government, in which the Printer of it is not suffered to insert anything but what his superiors approve of.” To make his point, Zenger’s paper published nothing that Governor William Cosby could approve of. After two months, Cosby finally took action. On August 4, 1735, he managed to bring Zenger to trial on charges of libel. Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, argued that public criticism of government officials was a safeguard of American liberties as long as it was true. His argument was so persuasive that the jury only took a few minutes to return a verdict of not guilty. The trial set a precedent that has given the United States a press that is the least restricted by government.

The Brooklyn Bridge

In 1854, Brooklyn, New York, was the fastest growing city in the country. The need for a bridge between Manhattan and Brooklyn was apparent and in 1869, John Augustus Roebling was hired to begin construction. However, he was injured while making some preliminary calculations and he died within three weeks. His son, Washington Roebling, finished the bridge using his father’s blueprints. The sad part of this story is that in 1872 Roebling Jr. contracted caisson disease, which was named after the watertight chamber that divers used to lay bridge foundations. It was common among workers because they were raised too quickly from great underwater depths. Roebling was forced to oversee the rest of the construction from the window of his Brooklyn apartment, while his wife, Emily, personally issued his directives on the construction site. To see the bridge finished was a gratifying sight to Roebling. At 1,595 feet in length, supported by two massive granite towers, four steel cables, and an enormous web of suspending wires, the Brooklyn Bridge was considered one of the most graceful spans ever built. On its opening day in 1883, more than one million people came to watch a group of luminaries, including President Chester A. Arthur, take the first walk across the East River. The Brooklyn Bridge was the first bridge to connect Manhattan to Brooklyn, and it has aided in the development of greater New York.

Carl Schurz

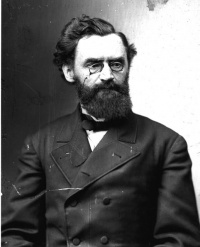

The career of Carl Schurz is considered by many as coming the closest to illuminating how a German upbringing matched so well to the needs of a growing America. Schurz was known widely for his strong antislavery views, as he was determinedly committed to securing justice for black Americans. He became renowned for his speech, “True Americanism,” in which he declared, “I think it can be said without exaggeration that there has never been in the history of this Republic a political movement [the abolition of slavery] in which the purely moral motive was so strong --- indeed, so dominant and decisive.”

Schurz joined the newly formed Republican Party around the same time as an Illinois representative named Abraham Lincoln. He campaigned vigorously for Lincoln in both the 1860 and 1864 presidential elections. He once wrote to his friend in Germany, “It is said that I made Lincoln president. This is certainly not true; but the fact that people say it indicates that I did contribute something toward raising the wind which bore Lincoln into the presidential chair and thus shook the slave-system to its very foundation.” Schurz continued to offer both advice and military service under Lincoln’s presidential terms, remaining in America as a brigadier general of volunteer Union troops. Besides Lincoln, Schurz advised almost every president from Lincoln to Theodore Roosevelt.

After leaving briefly due to his dissatisfaction with Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, to become a journalist, Schurz reentered into politics and in 1869 became the first German-born citizen to win election to the Senate. Later, he went on to be in President Rutherford B. Hayes’ cabinet as his secretary of the interior. He continued to champion his causes, including completely reorganizing the Bureau of Indian Affairs. He set up educational programs for young Indians and instituted a policy to conserve forests and lands.

Schurz’s contributions greatly changed the political and social atmospheres of the United States. When he passed away on May 14, 1906, in New York City, Mark Twain wrote a tribute to him. Twain compared Schurz to his childhood friend, Ben Thornburgh, and wrote, “I had this same confidence in Carl Schurz as a political channel-finder. I had the highest opinion of his inborn qualifications for the office: his blemishless honor, his unassailable patriotism, his high intelligence, his penetration; I also had the highest opinion of his acquired qualifications as a channel finder….I have not always sailed with him politically, but whenever I have doubted my own competency to choose the right course, I have…followed him through without doubt or hesitancy.”

General Contributions

German immigrants made many contributions as a whole and as individual persons. German-born citizens are largely credited with laying the foundations for scientific disciplines in the United States. American pediatricians recognize Abraham Jacobi as the father of their profession. Bernhard Eduard Fernow introduced the science of forestry and wilderness conservation in 1876. Anthropology became a scholarly discipline because of the 40-year career of Franz Boas, a German who emigrated in 1888. Boas’ students at Columbia University included Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead.

A large amount of contributions came from immigrants of the “Brain Gain.” When Hitler rose to power, 130,000 Germans came to the United States between 1933 and 1945. The people of this group of immigrants resembled earlier immigrants in many ways. They struggled with the language and unfamiliar surroundings of a strange land. However, World War II refugees did not come to the United States for economic reasons, therefore many of them belonged to the middle or upper class and was highly educated. Historians have often referred to this move by these men and women as a “cultural” and “intellectual” migration. It is referred to as a “brain gain” by the United States and a “brain drain” from Europe. The achievements of these refugees contributed to almost every discipline in America.

- Return to Cultural Contributions

- Return to Germans

References

Pages 95-109. Galicich, Anne. The German Americans. New York Chelsea House Publishers, 1996.