From The Peopling of New York City

[1]

Introduction

Through the Years: Racetrack to Speedway to Co-op Complex

The Sheepshead Bay Racetrack [2]

The Sheepshead Bay Speedway[3] The narrative that you are about to read tells the tale of a seemingly unspectacular street in Brooklyn that surprisingly has a certainly spectacular history, often untold or even unknown until now. What started as a project to research a street near and dear to my heart (after all, I do live here), blossomed into a sort of obsession to find out everything I could about what stories my street held secret. The narrative that follows will hopefully give you a sense of where my obsession led, how I was able to conduct my research, and why I feel that the history of my street is worth telling. From a racetrack to a speedway to a co-op complex, I have found that my street has undergone tremendous transformations caused by important political and cultural discussions and movements, been traversed by interesting and oftentimes unscrupulous people, and ultimately led into its final form by a vast social shift caused by the return of soldiers from war. A case study in the peopling of New York, The Secrets of Nostrand Gardens, provides insight into some of the many factors that have forced or at least encouraged great amounts of change not only in a particular city or borough of New York, but also on a particular street.

Present Day Haring Street: Nostrand Gardens THE SECRETS OF NOSTRAND GARDENS: Gambling, Speculation, and the Drive for Development on Haring Street

Greenery like these bushes, now adorns the aptly named, Nostrand Gardens

A tree grows in Nostrand Gardens When people walk down Haring Street between Avenue X and Y in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, they might enjoy the greenery, take a look at the grandness of the apartment buildings, and think little else about it. Sure, this street is beautiful, with its many trees that canopy over parked cars, bushes and flowers hiding squirrels and cats chasing after each other, and a multitude of birds chirping at almost every hour. Indeed, the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens chose this street as a semifinalist for the greenest block in Brooklyn during 2005, and gave it honorable mention in 2008. Beyond the park-like atmosphere, six towering six-story apartment buildings, which house 348 families, catch any observer’s eye, particularly when many American flags hang from windows on the 4th of July and Veterans’ Day, or when hundreds of Christmas lights and Chanukah menorahs glow during the holiday season. What most observers overlook, however, is the street’s unique history, and the many stories that can be told from a structure no longer seen and rarely heard about which the street now covers.[4]

Current Day Nostrand Gardens

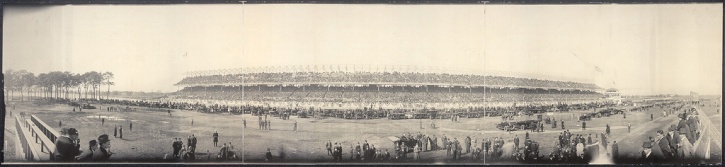

I have lived my entire life on Haring Street between Avenue X and Y, in one of the six apartment buildings (which now contain privately owned co-op units), Yet, I neither knew nor thought to ask about how or when the buildings were built and for what reason. I also had absolutely no knowledge of anything existing on this street before “my” buildings were erected. From research I have found that the land on which my street was built was once part of the Sheepshead Bay Racing Track and later the Sheepshead Bay Speedway. In 1880, a group of very wealthy Brooklynites drafted plans to build the Sheepshead Bay Racing Track, which officially opened in 1884. By skimming through the New York Times, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and other newspapers, I found hundreds of articles containing the racing information for each week as well as details about how much money people won. These articles also reveal a successful horse-racing track with a large fan base, and which also reflected on much of what was going on socially and politically at the time in Brooklyn.[5]

Horses jockeying for position on the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack[6]

In an 1892 New York Times article, this track and others, including the Brooklyn Trolley Club track, were shown to be frequented by such politicians as Mayor Grant and State Senator McCarthy. Grant was “extremely popular” at the track and for this reason, “there [was] not a horse owner, a horse trainer, or a jockey of consequence but ha[d] an acquaintance with the Mayor, and [was] glad to give him a chance to back a horse that [was] sure to win the race that [was] to be run.” The senator, McCarthy, usually sat near the judges’ stand and frequently sat with horse-racing “advisers” who knew the ins and outs of the races. Whether these politicians or their colleagues were simply expressing their love of horses, trying to gain votes by making public appearances, or receiving under-the-table gambling tips from those in the know, the race tracks of Brooklyn do not appear to have come under much fire by local governments or most of the common people for that matter, looking to stop the “immoralities” of gambling. [7] According to Bennett Liebman in his “Horseracing in New York in the Progressive Era”, although the period between 1890 and 1910 came at the time of the Progressive Movement in which more and more people were looking to get rid of vices in society, the government generally protected New York’s racetracks at the time. He argues, “[From] the early 1890s to the early 1910s, the courts in New York regularly ruled in favor of horseracing interests…[and they] protected the racetrack industry from a series of attacks from progressive reformers and other anti-race horse gambling forces.”[8]

Video of the Sheepshead Bay Speedway from 1897

[9]

The immorality of gambling for women, however, was another story. Long before women were enfranchised with the right to vote in 1920, issues of women’s rights brewed on the sidelines of the “Sport of Kings” in Brooklyn. The same 1892 New York Times article discusses some of the racetracks beginning to secretly allow women to gamble, and the public is shown to have not condoned this at all. According to the article, a man at the track after hearing about women gambling had said, “By heavens! That is carrying betting too far.” The article goes on to argue that, “This man…voiced the opinion of all the men who [had] been at the track, as well as of the ladies…[who feared] losing all self-respect.” Whether this article was written by someone who was completely biased against women having rights and therefore lied about what people thought about women gambling, or whether his reporting was actually true, the Brooklyn race tracks certainly brought out issues that were important and controversial at the time.[10]

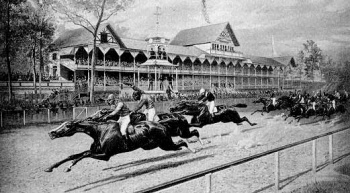

Cars racing on the Sheepshead Bay Speedway[11]

A plane takes off from the Speedway as onlookers wish farewell[12]

Although the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack provided a place for some of the cultural and political discussions shaping the nation at the time, in 1915, the Whitney family purchased the track and converted it into the Sheepshead Bay Speedway and replaced horses (then the “sport of kings”) for the automobiles that soon raced for money.[13] A New York Times article, “World’s Largest Sports Arena,” discussed the building of the speedway and bursted with excitement about the prospects of such a grand infrastructure. Reporting on the recent sale by the Coney Island Jockey Club to the Whitneys, the Times argued that the Speedway would “be the most comprehensive, as well, as by far the largest, public arena for outdoor sports in the world,” including car racing, football, track meets, baseball, tennis, and even aviation at the massive complex.[14] Although not all of these grand plans came to fruition, and the speedway’s life lasted for fewer than five years, the speedway was quite successful.[15] However, Henry Whitney sold it in 1919 to the Joseph Day Real Estate Company in order to pay off his son’s gambling debt. Between 1919 and 1922, developers, including Knapp, Batchelder, and Haring, built streets and small homes where the racetrack and speedway had once rested, naming the streets for themselves.[16]

Map from "Desk Atlas Borough of Brooklyn Vol. 4", published by E. Belcher Hyde Map Company in 1929, depicting Haring Street between Avenues X and Y. The map shows 7 lots portioned out, but no infrastructure at all on my street[17]

Picture taken at corner of Voorhies Ave. and Haring Street in 1938 showing the emptiness of the area before Nostrand Gardens was built [18]

After my street was developed, not much else took place on the land between 1919 and the 1950s. According to the “Desk Atlas Borough of Brooklyn”, by 1929 the land on Haring Street between Avenues X and Y had lots drawn out, but contained no buildings, homes, or stores. Seven lots in all were apportioned out, with the biggest lot dimension being 500 by 105 feet and the smallest being 90 by 90 feet. A very interesting element of the atlas map of my street shows that the actual pavement of the street was labeled as “streets opened but not improved,” whereas the next street over (Nostrand Avenue between X and Y) was labeled as “streets opened and improved”. Evidently my street was not as heavily traversed because of a lack of infrastructure as Nostrand was (which still sees much more traffic than my street), and therefore did not need to be paved as well.[19] In continuing to figure out the mystery of what existed on my street between 1919 and the 1950s, I have found a photograph from 1938 depicting the corner of Voorhies Avenue and Haring Street (a location very near my street). The photograph shows no infrastructure anywhere in the near vicinity and the road looks to be made up of mostly dirt.[20]

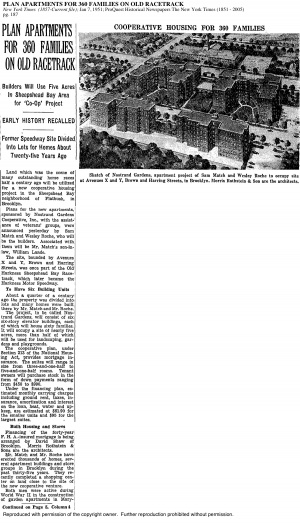

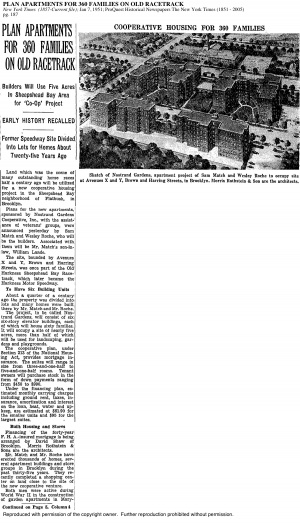

Page one of 1951 New York Times article discussing the plan to build Nostrand Gardens apartment complex with a sketch of what the proposed complex will look like[21]

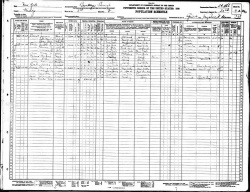

Not until the early 1950s, it appears, approximately 32 years since the last cars raced on the Speedway, did anything on my street begin to “happen” again. The building complex that contains six, six-story buildings was dreamed up and set to be completed around 1951. News accounts describe a proposed plan for Nostrand Gardens (the name of the building complex) to be built on Haring Street, between Avenues X and Y. The best information about the building of the complex comes from a New York Times article of January 7, 1951, that details much of the information about how the project came to be, and what had been going on around the neighborhood prior. Before I had read this piece I was not completely sure whether the old Sheepshead Bay Racetrack and Speedway had actually rested on my particular street. Not only could I not find specific parameters for the Racetrack and Speedway which included Haring Street between Avenues X and Y (because the street had not been established until the Speedway was closed and the land was sold), but I had also never seen any sign or artifact of it anywhere on or around my street. The only source I had (not a very reliable one) was from my uncle. During a recent family gathering, I off-handedly brought up the project I was doing for this class. My uncle, along with my mother, had grown up in the Sheepshead Bay Projects (located within shouting distance from the buildings on Haring Street), and he seemed to have a vague recollection of hearing an interesting tidbit about earlier life on now - Haring Street. He told me that one day when he was a little boy, a man told him that Haring Street had once been home to horseracing. I took this information with a grain of salt, until I found the aforementioned article from January 7, 1951. The article described plans for building, and claimed that an apartment complex would rest on, “Land which was the scene of many outstanding horse races half a century ago.” Moreover, the article claimed that the land, “will be utilized for a new cooperative housing project…” The developers, Wesley Roche and Sam Match had developed other homes around the neighborhood and also a local shopping center (which still exists).[22] According to the 1930 census, Roche was born in 1896, and had a wife and one child. At the time that the census was taken he listed his occupation as “contractor” and his industry as “builder”, and his success as a developer also allowed him to have a servant from Norway by the name of Johanne Barth.[23]. The apartment complex that Roche and Match built, called Nostrand Gardens, was promised to include a parking garage and gardens, was slated to take up about five acres of land, and had unit purchase prices between $450 and $990. Roche and Match were cited as saying that they had decided to build on this particular land because of its proximity to shopping, transportation, and schools (Shellbank Junior High School, and the soon to open P.S. 52).[24]

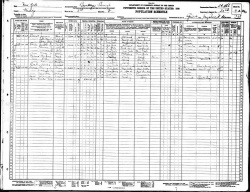

1930 census report in which Wesley Roche, one of the developers of Nostrand Gardens, is shown to be married with one child and a servant, living in New York, and working as a "contractor" in the industry of "building"[25]

The article also reveals a great deal about co-op building in New York City during the Post-WWII period, particularly its discussion of Section 213 under the Housing Act. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Development, the Housing Act, originally passed in 1950 (soon before plans began for Nostrand Gardens), contained a section specifically focused on co-op buildings. According to HUD, “Section 213 insures mortgage loans to facilitate the construction, substantial rehabilitation, and purchase of cooperative housing projects. Each member shares in the ownership of the whole project with the exclusive right to occupy a specific unit and to participate in project operations through the purchase of stock.” The purpose of the act was to protect companies seeking to build co-op buildings, and allow for units to be sold for somewhat less because they were backed up by the government.[26]

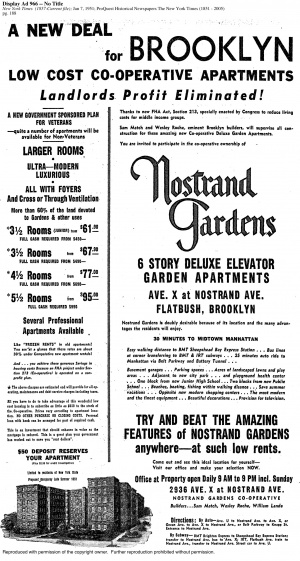

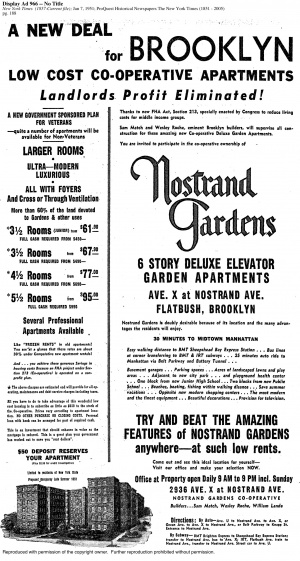

Advertisement for Nostrand Gardens describing it as low-cost housing under Section 213 of HUD. It also gives specifics about pricing, location, amenities, and gives a sketch of what complex will look like[27]

In getting a sense of the allure to potential customers that these co-ops created, we come to an advertisement for the Nostrand Gardens complex. The advertisement promised an opening in the summer of 1951, and claimed that the project was a, “New government sponsored plan for veterans…[with] quite a number of apartments…available for Non-Veterans.” Section 213 of the Housing Act was billed as a way for veterans to receive less expensive housing (after World War II), and evidently was used as a way to advertise a “good deal” for other people who wanted housing. The advertisement went on to promise “frozen rents” and claimed that the rates were around 30% less than other new apartment units (maintenance rent ranging from $61.90 to $95.00 depending on number of rooms). Most tellingly, in the advertisement’s attempt to play up the Housing Act and Section 213 it argued that, “you achieve these generous Savings in housing costs Because an FHA project under Section 213 (Co-operative) is operated on a non-profit plan,” and, “This is a great plan your government has worked out to save you ‘rent dollars’.” At the time, it must have been advantageous to make claims that the government had their hand in creating good deals for people, because there must have been a greater trust in and patriotic feeling towards the government after the U.S. had been victorious in WWII. Claiming that “Landlords profit [will be] eliminated,” the advertisement further played on the anger that many Brooklynites, and Americans for that matter, had against wealthy owners (a feeling that resonates even stronger today). The advertisers seem to have been banking on the fact that people would be more willing to pay affordable amounts to the government, than pay a “greedy” owner seen as raking it in.[28]

Another interesting New York Times article from June 17, 1951 claimed that the Roosevelt Savings Bank (which still exists nearby on Avenue U) had given a $3,165,800 mortgage loan so that the buildings could be built. Roche and Match were said to have had claimed that as of that time most of the apartments had already been sold…not a bad way to convince the bank to give them a loan and to convince others to want to live there.[29]

Added bonus of co-op: A beautiful playground. I have spent countless hours playing basketball here

Erecting co-ops in New York City or in Brooklyn for that matter, was no new thing at the time, but after WWII, more and more began to be built. According to Gerald Sazama in his, “A Brief History of Affordable Housing Cooperatives in the United States”, the earliest housing cooperative in the United States was built in Brooklyn in 1918, while the “The first relatively large scale affordable housing cooperatives were made possible by the New York State Limited Dividend Housing Companies Act of 1927…which provided to corporations significant property tax exemption for 50 years, and authorized use of the right of eminent domain to make possible the acquisition of suitable sites for investors building apartments for middle-income families.” The post-WWII period saw a boost in the number of co-ops built because affordable housing was needed for the Baby-Boom generation. According to Sazama, New York became the hotbed for building these complexes as “about one-fourth of the nation's affordable housing cooperatives were built in New York City from 1945 through the 1960s, under various financing arrangements available only in New York, and with sponsorship by trade unions and the State.”[30]

From its start as a cooperative complex backed by the government, Nostrand Gardens has continued to be on the cutting edge of housing precedent. Not always the right edge, however. In a 1995 court case, Nostrand Gardens Co-op v. Howard, the complex was taken to court after a tenant complained about loud noise emanating from his neighbor’s apartment in the middle of the night. Nostrand Gardens lost the case, because the court ruled that, “the co-op breached the warranty of habitability by failing to remedy, after repeated notice,…[the] excessive noise.” The complex was ordered to return fifty percent of the plaintiff’s rent, and the case set a precedent for co-ops’ noise responsibilities. The result of the trial proved to be quite controversial, however, because it placed complete liability for the noise issue on the co-op itself, rather than on the actual tenant who was creating the problem.[31]

Endnotes

- ↑ http://www.rumbledrome.com/sheep.html

- ↑ http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/44/No_Known_Restrictions_Horse_Racing,_Currier_&_Ives_Lithograph,_1890_(LOC)_(489398731).jpg

- ↑ http://www.rumbledrome.com/images/sheep1.jpg

- ↑ Brooklyn Botanic Gardens, “Greenest Block in Brooklyn Contest 2009: A Friendly Competition For Residential and Commercial Blocks in Brooklyn,” http://www.bbg.org/edu/greenbridge/greenestblock/2008/winners_all.html.

- ↑ New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, “Sheepshead Bay Piers,” http://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/B393/highlights/7830, [hereafter NYCDPR].

- ↑ http://www.westland.net/coneyisland/articles/images/con-horseracing.jpg

- ↑ "GOSSIP OF THE RACE TRACKS: PUBLIC GAMBLING BY WOMEN DISAPPROVED OF AN INJUDICIOUS EXPERIMENT THAT WILL SURELY LEAD TO TROUBLE FOR THE JOCKEY CLUBS -- LUCKY POLITICIANS WHO GO TO THE RACES ALMOST DAILY," New York Times (1857-Current file), September 18, 1892, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed May 8, 2009), [hereafter NYT Gossip].

- ↑ Gerald Sazama, 1996. "A Brief History of Affordable Housing Cooperatives in the United States, "Working papers 1996-09, University of Connecticut, Department of Economics. (accessed May 8, 2009).

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLdB6KNXzHY

- ↑ NYT Gossip

- ↑ http://www.rumbledrome.com/images/sheep10.jpg

- ↑ http://www.air-racing-history.com/PILOTS/images3/13.jpg

- ↑ NYCDPR

- ↑ "WORLD'S LARGEST SPORT ARENA: It Will Be on the Old Sheepshead Bay Race Track and Will Seat Three Times as Many Persons as the Huge Yale Bowl," New York Times (1857-Current file), May 2, 1915, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 1, 2009).

- ↑ NYCDPR

- ↑ “Answers From ‘Brooklyn By Name’ Authors Part 1,” New York Times, July 3, 2007, http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/03//?scp=1&sq=Answers%20From%20%E2%80%98Brooklyn%20by%20Name%E2%80%99%20Authors,%20Part%201&st=cse.

- ↑ “Desk Atlas Borough of Brooklyn Volume 4 Sections 20-25,” E. Belcher Hyde Map CO., Inc, 5 Beekman St., N.Y.C., p. 243, Brooklyn College Special Collections, [hereafter Brooklyn Atlas]

- ↑ http://iii.brooklynpubliclibrary.org/articles/11229030.8373/1.JPEG, [hereafter library photo]

- ↑ Brooklyn Atlas

- ↑ library photo

- ↑ "PLAN APARTMENTS FOR 360 FAMILIES ON OLD RACETRACK: COOPERATIVE HOUSING FOR 360 FAMILIES PLAN APARTMENTS ON OLD RACETRACK." New York Times (1857-Current file), January 7, 1951, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 1, 2009), [hereafter NYT Plan].

- ↑ NYT Plan

- ↑ Ancestry.com - 1930 United States Federal Census. Available from http://content.ancestry.com/iexec/?htx=View&r=an&dbid=6224&iid=NYT626_1494-1082&fn=Wesley+A&ln=Roche&st=r&ssrc=&pid=39609915 (accessed 5/8/2009), [hereafter Ancestory Roche]

- ↑ NYT Plan

- ↑ Ancestory Roche

- ↑ U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Mortgage Insurance for Cooperative Housing: Section 213,” http://www.hud.gov/offices/hsg/mfh/progdesc/coop213.cfm.

- ↑ "Display Ad 966 -- No Title." New York Times (1857-Current file), January 7, 1951, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 1, 2009), [hereafter NYT AD].

- ↑ NYT AD

- ↑ GET LOAN OF $3,165,800: Builders Preparing to Erect Nostrand Gardens 'Co-op'." New York Times (1857-Current file), June 17, 1951, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 1, 2009).

- ↑ Gerald Sazama, 1996. "A Brief History of Affordable Housing Cooperatives in the United States,"Working papers 1996-09, University of Connecticut, Department of Economics. (accessed May 8, 2009).

- ↑ Richard Seigler, Eva Talel, 2006. “Noise and the Warranty of Habitability,” New York Law Journal, Vol. 235, No.40. (accessed May 26, 2009)