From The Peopling of New York City

A Glimpse

please click below to directly enter the Five Pointz page

New York's Post-Modern Five Pointz: The Secret History of Aerosol Art

7 train (Express or Local) to 45th Road/ Court House Square

Five Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin' at 22-42 Jackson Avenue

Five Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin' at 22-42 Jackson Avenue

CEO of Five Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin'

please click the link below for:

1. more pictures and videos of Five Pointz

2. information on the researcher: Catherine Chan

Biography & Multimedia

A Walking Tour of Five Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin'

IMPORTANT: be sure to watch this virtual walking tour as it corresponds to the narrative below

Let’s take a ride on the 7 train: express or local? It’s your choice. As the train shimmies along the steel tracks between Queensboro Plaza and 45th Road- Court House Square, you notice a collage of magnificent views, but perhaps the most unique is not the 59th Street Bridge, but rather a simple warehouse embellished in what we would colloquially call “graffiti.” This is Five Pointz, a warehouse dedicated to the practice of aerosol art. It is delineated by Davis Street, which runs under the 7 train, Jackson Avenue, and Crane Street. Almost ironically, P.S. 1, New York City’s first public school is located just across Jackson Avenue on 46th Avenue. Depart the 7 train at 45th Road- Court House Square. Walk along Jackson Avenue until you have reached Crane St. Do a 360o; take it all in, making a panorama from the images your eyes have captured. Zoom into 5 Pointz.

You are standing in the midst of a dichotomy, a juxtaposition of the arts. On your right is Five Pointz, and to your left, across the street is a concrete block engraved with the symbols, P.S. 1. You take a glance at P.S. 1, but you stare at 5 Pointz. There is something less rigid about its walls, perhaps it’s the art that adorns them that makes the old warehouse a little bit more welcoming and a little less institutionalized.

From Jackson Avenue you make a right onto Davis Street. Walking along Davis Street, you notice a mural just before the “loading dock” or the entrance. It is of a man who faintly resembles Arnold Schwarzenegger in the “Terminator.” As the audience, you feel like the target of the two guns in his hands. The revolver in his left hand is slightly tilted and radiates a mysterious aura, while the gun in his right hand points at you dead on. The sparks of light gleaning at the rims of his sunglasses seem to reflect the explosions occurring around him. Mesmerized by this scene, you continue to walk, your eyes always watching the barrels of his guns. And then it hits you. The piece is fashioned so that, at any angle, it the man always seems to be shooting at you. It is as if he moves, as you move; and the threat of the gun never ceases. Let’s continue and enter the loading dock.

Underneath the Paint: The Origins of Modern Graffiti

Modern graffiti did not originate in New York City, but rather in Philadelphia where two African American youths named Cornbread and Cool Earl scribbled their names all over the city. Although it is important to note that the art form originated in Philadelphia, it is safe to say that the Big Apple is where modern graffiti thrived. The practice of graffiti spread to New York City in the late 1960s, thriving in areas such as Washington Heights, Brooklyn and the Bronx. By the mid- 1970s, this modern art form “plagued” the New York City Subway system, so much so that “it was impossible to see out the window”.[2]

The painting of the subways emerged as a response to specific historical events occurring in New York during the late 1960s and the early 1970s. Youths, especially those of color, protested such events as the Vietnam War, racism, and poverty. “The writer’s actions followed this strategy by bombing (a technique of painting trains) a subway system that to many represented an uncaring bureaucratic system”. Yet perhaps the most significant war was the war against racism.[3]

"Living on the Wrong Side of the Tracks": African-American Roots of Graffiti

"The term graffiti is a racist, denigrating term that was applied to our culture, a culture invented by the children of the working class, usually people of color: Black and Puerto Rican, Black and Latinos…not a culture invented by the children of the rich upper classes, because if it were, the media would never have denigrated the new art form with the term ‘graffiti.’ They would have named it a ‘vanguard pop-art’ something". –MICO [4]

Today, modern graffiti, or should I say aerosol art, is evidently a multi-cultural and worldwide phenomenon. It is now a practice that encompasses a spectrum of peoples from different races, ethnicities, and social standings. However, there are remnants of the struggles that characterized the "hard knock life" of the working class in New York City that can still be found in aerosol art to this day. More specifically, emphasis placed on themes such as establishing a name for oneself, as well as, the juxtaposition of vibrant hues in a ‘rhythmic framework’ trace the birth of modern graffiti back to the African American experience.

Throughout history, African Americans and immigrants alike have found themselves “living on the wrong side of the tracks”. Living under poor economic conditions, as well as the glass ceiling of race, the children of the working class rarely enjoyed the privileges that their white counterparts easily obtained. Graffiti, as a result, was a way for these youths, these people of color, to not only transgress beyond the barriers of race, but also to establish an identity for oneself in the larger framework of society; it is a matter of making yourself known. As Cool Earl, one of the pioneers for modern graffiti, once said “You go somewhere and get your name up there and people know you were there”. [5] Graffiti was a method of protesting assimilation. It is the creation of a distinct culture that blends the traditions of their nationality with their own individual experiences. This new culture of aerosol art serves as weapon in the “larger struggle for social justice.”

Similar to the African American struggle against racism are the experiences of all people of color. A majority of early writers are African or Caribbean youths who lived in ghettos and are as mentioned, the children of the working class. Thus, it seems that aerosol art has brought together peoples of different races to form a collective movement in the struggle against racism and assimilation.

The War on Graffiti: The White-washing of Immigrant Culture in New York City

Graffiti has been consistently deemed an urban blight throughout the history of New York City. As a result, it has always been a goal of the Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) as well as, the NYC government to cleanse the city of this form of vandalism. Yet, was it the underlying motive of this cleansing to force assimilation upon immigrants by eliminating their expression of self? Was this a conscious racist attempt to silence the work that revealed the reality of living in New York City?

There seems to be a trend, throughout history, that people who wanted to eradicate graffiti were also white. These people include Mayor John V. Lindsay and Mayor Rudolf Giuliani.

Mayor John V. Lindsay

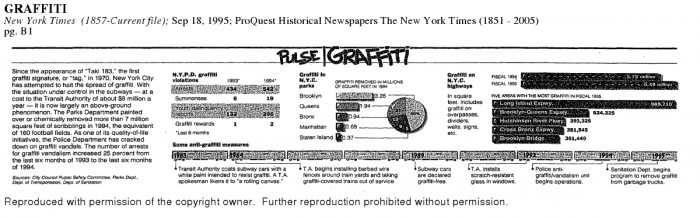

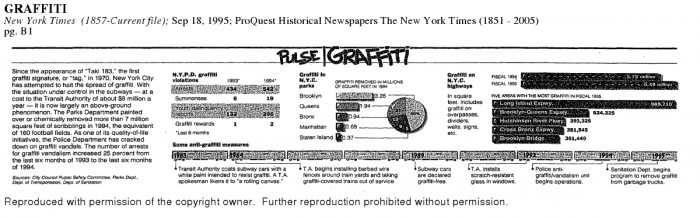

A Timeline of Graffiti Decline in New York City

In the early 1970’s, a plethora of graffiti descended upon the subway cars and stations of New York City. Transit authorities deemed these pieces of work as acts of vandalism causing the issue to enter the political realm. In fact, the first war on graffiti began in 1970 with Mayor of New York City, John V. Lindsay. Pressured by officials, as well as, his WASP counterparts, Lindsay was inclined to cleanse the city of this ‘vandalism.’ By 1973, the cost for the removal of graffiti was $10 million per year, not to mention that graffiti continued to thrive. [8]

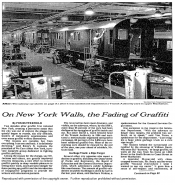

As illustrated by the timeline above, the Transit Authority began to use a graffiti-resistant paint in 1983. More commonly called “graffiti-resistant white,” graffiti masterpieces were painted over with this ghostly hue to prevent graffiti from resurfacing. Thus, the literal and metaphorical whitewashing of immigrant cultures began. However, this white paint was not as resistant as transit officials had hoped. As a result, a new technology of resistant paint was developed, this time it was clear and offered graffiti artists the illusion that such subway cars could be written upon. This false sense of hope is also a method used by the white upper class of the Upper East Side to force assimilation upon their colored tempest-tossed, less affluent counterparts living in the slums and the ghettos of New York City. On May 12, 1989, the war on graffiti was over, declaring a victory for Mayor Lindsay, the Transit Authority, and ultimately, the affluent whites. This “international symbol of decay and crime was completely eradicated from the system, but not the perception of it.” [9] Little did they know, that graffiti would once again resurface not only as retaliation against racism and integration, but also as a more accepted and appreciated art form.

an aerosol artist posing as he prepares to paint the train

|

graffiti on NYC subway cars

|

|

|

Mayor Rudy Giuliani

Graffiti Arrests in 1998 Fiscal Report

Increase in Vandalism Arrests up to 2001[11]

The second and ongoing war on graffiti was declared on July 11, 1995 by Mayor Rudolph Giuliani. In his Executive Order No. 24, Giuliani formally established the Mayor’s Anti-Graffiti Task Force in an effort to improve the quality of life in New York City.[12] Yet, is beautifying the city the real driving force behind this initiative, or is it another reason to mask the realities of life that are reflected in graffiti?

Graffiti Free NYC: Anti-Graffiti Unit

Graffiti Concealer: White Paint[13]

Giuliani’s task force works in conjunction with NYPD’s Anti-Graffiti/ Vandalism Unit to ensure that these artists are caught and prosecuted for the crime of vandalism. In 1995, 258 arrests were made for vandalism; in 1996, 333 arrests were made; in 1997, 317 and finally in 1998, 375 arrests were made. Although this chart may illustrate the NYPD’s increased diligence in catching vandals, it also shows retaliation on the side of the artists. We can determine that the spike in arrests made between the years 1996 and 1998 meant that more and more graffiti artists were coming out. They were compelled to voice their disgust with the Mayor’s initiative through aerosol art even at the risk of arrest.

The city, under the white gloves of Rudy Giuliani, was once again trying to silence the immigrant experience reflected in graffiti, but this time artists rebelled in larger numbers and with greater intensity; thus, making this an ongoing and ever present struggle.

Today, the Mayor’s initiative is presented under a catchier alias- “Graffiti Free NYC.” This includes the Mayor’s Paint Program which is administered by the Mayor’s Community Affair’s Unit (CAU). The paint program provides supplies, such as paint and rollers, for fellow New Yorkers who want to remove graffiti on their own instead of consulting the Anti-Graffiti Unit. In either option, walls adorned with graffiti are painted over with white paint.[14] s a result, we once again witness a whitewashing of the immigrant experience. Assimilation is being forced upon the artists, while their experience, their reality is being silenced

A Continuing Struggle: Five Pointz- The Institute of Higher Burnin'

Eavesdropping on History: How it came to be Five Pointz

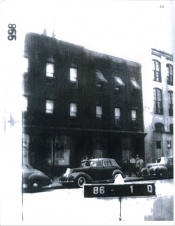

1940 Tax Photo of warehouse currently known as Five Pointz[15]

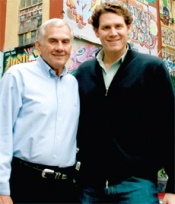

Jerry Wolkoff (left) and his son Five Pointz is full of contradictions, with the most obvious one being its location. The building itself possesses two addresses: 22-42 Jackson Avenue and 45-46 Davis Street. If you were to continue walking along Davis Street, under the 7 line, you would hit the rails of Amtrak and the Long Island Railroad- it’s a dead end. Here we are in the courtyard of the castle that is 5 Points: The Institute of Higher Burnin’. What secrets are not manifested through the graffiti, the murals, or spray paint?

Five Pointz, constructed in 1900, is a five-story, 200,000 square-foot warehouse currently owned by Gerard Wolkoff also known as Jerry. [17] In fact, it seems that Mr. Wolkoff, president of Heartland Business Center, and his family has owned this building since June 11, 1971 for approximately thirty-seven years.[18] According to the New York City Department of Finance, the lot has been listed as an irrevocable trust since January 7th, 2000, meaning that the trust remains in effect and cannot be changed without consent of the beneficiary. [19]The grantor, who in this case is the Wolkoff family, transfers his asset, which is the lot, to such a trust and essentially relinquishes his control of the asset. Generally, business owners establish an irrevocable trust for charitable reasons, to give back to the community.

How does a developer like Jerry Wolkoff decide to postpone his development plans, and dedicate a very promising lot to aerosol art? “I have a certain passion for people in the art business,” says Jerry, “I have no problem as long as they do it tastefully and don’t endanger themselves”. [20] Mr. Wolkoff’s son, David Wolkoff further adds, “We like to give back to the community, and this is one way to do it”. In fact, a majority of the building’s interior has been converted into 90 artist’s studios called “Crane Street Studios.” There are sculptors, painters, and other visual artists, many of who have achieved recognition for their work. [21]The other twenty percent of space is dedicated to light manufacturing in the garment industry. Therefore, this warehouse seems to subconsciously be a manifestation of America’s first slum, Five Points which was a bringing together of different peoples on the basis of economic status and race. Five Pointz: The Institute of Higher Burnin’ symbolizes a coming together of not only artists and businessmen, but also of aerosol art and society’s norms. After all, this warehouse is the only place where graffiti is legal throughout the five boroughs of New York City. As a result, it is a place where something traditionally seen as an urban blight is celebrated as an actual art form.

The warehouse was not always known as Five Pointz. In fact, the aerosol art program began in 1993 with Pat DiLillo. The forty-year-old retired plumber established, with the aid of Mr. Wolkoff, the Phun Phactory. Ironically, this program evolved from “Graffiti Terminators” which was also formed by Mr. DiLillo. Graffiti Terminators, as its name suggests, was a group aimed to combat the spread of graffiti by repainting walls that were affected. [22] However, instead of constantly combating the artists, Mr. DiLillo created for them, a haven where they can proudly produce and showcase their work. The subway trains are no longer their medium of choice, but rather their true canvas is the warehouse. Although it is still illegal in New York City, the creation of this program has transformed the eyesore known as graffiti into an appreciated and legitimate form of art- aerosol art.

Jonathan Cohen, also known as Meres One, “took over the program in 2002 after Pat DiLillo moved to Pennsylvania. Cohen, who is certified by the Board of Education, offers classes, cultivates his own career as an artist and curates the offerings at the Wolkoff building, which he dubbed Five Pointz after the city’s five boroughs”.[23]Mr. Cohen, who will now be referred to as Meres, offers classes to young promising aerosol writers on Sundays. In return, the students help him paint over certain works so as to prepare the wall for a new mural in its place. Meres, “whose dream is to have the building “100 percent covered,” supports the program with the help of donations and his volunteers and fellow artists. [24] Consequently, as the CEO, Meres decides which pieces are produced and where. Currently, “the future of 5 Pointz is undetermined, but [the] goal [of the artists] is to one day establish a museum in this location based on [aerosol art] and the artists that have been impacting this culture since the 1970's”. [25] Aerosol art has always been viewed as an urban blight. However, through the formation of these programs, and the transformation of the Wolkoff warehouse, graffiti or rather aerosol art has become a more accepted and a more sought out art form. “Everyday, another writer is born”.[26]

Five Pointz: Is it really a safe haven for aerosol artists?

a flyer distributed by the NYPD: Graffiti Awareness for Parents As the only place in all of New York City where graffiti is not considered a crime, Five Pointz proves to be a haven for aerosol artists. Today, artists from all over the world come to this warehouse to produce their work, to essentially tell their story. As LADY PINK says, “Graffiti writers include people from all ages, all creeds, genders and sizes. This would be a strong point to mention.” (1) Although the graffiti artists of today include people from a palate of races, social standings, and ethnicities, does a hint of whitewashing still linger? Is Five Pointz a true refuge for the practice of aerosol art, and in that case, does it protect the writers and their stories; or does the struggle continue?

Let’s run over the facts. Five Pointz is now curated by Jonathan Cohen also known as Meres One. Under the title, Phun Phactory, the graffiti program was run by Pat DiLillo. Overall, the landlord and owner of this lot is Gerard also known as Jerry Wolkoff. These are the three important figures that oversee the maintenance of Five Pointz, and they are all white. Although there is a plethora of white aerosol artists including Meres, the warehouse is not a true haven for the immigrant experience, but rather it reflects the continuous struggle against racism and assimilation.

As mentioned, Meres, as the curator and CEO of Five Pointz, determines how long a piece remains on the walls of the warehouse, which ones are painted over, and which ones remain. Ultimately, he controls which stories are whitewashed so that others can be told. This is a leap from the 1970’s when the immigrant experience, their struggles and their realities were simply silenced and never retold. In the case of Five Pointz, each artist has a chance to tell his or her story. The only catch is that Meres, an aerosol artist himself, serves as the final judging factor.

Jerry Wolkoff, as the landlord, also proves to be a powerful character in the story of graffiti. In April 2009, an external staircase collapsed at Five Pointz injuring Nicole Gagne, a jewelry artist who worked in the factory converted studios of the warehouse. She was “trapped under 20 feet of cement and debris” and was sent immediately to Bellevue Hospital on Saturday, April 11th. A “preliminary investigation revealed the collapse was caused by neglect and failure to maintain the building”. As reported by the New York Daily News,

"The Buildings Department cited the owner, G&M Realty, five times last year for illegally converting the factory to artist studios, records show. G&M Realty, of Edgewood, N.Y., is owned by developer Gerald Wolkoff and his family. They couldn't be reached Saturday."[27]

Jerry Wolkoff is responsible for the maintenance of this graffiti haven. However, it seems that the warehouse has been deteriorating due to neglect. His neglect for the lot converts into neglect for the stories of the artists whose masterpieces adorn the building. The literal collapse of Five Pointz proves that the struggle against assimilation and racism is a very present one. Whitewashing still continues with the Mayor’s Anti-Graffiti/ Vandalism Unit. In addition, the only refuge for the immigrant experience is breaking apart. Let’s hope that Five Pointz, under the leadership of Meres the aerosol artist, can achieve its museum status so that its art can stand just as proudly and be appreciated like its P.S. 1 counterparts across the street.

References

- ↑ Sarah Bayliss, Museum With (Only) Walls," New York Times, (August 8, 2004), http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/08/arts/art-architecture-museum-with-only-walls.html?scp=1&sq=museum%20with%20only%20walls&st=cse (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ Dimitri Ehrlich and Gregor Ehrlich, “Graffiti in Its Own Words,” New York Magazine (June 25, 2006) http://nymag.com/guides/summer/17406/ (accessed April 30, 2009)

- ↑ Ivor L. Miller, Aerosol Kingdom (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi , 2002), 15

- ↑ Hugo Martinez, Graffiti NYC (New York: Prestel, 2006), 54

- ↑ Ernest L. Abel and Barbara E. Buckley, The Handwriting on the Wall (London: Greenwood Press, 1977), 140

- ↑ GRAFFITI. 1995. New York Times (1857-Current file), September 18, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 28, 2009). document URL: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=115867655&Fmt=10&clientId=4273&RQT=309&VName=HNP

- ↑ FOX BUTTERFIELD. 1988. On New York Walls, the Fading of Graffiti :On New York's Walls and Trains, the Fading of Graffiti. New York Times (1857-Current file), May 6, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 28, 2009).

- ↑ Murray Shumach, “Lindsay, Decrying ‘Vandalism’ Reports $24-Million a Year Would be Needed to Reduce Defacement Appreciably,” New York Times (March 28, 1973) http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40D14FC3F5C147A93CAAB1788D85F478785F9&scp=1&sq=%20at%20%2410million,%20city%20calls%20it%20a%20losing%20graffiti%20fight&st=cse (accessed May 1, 2009)

- ↑ Mark S. Feinman, “The New York Transit Authority in the 1980s,” (Dec 8, 2004) http://www.nycsubway.org/articles/history-nycta1980s.html (accessed May 1, 2009)

- ↑ Martinez 2006

- ↑ ”Combating Graffiti: Reclaiming the Public Spaces of New York” 2009 http://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/html/crime_prevention/anti_graffiti_initiatives.shtml (accessed May 5, 2009)

- ↑ “Summary Volume of the Fiscal 1998 Mayor’s Management Report” http://www.nyc.gov/html/cau/html/qol/anti_graffiti.shtml (accessed May 5, 2009)

- ↑ http://www.nyc.gov/html/cau/html/qol/anti_graffiti.shtml

- ↑ ”Quality of Life: Graffiti Free NYC” 2009 http://www.nyc.gov/html/cau/html/qol/anti_graffiti_paint_program.shtml (accessed May 5, 2009)

- ↑ NYC Municipal Archives. Queens Tax Photos: NYC/DORIS Queens c1940 file #298 (on microfilm)

- ↑ Chang W. Lee/The New York Times. 2002. Photo Standalone 1 -- No Title. New York Times (1857-Current file), May 29, http://www.proquest.com/ (accessed April 28, 2009). Document URL: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=727109482&Fmt=10&clientId=4273&RQT=309&VName=HNP

- ↑ Marc Ferris, “Graffiti Now, Condos Later in LIC,” New York Times, (April 29, 2008), http://ny.therealdeal.com/articles/graffiti-now-condos-later-in-lic (accessed April 1, 2009): 1-2

- ↑ David Gonzalez, “Legal Graffiti? The Police Voice Dissent.” New York Times (September 11, 1996), http://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/11/nyregion/legal-graffiti-the-police-voice-dissent.html?scp=2&sq=phun%20phactory&st=cse (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ New York City Department of Finance: Office of the City Register, http://a836-acris.nyc.gov/Scripts/DocSearch.dll/BBLResult?max_rows=99 (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ Sarah Bayliss, “Museum With (Only) Walls,” New York Times, (August 8, 2004) http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/08/arts/design/08BAYL.html?scp=3&sq=5%20pointz&st=cse (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ Marc Ferris, 1-2

- ↑ Richard Wier, “Neighborhood Report: Long Island City; Wall Hits a Patron of Graffiti,” New York Times, (February 15, 1998), http://www.nytimes.com/1998/02/15/nyregion/neighborhood-report-long-island-city-wall-hits-a-patron-of-graffiti.html?sec=&spon= (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ Marc Ferris, 2

- ↑ Sarah Bayliss, 1

- ↑ “5 Pointz,” http://www.5ptz.com/ (accessed April 1, 2009)

- ↑ David Gonzalez, 2

- ↑ Tina Moore and Mike Jaccarino, “Landlord’s ‘neglect’ nearly killed artist,” Daily News (April 12, 2009) http://www.nydailynews.com/ny_local/queens/2009/04/12/2009-04-12_landlords_neglect_nearly_killed_artist.html (accessed May 10, 2009)

Link title