One of my most favorite things about this class is my recently developed knowledge of history’s art and my new ability to make connections between pieces across time periods. When I recently visited the Met, I found myself experiencing this very feature. On display in the European Sculpture and Decorative Arts exhibit is an exquisite oil-gilded statue of David titled David with the Head of Goliath. Sculpted out of bronze by Italian artist Bartolomeo Bellano in the 15th century, the sculpture immediately made me think of Donatello’s famously bronze David (1425-1429). I was pleased to learn that Bellano was indeed one of Donatello’s disciples. Looking at the two together it is evident that Donatello set the path for Bellano’s later sculpture.

Bellano's David, David with the Head of Goliath, (1470–80)

Donatello's David, David1425 -1429

But Donatello and Bellano are certainly not the only artists who have attempted to depict David. Michelangelo and Bernini, amongst others, created magnificent portrayals of the biblical figure. What is interesting to learn, though, is the effect of each artists’ respective time periods on their depictions. Looking into these artists’ history explains some very important aspects of their work.

Italy was flourishing in the 15th century. As the Italian Renaissance continued to shape the culture of Florence, much of the art produced was commissioned by the civil government, courts, and wealthy individuals, most notably the Medici family. Around 1430, Cosimo de’ Medici commissioned Donatello’s David. The first freestanding nude sculpture since classical antiquity, David is evidence of Donatello’s revival of ancient Greece and Rome’s love and respect for the body. The Middle Ages was a period when the focus was on G-d and the soul, so artists rarely represented the nude. David’s contrapposto position, originated by the ancient Greeks, gives the sculpture a sense of movement, unlike the stance of the traditional male figure. David’s right leg is pushed up, causing the wing of Goliath’s helmet to ride up his left thigh. The beginnings of Humanism are apparent, as Donatello forms David’s body with his pioneered shallow relief technique. Donatello’s choice of bronze, the nudity, and contrapposto pose emulate the Humanist antique.

Donatello’s novel young figure of David embodies the ideals and concerns of 15th century Italy. At about five feet tall, David symbolized the Republic of Florence. Donatello stressed David’s victory as a sole result of G-d’s influence; David’s youth, slender physique, boyish expression, and rock in his left hand portray the slaying of Goliath as a direct result of Divine Intervention. The Florentine people saw their success in defeating their enemy, the Duke of Milan, in the early 15th century as the hand of G-d. Florence was a mercantile republic, as opposed to Milan, which was a military power and autocracy. David became the symbol of the Florentine Republic and peace, while Goliath took on the role as the Duke of Milan.

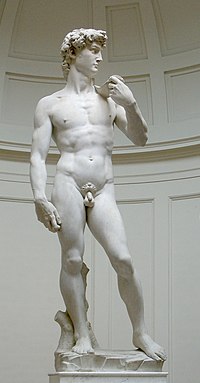

Michelangelo's David, David, 1504

At the height of Humanism in the High Renaissance, Michelangelo created his David. Michelangelo’s David differed from Donatello’s in its adolescent physique and absence of Goliath’s head. David’s marble face, tense and ready for combat, bulging veins in his right hand, yet contrapposto pose suggest that David is portrayed after he has made the decision to fight Goliath, yet before the battle has actually begun. David’s serenity of conscious choice prior to dangerous action is consistent with Renaissance ideals.

Michelangelo’s David embodies the fully developed Renaissance idea that man is G-d like because he is created in G-d’s image. David’s perfectly chiseled tendons and uninterrupted contour depict strength and wrath, Florence’s two most important virtues, as it had just cast the ruling of the Medici family. The Florentine people immediately identified with the colossal David as a shrewd hero over superior enemies.

Bernini's David, David, 1623-1624

There is no time for contemplation in Bernini’s David. Actively fighting Goliath, this David challenges the conventions of time and space. Michelangelo and Donatello’s Davids are serene and pensive; Bernini captures David in his moment of action. The path to G-d during the Renaissance was through the mind; Michelangelo and Donatello’s Davids ask the viewer the contemplate the beauty of man, G-d’s greatest creation, which will lead the viewer to an understanding of G-d. However, in the Baroque era, the path to G-d was more direct, emotional, and bodily. Baroque art dares its viewers to relate to the image in our bodies, not just our minds. Bernini’s David is actively involved in its surrounding space. The viewer must walk around it on all sides to experience its full effect. David’s toes literally step of the plinth. The contour of his body is crossed by his twisting cloth, the line of his neck, his bending arm, and the sling across his chest, heightening the spiraling of his body. Bernini forms David like a wound spring, while paying attention to the realism of the body. The visual tension creates deep shadows and intense illumination, typical of Baroque style.

Nowadays, we tend to think that art is only good if it is new and innovative. But these artists attest to the timeless artistic practice of learning from others and perfecting their work.

Thanksgiving is over, and we in Professor Smaldone’s seminar enter our final stretch of our first semester in college (Crazy, huh?). But the closing of November marks the termination of another event- NaNoWriMo! No, this is not a Japanese sitcom. This is National Novel Writing Month, a unique, stimulating challenge for creative writers around the world. The task: to write a 50,000 word (or more) novel in one month. No previous experience in the art of writing is necessary. In fact, NaNoWriMo was created in 1999 by 21 non-writers who decided to embark on a monthlong journey just to get their voice out there. They wanted to write novels not out of any aspirations of tapping into their creative selves, but rather for the same reason angry teenagers start doomed-for-failure boy bands- to make some noise. And, they claim, “Because we thought that, as novelists, we would have an easier time getting dates than we did as non-novelists.”

Thanksgiving is over, and we in Professor Smaldone’s seminar enter our final stretch of our first semester in college (Crazy, huh?). But the closing of November marks the termination of another event- NaNoWriMo! No, this is not a Japanese sitcom. This is National Novel Writing Month, a unique, stimulating challenge for creative writers around the world. The task: to write a 50,000 word (or more) novel in one month. No previous experience in the art of writing is necessary. In fact, NaNoWriMo was created in 1999 by 21 non-writers who decided to embark on a monthlong journey just to get their voice out there. They wanted to write novels not out of any aspirations of tapping into their creative selves, but rather for the same reason angry teenagers start doomed-for-failure boy bands- to make some noise. And, they claim, “Because we thought that, as novelists, we would have an easier time getting dates than we did as non-novelists.”

If you watched Steven McRae tap away at the Fall for Dance Festival at City Center and thought, “Wow! I wish I could do that!” then I have some exciting news for you. The American Tap Dance Foundation is offering tap dance classes specifically geared towards children and teens. The classes run through June 2012. All levels are welcome and you can drop in and try an adult class for only $15. The foundation aims to teach America’s youth this indigenous art form. Founded in 1986 by master tap dancers Brenda Bufalino, Tony Waag, and the late Charles “Honi” Coles, the ATDF has performed in hundreds of concert, stage and film projects around the world, captivating its audiences. The ATDF is a nonprofit organization which provides “year-round programming of performances, workshops, daily classes for adults and children, tap jams, lectures and film presentations.” Now under the direction of Tony Waag, the ATDF has fulfilled its dream of creating an international tap center in New York City. The organization’s sole mission is its commitment to “establishing and legitimizing Tap Dance as a vital component of American Dance through creation, presentation, education and preservation.” How’s that for interactive art!

If you watched Steven McRae tap away at the Fall for Dance Festival at City Center and thought, “Wow! I wish I could do that!” then I have some exciting news for you. The American Tap Dance Foundation is offering tap dance classes specifically geared towards children and teens. The classes run through June 2012. All levels are welcome and you can drop in and try an adult class for only $15. The foundation aims to teach America’s youth this indigenous art form. Founded in 1986 by master tap dancers Brenda Bufalino, Tony Waag, and the late Charles “Honi” Coles, the ATDF has performed in hundreds of concert, stage and film projects around the world, captivating its audiences. The ATDF is a nonprofit organization which provides “year-round programming of performances, workshops, daily classes for adults and children, tap jams, lectures and film presentations.” Now under the direction of Tony Waag, the ATDF has fulfilled its dream of creating an international tap center in New York City. The organization’s sole mission is its commitment to “establishing and legitimizing Tap Dance as a vital component of American Dance through creation, presentation, education and preservation.” How’s that for interactive art!

One of my favorite things about New York City is its surprises. Every street corner you turn holds potential for a new discovery. On the corner of West 36th and 10th Avenue, the unfamiliar Exit Art cultural center strives to present “innovative exhibitions, films and performances that reflect a commitment to contemporary issues and ideas.” Since 1982, Exit Art has housed exhibits that are anything but the usual.

One of my favorite things about New York City is its surprises. Every street corner you turn holds potential for a new discovery. On the corner of West 36th and 10th Avenue, the unfamiliar Exit Art cultural center strives to present “innovative exhibitions, films and performances that reflect a commitment to contemporary issues and ideas.” Since 1982, Exit Art has housed exhibits that are anything but the usual. My father is an indie film connoisseur. If you have ever looked at the cover of an offbeat, home videoed movie and thought, “What the…?” you can be sure he has watched it. His flick taste is how I came across the incredible story of Herb and Dorothy Vogel. Possessing a seven million dollar art collection, Mr. and Mrs. Vogel live in a modest one-bedroom apartment in New York City. Herbert, 89-years-old and the son of a Russian garment worker from Harlem, never completed high school and worked as a clerk for the United States Postal Service until he retired in 1980. 76-year-old Dorothy, daughter of a New York stationary merchant, obtained a masters degree and worked as a librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library. So how did these two seemingly unassuming individuals amass a multimillion-dollar art collection?

My father is an indie film connoisseur. If you have ever looked at the cover of an offbeat, home videoed movie and thought, “What the…?” you can be sure he has watched it. His flick taste is how I came across the incredible story of Herb and Dorothy Vogel. Possessing a seven million dollar art collection, Mr. and Mrs. Vogel live in a modest one-bedroom apartment in New York City. Herbert, 89-years-old and the son of a Russian garment worker from Harlem, never completed high school and worked as a clerk for the United States Postal Service until he retired in 1980. 76-year-old Dorothy, daughter of a New York stationary merchant, obtained a masters degree and worked as a librarian at the Brooklyn Public Library. So how did these two seemingly unassuming individuals amass a multimillion-dollar art collection? Tap-dancing dates back to the 1650s when Oliver Cromwell “shipped an estimated 40,000 Celtic Irish soldiers to Spain, France, Poland, and Italy.” Soon after, thousands of Irish men, women, and children were kidnapped and deported to the expanding English colonies to work the tobacco plantations. The Irish brought with them their famous Irish jig and style of step dancing.

Tap-dancing dates back to the 1650s when Oliver Cromwell “shipped an estimated 40,000 Celtic Irish soldiers to Spain, France, Poland, and Italy.” Soon after, thousands of Irish men, women, and children were kidnapped and deported to the expanding English colonies to work the tobacco plantations. The Irish brought with them their famous Irish jig and style of step dancing.