In June of 2014, police officer Daniel Pantaleo murdered 43-year-old Eric Garner with a chokehold. Garner died over allegedly selling untaxed cigarettes, a trivial crime. The real tragedy here is not Garner’s, death, though heartbreaking and avoidable; it lies in the fact that Pantaleo was in his full legal bounds to do what he did. In fact, Pantaleo was later acquitted because he did nothing legally wrong. We have to take a long look at ourselves and re-evaluate our criminal justice specifically by asking ourselves, why do small crimes warrant steep punishments?

Part 1- Small Crimes = Big Problems

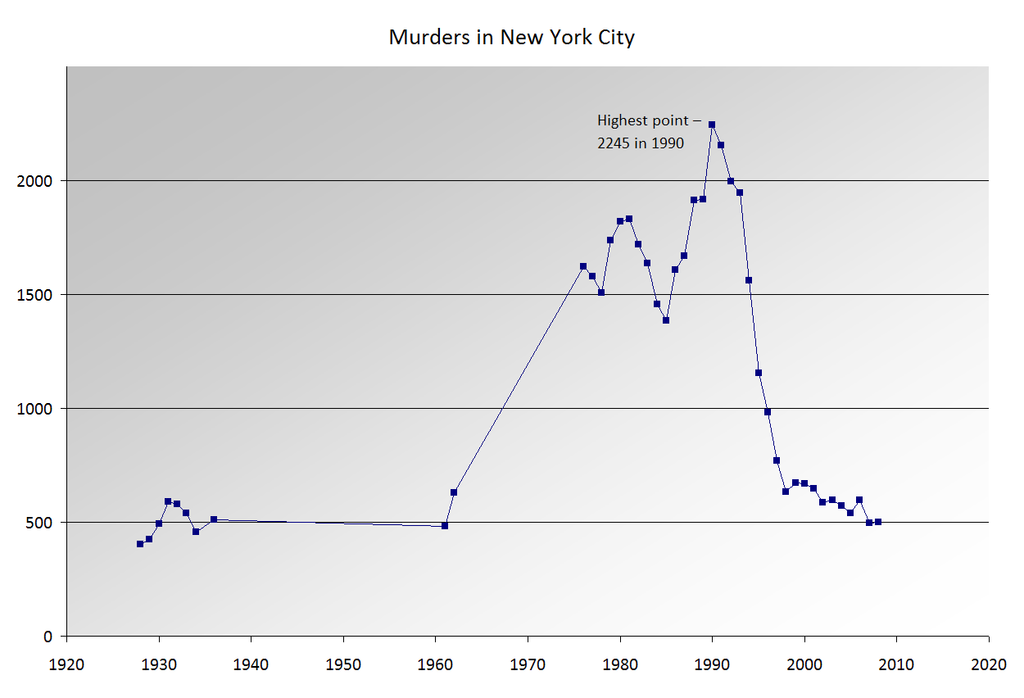

I want to take you back to the early eighties when America was struggling with crime. In fact, it was at the highest point it has ever been since recorded history and in New York City, there was an average of 2000 violent murders every year between 1980 and 1994. In perspective, this meant that during that decade, there were about 5 violent murders per day. Subways were dimly lit and full of graffiti. Streets even in broad daylight were no longer safe. Moreover, both the aids and crack-cocaine epidemics were ravaging the country, and multiple cities, including New York City and Detroit, were brought down to their knees by crime, and on the verge of bankruptcy.

In this social climate, two researchers, George Kelling and James Wilson published an essay in the Atlantic titled “Broken Windows,” which would come to define the national understanding of crime from the eighties to the present day. They argued that cracking down on small crimes would decrease the overall crime rate. Many broken windows in a society indicate that there is something fundamentally wrong with it.

A home with broken windows creates a mentality of neglect, which welcomes crime. The Broken Windows theory is focused on fabricating the idea of order especially if that order does not exist. Kelling and Wilson found that most people are not comforted by an actual lack of crime, they are comforted by the appearance of a lack of crime. Just like how broken windows does not necessarily mean there is crime but it definitely makes it appear as if there was. Appearances are everything. Hence, the researchers caution against allowing a large number of broken windows to exist because the damage it causes spreads with a ripple effect.

The researchers were not addressing a hypothetical scenario; it was a very real problem that many cities in America were facing at that time. Cities just had too many broken windows. The upside of this theory is that broken windows are relatively easy and inexpensive to replace or repair. The researchers recommended certain small crimes like panhandling, loitering and homelessness for governments to focus on.

Part 2- New York City and the Broken Windows Theory

So they city did exactly that. In 1994, with Mayor Rudy Giuliani and police commissioner William Bratton at the helm, the city cracked on small crimes in the city like squeegee men, graffiti artists, loitering, fare evasion, and littering. They ordered policemen to patrol subway entrances and had plainclothes officers prop open emergency doors, arresting all opportunistic New Yorkers who passed through them. Bratton later introduced the morally and constitutionally dubious “Stop and Frisk” program and aggressively used it to target “suspicious individuals.” They also cleaned up the subways and systematically removed graffiti in the subways. By doing all of this, they had changed the appearance of the city and by the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, there was a marked decrease in crime.

However, Giuliani claimed all the credit for himself and his reforms. But note that Giuliani became mayor in 1994 and crime peaked in 1990 but had been decreasingly steadily every year since then. In fact, falling by 400 murders in the year from 1993 to 1994. It is inconclusive if he was the man who reduced crime. In my opinion, Ed Koch, who was the mayor of the city in the eighties, should rather be given the credit for saving the city because he managed to maintain city morale and keep the city alive through very difficult times. Furthermore, many other factors such as the end of the crack cocaine epidemic, the removal of lead from city pipes, and the increase of immigration from East Asian countries may have influenced the decline of crime.

Part 3- The Future of Criminal Justice Theories

Nevertheless, this is the 21st century. We aren’t in the eighties. We don’t have a problem with vandalism. We don’t have a rampant homeless problem. Crime in New York City is at the lowest point since 1928, when the population was a fraction of what it is now. Those broken windows have been fixed.

Yet why did Eric Garner have to die? He was the victim of a theory made for another decade, a more dangerous and violent decade. Some suggest that if we were to stop aggressively prosecuting small crimes, violent crime will make a comeback and I have two things to say to that notion. First, there is inconclusive evidence that the broken windows theory, in fact, did anything for crime. Secondly, the prosecution of this theory falls almost exactly on racial, social, and economic lines. Poor minorities, in particular blacks and Hispanics living in bad neighborhoods, are disproportionately affected by broken windows policing. They are the ones targeted by Stop and Frisk; they are the ones who have no other choice but to hop turnstiles to get to class.

Notwithstanding the theory’s faults, we should not discount this theory entirely because it has great potential for good if executed correctly. Its novel approach to crime is powerful in the way it attempts to change the atmosphere and psychology of people rather than using brute force. But we have to realize that there isn’t one end-all be-all weapon to fight crime and that we have to adjust our plans according to the occasion and local environment. We need to understand the broken windows policing is just one weapon in our large arsenal, used only when necessary. Lastly, when broken windows policing is used, it should only be used mildly. This means setting restrictions on what police can do to innocent citizens.

This means no chokeholds, no stop and frisk. This means we don’t lose sight of our humanity when we go after those small crimes. This means that we fix the windows with an eye on those around us.

Only then can we ever start to do Garner justice.

Great idea, thanks for sharing.