Little Bohemia

From The Peopling of NYC

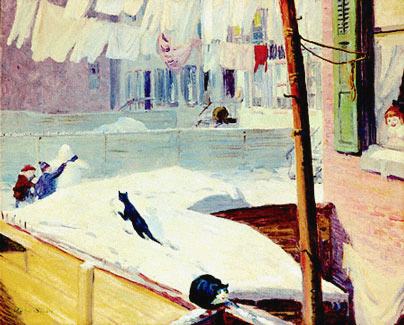

Greenwich Village, New York's Bohemia, is a rainbow blur of colors, a rush of silver creativity, still maintaining its late nineteen-sixties counter-culture personality. Tourists snapping photos with their new chrome digital cameras, students rushing, bags slung over their shoulders and large lattes and cell phones in their hands, locals looking laboriously through bright green peppers at the grocery store and ever-paparazzied celebrities shopping, all walk the same streets. What have these streets seen; what have they felt, as each year faded into New York’s horizon, another strip of fuchsia in the navy sky? Did the Beat Generation shake them with its reviving pulse? Did the riots leave them feeling raw and alive? Have they witnessed the same story being written generation after generation, a sense of pride swelling in their cemented hearts?

[edit] New York's Bohemia

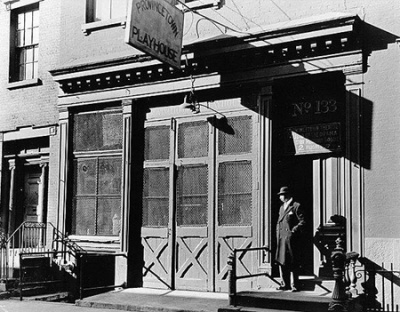

Counterculture's roots were firmly planted in the early 1900s, where avant-garde ideas in literature, art, sexual experimentation, freedom and politics blossomed. Greenwich Village was known as "an American Bohemia or Gypsy-minded Latin Quarter" (Stonehill 11), and although many of the literati and artists were relatively unknown, great literature such as James Joyce's Ulyesses was serialized by the West 8th Street Little Review (discontinued shortly afterwards because of "obscene literature"), as well as John Reed's Ten Days that Shook the World and Willa Cather's My Antonia. 133 MacDougal Street, home of the Provincetown Playhouse, was where the works of authors such as Eugene O'Neill, who was "intensely romantic and tended to idealize women" were performed (Stonehill, 32). The Provincetown Playhouse's decade of success, from 1915 to 1925, inspired the opening of many "little theaters" acrosse the country. Also on MacDougal Street were the Minetta and the San Remo, drinking places where Maxwell Bodenheim, "the great lover of the Village," who caused girls to commit suicide when he called their poetry "sentimental slush" (Stonehill, 36).

After WWI, the young writer Malcolm Cowley came to Greenwich Village with other artists, “without any intention of becoming Villagers.” They chose the area because “living was cheap,” and “friends had come already (and written letters full of enchantment),” in New York City, the most attractive city for young artists. The Village symbolized eccentricity and folly, a place for silly, strange artists with an ideological, often revolutionary, bent. It stood upon the principles found in similarly conceived neighborhoods in Germany, England, Russia, and France, whence it originated. This type of life was glorified in Henry Murger’s Scenes de la Vie de Boheme. Villagers would open their own small businesses in the area while simultaneously pursuing their artistic ambitions. If the business would succeed, it would be turned into a chain, with branches in other neighborhoods (and perhaps even other cities). If the artistic career would take off, the artist would move to wealthier, more conventional neighborhoods, and would adopt a more mainstream lifestyle.

There were eight main values of the 1920s bohemian set: individualistic development of personality, unencumbered by conventional standards and expectations; the ideal of complete self-expression in art and life; “paganism,” or worship of the body as the ultimate instrument of love; living for the moment, enjoying what one can when one still can; liberty; female equality; psychological adjustment, which is to say that one must remove repression and inhibition to be happy in any situation; and relocation to a freer society (like that of France). Cowley believes that the “revolution of morals” helped along by the Village culture was inevitable anyhow, and even if the Village hadn’t existed, this revolution would have taken place. Pleasure seeking and the underworld had always existed. The war, which took fathers to war and mothers to work, left the young largely un-chaperoned, so they could experiment and discover new things and each other. The Prohibition era sensationalized vice in a way it never had been seen before, making it attractive and exciting. The booming economy allowed for the pursuit of pleasure, and Sigmund Freud’s theories normalized what had previously been considered abnormal and evil.

That is not to say that the Village and the ideals at its foundation played little or no role. On the contrary, the counterculture of lower Manhattan shaped this new social reality, making nonconformity normal and acceptable, even standardized. This influence reached all of American society in a deeply profound way. Tourists even then flocked Greenwich Vilage in herds to the point that the Village's commerical success raised rents so high, paradoxically making it difficult for the Bohemian artists to remain there. The Village itself died, however, when the people who had made it what it was moved away, and the central institutions of the culture were weakened or closed.

The new generation of Villagers, reports Cowley, were a disappointment to their predecessors. They were not bohemians, but conformists; not idealists, but bland. The old generation bemoaned the paucity of individuality, creativity, and freshness in intellectual and artistic life, and their successors failed to do their part to correct that. Because the Village was now drained of its ideals and principles, artists and intellectuals, like Cowley himself, became disillusioned and became expatriates. The more open society of France beckoned.

Article about Arch Conspirators

[edit] The Beats in the Village

"The so-called Beat Generation was a whole bunch of people, of all different nationalities, who came to the conclusion that society sucked ." - Amiri Baraka

"Saturday I plan to go down to Greenwich Village with a friend of my who claims to be an "intellectual" and knows queer and interesting people there. I plan to get drunk Saturday evening, if I can." -Allen Ginsberg, 1943, letter to brother Eugene.

Creativity's brilliance fireworked again in the Village in the late 1940s making it "as close as it would ever come to Paris in the twenties [...] In Washington Square would be novelists and poets tossed a football near the fountain and girls just out of Ivy League colleges looked at the landscape with art history in the eyes. People on the benches held books in their hands." (Anatole Broyard, Kafka was the Rage) These writers including Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burrough, Neil Cassidy, Gregory Corso, and Peter Orlovsky were members of the prominent Beat "Generation", although the term also refers to counter-culture radicalness. Although in a 1983 interview, Allen Ginsberg said "there never really was a Beat Generation, there was a group of friends[.]" (Laurldsen and Dalgard, 23) Ginsberg also considered himself "basically a Russian poet, put into an American scene." (Laurldsen and Dalgard, 28) Most of the literary world disdained the Beats and considered them "know nothing," though many aspiring writers journeryed to the Eighth Street Bookshop, where writers like Allen Ginsberg, lived and were respected.

Most of the Beat Generation served in World World II and the Korean War. They were mostly middle-class college students who rejected conventional social standards. They were sexually promiscious, denounced consumer ethics, were drug addicts, were prostitutes, and they were outcasts. Perhaps the Beats are defined by their non-conformist behavior and thier influence was proportionally unequal to their small number. By the mid-1955, the Beats had acheived celebrity-status though the art and literature scene began moving from Greenwich Village to the East Village. Although the Beat Movement began to decline in the late 1950s, the Beats were the predecessors of the Hippies and the Yippies.

Silent Footage of the Beats

Interview with Jack Keroac

Allen Ginsberg in Greenwich Village: His Influences and Influence

In the 1970s, the "gay power" movement burst onto the scene as the most controversial of all the civil rights crusades. However, it has been said that the original catylyst for the activity was the widespread and revolutionary effect of Dr. Alfred Kinsey's study on "Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male" (also known as "The Kinsey Report") published in 1948. This groundbreaking research helped to create an urban gay subculture and gave homosexuals a definitive sense of belonging to a community. In the years following this publication, two major gay organisations were formed--The Mattachine Society in 1950, and The Daughters of Bilitis in 1955. Both groups actively protested against discriminatory policies and were instumental as the first chapter of the gay rights movement.

In 1969, on the evening of Friday, June 27th, what is now considered to be the official beginning spark of the gay rights movement was set alight, both literally and figuratively. At The Stonewall Inn members club on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, it was not just another night. The recent death of American cinema and gay community icon Judy Garland on the Monday of that week, and her burial on that very Friday, had prompted the holding of a wake at the Stonewall. In fact, it is alleged that "Somewhere Over the Rainbow" was playing on the jukebox when the police showed up.

At first, no one was particularly peturbed as raids by the New York City police were in fact routine, and the authorities usually just asked to see the manager's liquor license, frisked a few patrons for drugs and made general threats. However on this night, the police took it one step further and attempted to arrest some drag queens and a lesbian, forcing them kicking and screaming into the paddywagon that was parked in the front of the club.

It seems that the unjustified arrests, together with the high-strung emotions that were already in the air due to the events of the week clashed and exploded as the gathering crowd became more and more rowdy, jeering the police and making obscene gestures. The situation quickly escalated into a full-scale riot. Patrons from the Stonewall threw bottles, stones, beer cans and Molotov cocktails which set the bar ablaze. They also attacked police cars and the reinforcements. Rioting continued into the next day, June 28th, and the police ended up battling scattered crowds and clusters of angry protesters in numbers upwards of 2,000 people. Overnight, gay power grafitti slogans had been spray-painted on walls throughout Greenwich Village and Lower Manhattan.

Allen Ginsberg, a central Greenwich Village figure, was quoted in The Village Voice as saying,"You know, the guys there were so beautiful. They've lost that wounded look that fags all had ten years ago." The Stonewall Inn Riots galvanised the formation of the Gay Liberation Front in New York City in July 1969, and promoted activism against discrimination from the authorities and in the media.

The History of Stonewall with Varla Jean Merman

Our revolution didn't start with Stonewall. African-American lesbian elders tell the tales of gay New York life in Harlem, Brooklyn and the Bronx before the world-altering Stonewall rebellion. In this clip they recall, raids and suffocating laws and racial discrimination faced within the gay community.

For more information about The Stonewall Inn Riots:

"Remembering Stonewall":Interview Transcript

The Stonewall Veterans Association

The Stonewall Inn Riots on Wikipedia