The Syrian Jewish CommunityFrom The Peopling of New York CityIntroductionIf one were to roam the streets of Flatbush and Gravesend in Brooklyn, New York, one would encounter a large community of Syrian Jews. Syrian Jews began arriving in Brooklyn in the late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries. The Syrian Jewish community in Brooklyn is largely reminiscent of the communities that once existed in Aleppo and Damascus. Many of the traditions and customs of Syrian Jews have been maintained (a strong family unit, traditional foods, etc.). In addition, there are dozens of schools (Yeshivahs) that have been built in order to serve the Syrian Jewish community. There is a large community center and plenty of synagogues that serve the community. The early immigrants were peddlers on the Lower East Side and in Bensonhurst. Today, the Syrian Jews have built up prosperous businesses and institutions and have climbed the social ladder. Let's further explore Jewish life in Aleppo and the Syrian Jewish community in Brooklyn... Diana: An Ideal CommunityIf I were to walk up and down my block, I could probably tell you who lives in each house, how many children they have (and their names) and whether or not they own a pet. No, I don’t live in some quiet village in the Midwest. Actually, I live right in the heart of Brooklyn, New York. Amidst the hustle and bustle of Brooklyn, there are individuals who choose to override the anonymity of life in New York and settle in smaller communities. Upon choosing a community in which to live, there are many factors one must consider. Each person has his or her own opinion as to what the ideal community is. In my opinion, an ideal community is a place where friendship and amicability are the norm. Children can roam the streets freely while parents are worry-free. Doors can be left unlocked. Everyone knows each other. Everyone trusts each other. People’s homes, and hearts, are always open. The whole community shares in the happiness of a wedding and mourns a loss at a funeral. Churches, synagogues and mosques can be built on the same block without fear of racist and discriminatory attacks. A community center hosts events such as carnivals, tennis matches and cooking classes throughout the year. Moms discuss their daughters’ dance recitals and fathers recruit fans to attend their sons’ little league games. Most importantly, community members feel a sense of belonging. A community is deemed a community based on its’ members. It is the responsibility of each and every one of us to establish our respective communities and help them develop into the ideal communities we envision. Be it through education or action, it is our duty to provide the best for the next generation and make the world a more pleasant place to live. Colette: An Ideal CommunityThe picture of an ideal community would be taken from an upper diagonal angle. It would show wide streets and two and three story buildings with many windows. The air would be very clear and the morning sun would be shining. There would be lots of people in the streets; parents putting kids on school buses before leaving for work on the streets while shopkeepers roll up their gates on the avenues. The community would be self-sufficient. It would have people that ensure everything is taken care of properly, from garbage collection to after school programs to keeping the peace. Everyone would know and help out everyone else with anything. There would be lots of organizations, each with a specific task, to make sure that everyone in the community has everything he or she needs and that everyone is happy. There would be a community center where all these organizations would be headquartered and where many events and get-togethers would take place so that people would stay on good terms. There would also be a publication that keeps members posted on the goings on at the community center, and in which members could bring up new projects to discuss or problems to solve. All members of the community would be polite and respectful to one another, although they wouldn’t be equals in education or financial stature. Those with more money and power would help those with less by financing and providing connections for the community’s organizations. There would be no jealousy amongst the members, as everyone would want only the best for himself and the other community members, at the same time understanding that everyone has his own place in society. They would all live alongside each other and share in joy and pain as if they were family. Most of the community probably would be related, because this ideal community would have had lots of its members living in the area for generations. The adults would work during the day, with nearly half of them running the area’s shops on the avenues. Kids would get together to play football on the streets after school, with teens watching them from friends’ porches. Eventually, many of these kids and teens would marry each other and have their own kids, thus continuing and expanding the community. Most of the new generation would stay close to home, and those who leave would start new communities in other cities that are still connected to the original one. Kyulee: An Ideal CommunityEveryone has a different view of what an ideal neighborhood should look and be like. Big fields, Little League teams, after-school programs, choices of supermarkets, great arrays of dining, movie theatre, and one or more shopping centers are a few of the admirable traits I believe a neighborhood should have. On the surface of the neighborhood, there should be neatly trimmed houses with enviable gardens, almost every house with a dog inside—viewing its daily audience through a window, or outside—in its own playpen barking at all the squirrels that pester him. To my fortune, the neighborhood that I call home is what I would define as an ideal community because it outlines my picture of the neighborhood that I always wanted to live in. Growing up with many parks, playgrounds, open fields, good schools, and the so-called ideal environment has made me appreciate the privileges and comforts that my neighborhood has to offer. Being situated in an affluent, Suburban area that is also in the vicinity of big city gives the sense that accessibility of the neighborhood plays a great role in being a great place to live. In my opinion, the most admirable characteristic of a neighborhood is its diversity and multicultural population, and also how well it suits the interests of all the people living in it, especially young children and the elderly. The more cultures that come together, the more ideas open up, people learn about each other, discovering similarities and differences along the way. However, a true community is an idea that I believe is harder to attain than an ideal environment. It is one where residents are integrated, involved in the real issues of the community, and help out one another in small and large ways alike. For example, helping out the elderly neighbor with the groceries or shoveling the snow of the driveway of a disabled person’s house shows a sense of closeness and intimacy within the people. One way in which I think the integration of a community is represented is the voter count. In the political aspect, this a very important issue, not only because it directly affects the issues of the community, but also in small-scale ways such as budget cuts. All the people in the community should be interested in the affairs. Government leaders should settle issues democratically, bring about new and better reforms, and always listen to the needs and wants of the people. I think having a good academic system plays a large factor because it brings a common interest as well as a goal to always make the community a better place. Most importantly, an ideal neighborhood is one that is not neglectful of a certain group of people or individuals, but open and caring to all the people in its community. Syrian Jews in AleppoThe Sephardic-Syrian Jewish community of Aleppo, Syria dates back to approximately 250 CE. The continuous Jewish presence in the city lasted until the end of the twentieth century, when most of the remaining Jews left the city. Throughout its long history, Aleppo represented one of the foremost urban centers of western Asia, owing largely to its strategic location on a commercial crossroad. The city was located on the main caravan routes connecting the eastern Mediterranean region and Europe. The Jewish community thrived both in affluence and religion in this illustrious city despite numerous persecutions by the Muslims. Jewish Life in Aleppo Education: The educational methods of Jews in Aleppo were similar to those of the Muslims. Muslims in Aleppo had no schools of secular education nor at the professional level. Therefore, very few Jews felt impelled to seek professional training. In order to reach the pinnacle of Jewish Aleppoan society, one would aspire to become a successful merchant, private banker, high placed rabbi or scholar. For such ends, little secular education was necessary. However, in order to communicate with Europeans, the Jews emphasized learning different languages (primarily French). Religious studies of the Torah were very important as well. Cultural Life: European culture did not pervade Aleppo. Aleppo had no theaters, no lectures, no concerts of European music etc. The cultural activities were limited to Arabic singers and Arabic theatrical groups. The Sabbath: Every Aleppoan Jewish household observed the Sabbath. Sabbath in the Jewish community meant an absolute cessation of work. Delicious traditional meals were served Friday evening and Sabbath day. The fresh bread from the Sabbath meals would then then be eaten throughout the week. Outdoor Pleasures: An important form of entertainment in the spring and fall of the year was picnicking in the numerous "bassateen" (fruit orchards). Families would stroll under the trees and would eat, drink and enjoy family time together. Note: This focus on the importance of family has remained until today. Attire: The Muslim women in Aleppo wore dark dresses with hoods-scarves that covered their entire faces. Covering the entire faces was an exclusively Muslim custom. Jewish and Christian women worse conventional, simple dresses. Most men (Muslim, Jewish and Christian) wore an "imbaazz" or "yallak", a robe reaching the ankles. Most men also wore a fez, a flat topped conical head covering of red felt. The elite Jewish merchants and wealthy community members wore European suits. Why Did the Jews leave Aleppo? The rate of Jewish emigration from Syria increased dramatically in 1907-1908 with the rise of the "Young Turks" movement. A group of Turkish army officers overthrew the Sultan, Abd-il Hamid. The new regime aimed to strengthen the Turkish empire by creating a larger and stronger army. As a result, customary exemption of Christians and Jews from military service through payment of a tax was eliminates, compelling all Syrian residents to join the army. This was a terrible prospect of the religious Jews of Aleppo because military service in a Muslim army would threaten certain religious observances (Sabbath, Kosher). In addition, 1907-1908 were years of economic distress in Aleppo. Employment shrank, merchants were ruined and there was a depression of commercial activity. When the Aleppoan Jews heard about the small community of Jews in America, who were successfully making money, they began to travel to America. Upon arriving in America, the Syrian Jews maintained a strong link to their rich heritage. Although they have mainstreamed into American society, Syrian Jews did not lose their identities. It is therefore safe to say that Syrian Jews practice a culturally pluralistic approach to life in America. Syrian Jews in DamascusThe Jewish presence in Damascus, the capital of Syria, was felt as far back as the time of the Roman Empire, when there were at least 10,000 Jews living there. Over the next two millenia, their presence is followed through brief mentions in the accounts of visitors and travelers. Despite the many political changes in Syria, the Jews remained a moderate presence, until a little over fifteen years ago, when nearly everyone left. Jewish Life in Damascus It seems that the Jews of Damascus were doing very well in the fifteenth century, as Obadiah of Bertinoro described their riches, beautiful houses and gardens in a letter in 1488 while on his way to Palestine. Not much seems to change under the Ottomans except that many Spanish and Italian Jews also settled in Damascus. Everything seems allright in the history of the Jews of Damascus until the Damascus Affair of 1840[1], in which an accusation of ritual murder was brought in connection with the death of a Father Thomas. After that, anti-semitism became either more common, or was reported on more in Syria (and around the world). Not much is written about the actual day to day life in Damascus as most of us have been out of it for a very short while. From what I've heard of the 'old country': Education: Because Jews could not work in the government or banks, Jewish students generally pursued a higher education only to become a doctor, dentist, or pharmacist. The universities were very competitive and met six days a week, including Saturdays, so most Jews didn't go to them. Because most Jews did not plan on continuing their educations, many saw no point in going to high school and began to drop out as early as sixth grade. These children went to work in the family business. Cultural Life: Most of the Jews' cultural lives revolved around Jewish holidays and celebrations of births, Bar Mitzvahs, weddings, etc. European/western culture only affected them as far as it affected the Muslim and Christian Syrians, which wasn't much. Syrian Jews did enjoy a lot of the same entertainment as the Christians and Muslims. They watched the same television, went to the same movies, and listened to the same music. I still hear about famous singers from the middle east such as the legend Umm Kulthum[2] and the very popular Nancy Ajram[3]. Attire: Syrian Jews in Damascus looked to Europe for the latest fashions. They would buy the material and have a dressmaker copy designs from catalogs that came from Italy and France. To this day, many people I know will check tags of clothes they buy because they prefer those Made In Italy. Why did the Jews leave Damascus? In 1944, after Syria gained independence from France, the new government prohibited Jewish immigration to Palestine, and severely restricted the teaching of Hebrew in Jewish schools. Attacks against Jews escalated, and boycotts were called against their businesses. For years, the Jews in Syria lived in extreme fear. The Jewish Quarter in Damascus was under the constant surveillance of the secret police, who were present at synagogue services, weddings, bar-mitzvahs and other Jewish gatherings. Contact with foreigners was closely monitored. Travel abroad was permitted in exceptional cases, but only if a bond of $300-$1,000 was left behind, along with family members who served as hostages. U.S. pressure applied during peace negotiations helped convince President Hafez Assad to lift these restrictions, and those prohibiting Jews from buying and selling property, in the early 1990's. By 1995, approximately 250 Jews remained in Damascus, all apparently staying by choice. By the middle of 2001, Rabbi Huder Shahada Kabariti estimated that 150 Jews were living in Damascus, 30 in Aleppo and 20 in Kamishli. Every two or three months, a rabbi visits from Istanbul, Turkey, to oversee preparation of kosher meat, which residents freeze and use until his next visit. Two synagogues remain open in Damascus. Today there are fewer than 30 Jews left in Syria, all in Damascus, all very old. Of multiculturalism, cultural pluralism and assimilationism. Which one most accurately depicts Syrian Jews? What do YOU think?There are three major theories used to describe the way in which immigrants should adapt to American life: assimilationism, cultural pluralism and multiculturalism. Assimilationism is the idea that as soon as immigrants arrive on American soil, they should immerse themselves in American culture and disconnect themselves from their origins. Assimilationists believe that an ideal situation would be for all the immigrant groups to completely “melt into the pot.” This notion of assimilationism was widely accepted from the end of the nineteenth century until the mid twentieth century. Immigrants arriving in America during those times worked hard to mainstream into American society. Immigrants gave up their traditional clothing, food and culture in exchange for a sense of belonging. The second theory on immigration is cultural pluralism. Cultural pluralism is the idea that there should be one dominating American culture with several culturally distinct groups within. Cultural pluralists advocate that immigrants should immerse themselves in American culture, while maintaining a connection to their original cultures as well. Immigrants should become American; yet keep certain behaviors. The third theory on immigration is multiculturalism. Multiculturalism calls for immigrants to preserve their original cultures and to remain entirely separate. There should be no umbrella American culture. Multiculturalists envision a society in which each immigrant group lives exactly as they did in their countries of origin, without any infiltration of American culture. The idea of multiculturalism is the direct opposite of assimilationism.

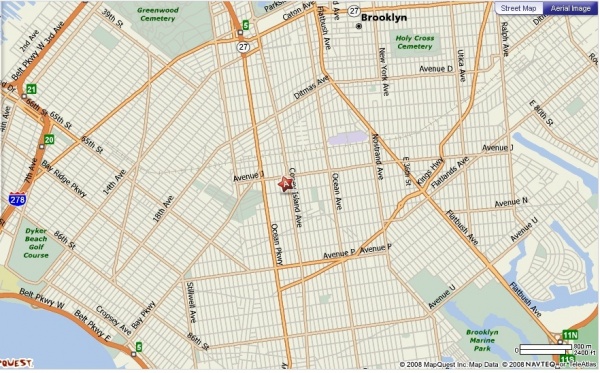

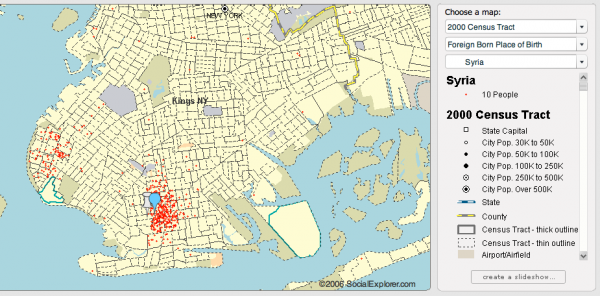

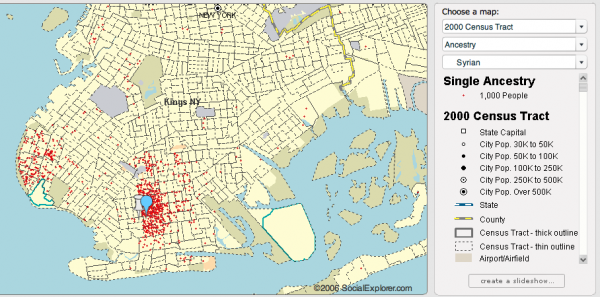

Upon analyzing the three ideas of how immigrants should behave in America, it is evident that assimilationism and multiculturalism are the two extremes, while cultural pluralism is the moderate idea in between. Throughout the course of American history, we have seen instances where immigrants have tried very hard not to change and to remain strictly multicultural, yet they were inevitably affected by their environs and have become cultural pluralists. For instance, there was recently an upheaval in the Jewish Hasidic community (one of the most tight knit communities) because a popular singer incorporated an American secular tune into his song. The same is true in the opposite direction. There have been immigrant groups who have chosen to completely assimilate; yet were unable to (language barrier, race) and have therefore become cultural pluralists as well. The Eastern European Jewish immigrants of the early twentieth century are prime examples of people who wanted to assimilate but couldn’t because of various factors (illiteracy, non-English speaking). Today, I believe New York City is largely culturally pluralistic. There certainly is an American culture of apple pie and baseball games that is felt by all. Yet within this scope of American culture lie dozens of subcultures. There are Chinese, Italian, Israeli and Turkish restaurants. There are churches, mosques and synagogues. There are neighborhoods such as Chinatown and Williamsburg. Individual cultures have been maintained amidst the larger American culture. Syrian Jews in BrooklynThe Jews of Syria arrived in America with next to nothing, as most had gotten here illegally. They started out like many other immigrant groups, on the Lower East Side: Excerpted from The Forgotten Jews of the Lower East Side: Greeks, Turks and Syrians[4] by Shelomo Alfassa / April 8, 2008 Written for the Gotham Institute, New York City The Syrian Jews, much more substantial in number than the Greek Jews, had arrived in New York mainly from the cities of Aleppo and Damascus, where many had existed since ancient times. While some Syrian Jewish families posses ancient roots, others have a history of arriving in Syria following the 15th century Inquisitions, although these latter Jews would soon lose their Spanish tongue and assimilate into the greater society. Syrian Arabic speaking Jews had arrived at Ellis Island because over several decades, their economy had turned sour following the opening of the Suez Canal which destroyed the overland caravan routes. In addition, anti-Semitism reared its ugly head when Syrian Arabs blamed the Jews for helping to build the Canal which eventually destroyed the local economy, and this was compounded when the Turks demanded that young Jewish boys serve in the Army. Some of the earliest families to arrive in New York were the Beyda, Blanco, Chabbat, Bracha and Sitt families from Aleppo. (Diana: The Chabbat family, later spelled Chabot, is my great grandfather's family name!) The heart of the original Sephardic colony (as it was known to the locals), was generally in the area sandwiched between Chrystie Street to Allen and Delancy Street to Grand. Living in tight enclaves, they could feel as if they were not completely uprooted from their past. There, among the rumble of the Second Avenue elevated train that once clamored down what is today the west side of Allen Street, they frequented kavanes (Turkish coffee houses), ate Arabic, Balkan, Greek and Turkish foods, sung their old songs, and spoke in their native languages. Kavanes and Sephardic grocery stores once dotted the Lower East Side. Mr. Habib had his Sephardic grocery store on Rivington; Mr. Cohen on Stanton; Mr. Massod has his coffee house on Allen, so did Mr. Crespin and Mr. Namir. When Rabbi Dr. Nissim J. Ovadia escaped the Nazis and arrived in New York City in 1941 to become Chief Rabbi of the Central Sephardic Jewish Community of America, over 1,500 people came to greet him. Rabbi Ovadia gave a stirring appeal for unity to which the Jews from Aleppo and Damascus, now living in New York, were responsive to. Joining Rabbi Ovadia in the effort of communcal unity was Issac Shalom, a leader of the Syrian community, who in 1944 went on to form the Magen David Federation, the pre-cursor to the Sephardic Bikor Holim and other major New York based Sephardic charitable organizations. At the dinner was Hakham Jacob Kassin, Chief Rabbi of the Syrian community, who addressed the audience in Hebrew and called for further unity of all the Sephardim in New York. On Eldridge Street, Turkish Jews established a community center which was visited by all of the Sephardic Jews. This included members off Congregation Shearith Israel, members of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue which was uptown, a community of "distant cousins" which had originally settled in New York City in 1654 by refugees fleeing the Portuguese Inquisition. Rabbi Dr. David De Sola Pool, then the assistant rabbi of Shearith Israel, on more than one occasion slept on the Lower East Side in order to help the Syrian community have proper services in their tradition. The Greeks, Turks and Syrians all had their own schools, yet, Greek Jews were known to attend Syrian schools, Syrian Jews went to Turkish coffee houses, and Turkish Jews attended Greek synagogues. The initial immigrants were extremely poor and most jobs consisted of selling fruit, candy, peddling small items, or shining shoes. Eventually, they fell into better jobs such as seamstresses, clothing pressers, and factory workers. They would go on to develop community clubs such as the Dardanelles Social Club and Oriental American Civic Club as a means of supporting each other. They experienced a significant degree of prejudice from the German and Russian Jews which did not understand their Greek, French, Spanish, or Arabic languages. Though having no formal education or wealth, these immigrants went on to do well for themselves. They developed newspapers in their languages, opened small business, and were even able to save money and donate back to their communal organizations. By the mid-1930's, New York and the rest of the country was beginning to recover from the Great Depression. Both opportunity for greater education and jobs were becoming available, and soon New York would have its first Sephardic Lawyer, Dentist, and Teacher. Many families (even the poorest ones) sent money to their families back in the old country who were still experiencing poverty. Many Turkish families moved north to Harlem, and others east to New Lots and Coney Island in Brooklyn. On the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, there was a thriving Sephardic colony, synagogues, Jewish schools and kosher butchers. Syrian Jews moved uptown too, but most went to Bensonhurst, and much later to Ocean Parkway in Midwood. Neighborhood StatisticsI researched the zip code in which I live, 11230, and came up with interesting information. Since this zip code has a large Jewish population(view below:Map of Religion: Jewish) and many Jewish children attend yeshivahs, the number of students attending private schools is disproportionate to the number of New Yorkers attending private schools. Private vs. public school enrollment: Students in private schools in grades 1 to 8 (elementary and middle school): 5,419 Here: 48.9% New York: 14.0% Students in private schools in grades 9 to 12 (high school): 2,424 Here: 42.5% New York: 13.2% Students in private undergraduate colleges: 2,913 Here: 48.4% New York: 38.2%

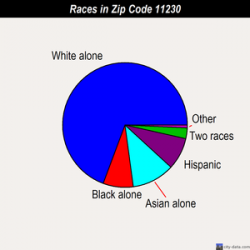

White population: 64,939 Black population: 7,346 American Indian population: 250 Asian population: 9,901 Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander population: 44 Some other race population: 3,365 Two or more races population: 3,088

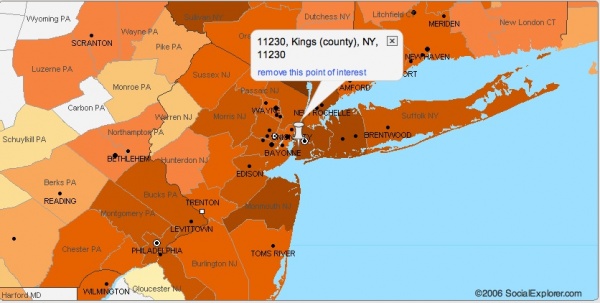

The bottom map is a map of Jewish residents of zip code 11230. The dark brown color indicates about 25%-31%.

11230: $575,226 New York: $258,900

11230: $10,609 New York: $4,439

This zip code: 47.3% Whole state: 20.4%

Ukraine: 16% Russia: 14% Pakistan: 9% Haiti: 5% China, excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan: 5% Other Eastern Europe: 4% Poland: 4% For more information on zip code 11230 and interesting statistics please visit: [11230 Zip Code Detailed Profile]

Syrian Jews mark 100 years in U.S.ALANA B. ELIAS KORNFELD Jewish Telegraphic Agency NEW YORK - One hundred years after Syrian Jews began arriving on U.S. shores, the community in many respects still resembles its close-knit forebears from Damascus and Aleppo."We are not celebrating the fact that we arrived in this country, but we are celebrating the fact that we came and remain intact so we see grandchildren acting the same as great-grandparents," says Rabbi David Cohen, whose Sephardic Renaissance group organized a recent cantorial concert in Brooklyn to mark the community's 100th anniversary. The event, which honored three patriarchs of the Syrian community - Sam Cattan, 96, Moses Tawil, 89, and Abe Cohen, 91 - was the first of many events planned for this year to mark the group's centennial. Joey Cohen and Shirley Fallas, young Syrian Jews engaged to be married, have embraced the communal continuity lauded by Cohen. "Family values are passed on from generation to generation and people like to keep the same values within the community," Cohen said. And it is this message that the Syrian community - which estimates its population in the United States at more than 50,000, mostly in Brooklyn and Deal, N.J. - aims to share with the rest of the Sephardic community and the Jewish community at large. "We have similar situations in some Iranian and Bucharian communities, who are well organized between themselves,"says Mike Nas-simi, chairman of the board of the American Sephardi Federation. The hope of the federation, he says, "is sometime in the future to bring all these individual communities under the umbrella to make them role models for other small communities. The Syrian community helps to keep the Sephardic traditions alive because they are a successful community and are well connected." The Syrian community first arrived in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the early 1900s before moving to Brooklyn's Bay Parkway section. Now, Syrian Jewish life revolves around the main hub of Ocean Parkway, where the community built its main synagogue, Shaare Zion. But unlike other Sephardic communities that have not stayed intact, the Syrian community remains tight. Charles Anteby, the 44-year-old public affairs director of the Sephardic Food Fund, says this has to do with the fact that the Syrian community boasts many organizations support-ing its life and contributing to its vitality. Syrians say there is very little intermarriage in their community and a low divorce rate. In addition, much of the community continues to live in single-income marriages in which the man is the wage earner. Because of the importance placed on being with family in the Syrian tradition, many have chosen to live within walking distance of their relatives. "My whole family is Syrian," Fallas says. "It's wonderful, I love it. Everybody stays very, very close and sort of has their hand behind everybody's back, watching out for each other." The community also stays close together because of its strong connection to Judaism. "We are all considered Orthodox," Anteby says. "There are no conservatives and no liberals, so im-mediately you have the issue of proximity to synagogues and because we have our own praying styles, we're most comfortable in our own synagogues." Cohen also cites the Syrian commitment to education as among the reasons the community has thrived. They have set up about 22 yeshivas. In a room filled with around 2,200 members of the Syrian community eagerly waiting to begin the anniversary celebrations, Mickey Kairey emphasized just how strong that connection is. "There isn't a community on this planet as good as ours," he said. "We never get tired of looking at each other. Group MembersThe following individuals were instrumental in the development of this wiki page. For access to more information and to our individual stories and research, please explore the following links... Diana Haddad: User:Dianahaddad Colette Salame: User:ColetteSalame Kyulee Seo: User:Kyuleeseo |