Second Wave

From The Peopling of New York City: Irish Communities

Migration: First Wave | Second Wave | Irish Hunger Memorial

|

Introducing the Second Wave

In the 19th century came the second wave of Irish immigrants to America. This mass immigration was due to numerous reasons, one being the horrific potato famine that swept across the country of Ireland. The English introduced the potato to Ireland in the 16th century in one variety. This particular type of potato proved to be susceptible to fungus, because later in 1845 an unknown fungus struck the Irish fields and killed the crops. During the time of the famine, 3 million people in Ireland depended on the potatoes for their daily existence, and every meal consisted of potatoes. There were numerous amounts of deaths, but there is no clear record of the exact number of deaths from the Potato Famine since members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) destroyed most church records in 1922. The estimates range from 500,000 to 1.5 million deaths due to starvation. Between 1845 and 1860 nearly 2 million people boarded vessels that took them to the American shores. From this photo, you can see that the amount of immigrants coming to America rose from a little more than 500,000 in the 1930s to more than 2.5 million by 1960. Thirty-nine percent of those immigrants were Irish. AAs America grew by the masses of immigrants flooding their ports, Ireland lost a communal culture, an ancient language (Gaelic) and its way of life altogether. Famine, death and immigration reduced Ireland’s population from 8.1 million in 1840 to 6.5 million ten years later in 1850. Aside from the death and devastation of the Great Famine; which caused millions of Irish natives to depart from their homeland, there was another reason for the mass immigration; assisted emigration from landowners.

Where They Moved

Old Living

The first wave of Irish immigrants settled mainly in New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland (a Catholic colony), East New Jersey, and South Carolina. In New York City, the Irish population was concentrated mostly in Lower Manhattan, in neighborhoods such as Greenwich Village, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen, and most prominently the multiethnic Lower East Side, specifically in the “Little Ireland” part. In the late 19th century, this neighborhood boasted more Irish residents than Dublin. The infamous Five Points neighborhood of the Lower East Side, named for the five-pointed intersection of Anthony, Orange, and Cross Streets, was known for its rampant crime and fierce battles between nativist and Irish gangs, as immortalized in the book The Gangs of New York by Herbert Asbury and the Martin Scorsese film that the book inspired.

Most of these neighborhoods consisted of tenement houses – crowded living quarters built with the intention of housing as many immigrants as possible. The unbearable living conditions that the Irish immigrants endured in these tenements include poor ventilation and lighting, filthy shared outhouses (later bathrooms) for which there were long waits, basements filled with stagnant water or trash or both, not to mention the small rooms in which large families were packed. In these tenement houses disease spread like wildfire.

New Living

As the Irish population achieved upward social mobility, they began to move into other parts of the city. They moved into northern neighborhoods of Manhattan, like Yorkville, Washington Heights, and Inwood, as well as new districts in the Bronx like Mott Haven, Fordham, and Morrisania, and Brooklyn neighborhoods of Prospect Park, Marine Park, and Gerritsen Beach. Below are maps that shows the location of these neighborhoods within each borough.

| Locations in Manhattan | Locations in Bronx | Locations in Brooklyn |

|---|---|---|

Jobs for Men

Because many of the newly arrived Irish immigrants were uneducated, they sought unskilled work. Many found work in upstate New York working on the Erie Canal and other canal projects in the area. By 1818 there were 3,000 Irish immigrants working on the Erie Canal, with a total of 5,000 Irish immigrants working on four separate canal projects in 1826.

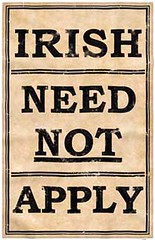

Most Irish men found jobs close to the port where they landed, especially New York City. These immigrants took unskilled jobs such as cleaning yards and stables, pushing carts, unloading ships and other dockhand jobs, or working as carpenter’s assistants, or boat-builders. They also worked in and ran factories, with dangerous conditions no better than those in railroads or coalmines. Along with railroads and canals, Irish immigrants in New York City built streets, houses, and sewer systems. They also found work in the service industry as bartenders and waiters.Irishmen often faced commonplace job discrimination, with many job posters and newspaper classifieds ending with the phrase, “No Irish Need Apply.”

A great amount of Irish men found employment as Union soldiers during the Civil War, with many of them being conscripted into service right after coming off the boat. The all-Irish 69th New York Regiment, also known as the “Fighting Irish” fought in historic battles such as those at Bull Run, Antietam, and Gettysburg. They are notable for having more combat dead than any other Union army infantry regiment, as well as having over a hundred Medals of Honor. They were highly regarded for their bravery and dependability.

Jobs for Women

Women also needed to find jobs because of the low wages and dire economic circumstances that Irish immigrants faced. They too worked in factories, particularly in the garment industry. These factories, like the ones that the men worked in, were often cramped, dirty, and dangerous. These jobs, which consisted mainly of making cotton shirts, were also low paying. Mid-nineteenth century women might get paid 6 to 10 cents per shirt, working for thirteen or fourteen hours each day. Generally this was enough time to make only nine shirts a week, which resulted in a maximum payment of 90 cents a week.

But most nineteenth century Irish women in New York City found jobs in the service industry, becoming chamber maids, cooks, and caretakers for wealthy families on Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue. The one benefit from these jobs was that they allowed immigrant women, to some extent, to enjoy higher standards of living than they could hope to obtain.

These service jobs were largely avoided by native-born New Yorkers. They were seen by Americans as degrading, the sentiment being: “Let Negroes be servants, and if not Negroes, let Irishmen fill their place.” This saying not only illustrates the view of native-born Americans on service jobs, but also the poor relations between African Americans and the Irish. Irish immigrants had to compete mainly with newly freed slaves and other African Americans for the low-end, unskilled labor jobs that other Americans did not want.