Brooklyn College: The Early YearsFrom The Peopling of New York CityBrooklyn College's motto is "Nil sine magno labore," or "Nothing without great effort." How apropos for a college whose beginnings were so driven by the efforts of its faculty and students. For its first seven years, Brooklyn College was a much-needed, packed college situated in five buildings in downtown New York. Perhaps not the most auspicious of beginnings, but the people of Brooklyn College were determined to make it work. And work it would right up until now, as I work on a wiki for a class in Brooklyn College, now a respected city college on a beautiful campus. "The Portals of Joralemon" were a far cry from "A former field in Flatbush, now a campus lush and green," but they were the start of it all, and those formulative years are what fascinated me from the start. I intended to do this project on Hillel Place, just outside the current Brooklyn College. Without any information from pertinent sources, I took out a book from the library entitled Brooklyn College: The First Half-Century. I meant to skim it for references to Hillel Place, but instead, I found myself intrigued by the first chapter, where Murray M. Horowitz details the lives of the early students and faculty of Brooklyn College. And suddenly, my project was transformed from a necessary evil to a journey back to a time where the everyday lives of the inhabitants of Court, Willoughby, and the others were as real to me as my own on Campus Rd. Here it is, laid out for you- Welcome to the newly established Brooklyn College.

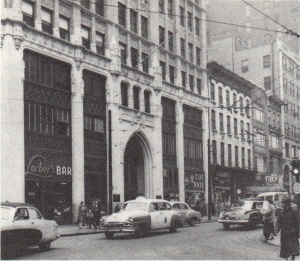

FormationThe Board of Higher Education authorized Brooklyn College on April 22, 1930. It was a city college, thus with free tuition, and was situated in four (later five) buildings in downtown Brooklyn. The College was coeducational, sharing all-male City College’s curriculum and degree requirements for men and all-female Hunter College’s curriculum and degree requirements for women. In fall of 1931, classes were segregated until junior year, when financial constraints forced electives to be open to both men and women. Plans were made to, in time, segregate those as well. How could a college with free tuition limit the number of students flooding in? No applications with detailed background information were required by the college. Instead, students were accepted if they had adequate high school grades, and received a penny postcard notice of admission. The merger of City-Hunter College that had been established in Brooklyn in 1926 boasted 623 men and 308 women. On the first day of class at Brooklyn College, Thursday, September 18, 1930, these numbers tripled and quadrupled. 2,676 daytime students and 2,583 nighttime ones seemed to guarantee that “there is little doubt of the immediate and complete success of the local institution.” [1] LocationsIn gentle springtime, when traffic lights are green [2]

View BC in a larger map

There was no space for teachers' offices or club rooms. Instead, students and faculty had to make do with what they had. Faculty members would meet with students in the rooms assigned to them, and time was set aside every Wednesday for clubs to meet in the classrooms. Without sports facilities, the only athletic clubs were the gymnasts and the wrestlers, and there was a greater emphasis on literary clubs. [4] The theater department was also very active. Its beginnings were humble, a small platform in one of the classrooms, but as the theater troupe grew, local theaters were rented out for entertainment. [5] The Star Burlesque Theater, located behind the Lawrence Street building, was an unforgettable part of early Brooklyn College. Between shows, performers caught the attention of students sitting in the favored window seats in trigonometry class. Some students would even arrive early, "the better to learn about angles and curves." [6] Others skipped classes to go see performances there and in the other theaters and cinemas that surrounded them in downtown Brooklyn. Leon Labes recalls skipping a Shakespeare class "because there was a certain stripper that I was very anxious to see at the Star Burlesque and I told [the Professor] I wasn't quite sure whether I had gone from the sublime to the ridiculous or from the ridiculous to the sublime." [7] School LifeIn the era following the Great Depression, when "people were selling apples on the street" [8], students and faculty alike had to pinch pennies to manage. Despite its free tuition, school still cost money. Carfare to and from school for one student was five cents each way, or fifty cents a week.[9] Lunch had to be brought from home for most, because the average lunch in college was 15 cents, according to the Curator's Report. [10] The average student's college-related expenses were about $6.60 a week in 1934. The faculty also felt the toll of the economic situation. In 1930, the faculty had to "volunteer" one percent of their wages to the unemployment fund. Two years later, an emergency pay cut was levied on all city employees, and tiny salaries grew even smaller. Many cheap restaurants in the area were patronized by students and faculty alike during the day. [11] In a school as small as the young Brooklyn College, students and faculty alike were a close-knit crew. One student speaks of an English teacher who would have him for dinner and encourage him to use his writing talents. [12] Another recalls his wife going out to tea with her professors, and he going with a few students and faculty members to Washington on a trip. [13] The president of the college, Dr. William A. Boylan, was seen as an austere, remote figure to the students. Faculty members describe him as reserved and respectful to them, always trying not to interfere and quick to accommodate. [14] School NewspapersIn its first few years, three newspapers kept daytime students informed. The first, the Brooklyn College Pioneer, by men and aimed at men; and the second, the Brooklyn College Spotlight, the female version; merged in 1935 to become the Brooklyn College Vanguard, with editors-in-chief formerly from both papers. The first editorial on February 28, 1936 carried the headline “We Take Our Stand” and stated: “We are not discarding the liberal traditions of either of the former newspapers—traditions based on faithfulness, dependability and honesty…We shall be faithful to the student body by publishing a newspaper which is representative of their interests…We shall necessarily ally ourselves with those youth organizations which are progressive in their principles, for Brooklyn College students have shown that they realize the necessity of working for the establishment of peace, the maintenance of academic and civil freedom and adequate educational facilities for all….We shall be honest in facing present conditions, honest and analyzing their solutions…If we succeed in making ourselves felt as a vital force in the College, not only in reporting activities, but in directing and guiding them, we feel that we shall successfully perform our function as the Brooklyn College newspaper.” [15] Controversy arose in 1935 when Eli Jaffe, a political radical, was rejected from the job of editor-in-chief of the Pioneer because of his political views, the votes of two student members of the Pioneer Association overridden by three faculty members. The newspaper staff went on strike, demanding that he be instated in the position. The Spotlight was quick to back up their decision, as did various other school papers and literary publications. [16] This was just one example of the many anti-authority statements Brooklyn College students became known for in the 1930's.Articles from the Pioneer Board, a two-page issue devoted to publicizing the strike: Alma MaterWhen a competition was announced to determine the alma mater for Brooklyn College, poet Robert Friend wrote a scathing parody of the genre that, to his chagrin, won the contest. [17] Sylvia Fine Kaye, then a student at Brooklyn College, wrote her own song, but the head of the music department, with whom she didn't quite get along, rejected her words in favor of Friend's and kept the music [18]. Media:BCAM.mp3 No one was pleased with this arrangement. Without her lyrics, Kaye greatly disliked the alma mater, and even a later Brooklyn College president, Dr. Robert Hess, found the song to be "truly unsingable" and pretentious. Hess eventually tracked Friend down at a college reunion. Friend's reaction was "I don't even want to think of it. I'm embarrassed by it. I'm sorry I wrote it." He told Hess to have Kaye rewrite the alma mater into the one we use today. [19] ConflictMany college students search for a cause to stand for, and thirties Brooklyn College students were no exception. As they looked to the future in their Great Depression world, they grew dissatisfied with what might (or might not) lie ahead. And trapped between World War I and the stirrings of World War II, students found a cause in opposing war altogether. In 1933, a poll done by the Beacon, a Brooklyn College evening session newspaper, indicated that sixty percent of its readership would rather suffer imprisonment than bear arms. [20] And one day in the spring of 1934, a walk-out strike was arranged during third-period classes, to last until fourth period began. After the success of this first strike, many followed, and more and more students supported the antiwar protests,sometimes as many as five thousand students. [21] They were careful to keep the protests low-key and peaceful, determined not to turn the protest into an attack on the college. They were later commended by the Brooklyn Eagle because their protest meetings were "characterized by order and quiet," and college officials found that "its students are governed by healthy and wholesome attitudes." These protests continued well into the campus years of Brooklyn College, dying down in the the late 1930's. [22] Communism, while a major concern in some parts of the United States, in Brooklyn College, "there was a small, very small radical element but it was an extremely small minority, totally unvociferous." [23] But the Communists did latch onto issues that concerned most of the student body, like the threat of tuition in the city colleges, and therefore had some minor success in reaching people. [24]

ConclusionIt's been almost eighty years since Brooklyn College first became a reality. We've exchanged pencils with keyboards, carfare with Metrocards, and Ascutney with Boylan. And yet, we are inherently still the same school, with the same guiding principles that led us in the thirties. We're in an economic downturn again, and we're forced to make similar decisions to the students of yesteryear. Just a month ago, we followed in the Brooklyn tradition of activism and staged a walkout to protest tuition hikes. The future of Brooklyn College is still unknown, but if history does repeat itself, then looking to our past students as indicators of what should or should not be done is the key to our continued success. Notes

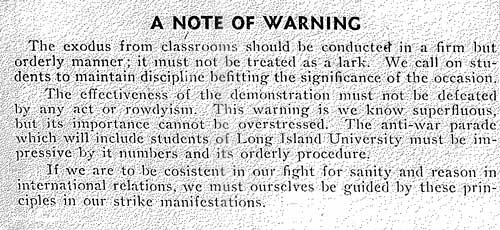

|