On November 24, a Russian fighter jet was shot down by Turkish forces. On November 13, a coordinated attack by ISIS agents in Paris killed over 130 people. On October 31, a Russian civilian airliner flying over the Sinai Peninsula to Moscow was downed, killing 224 passengers and crew. These events are disturbing symptoms of a much wider conflict that spans the Middle East, one that stems from civil war in Syria, oppressive governance of Iraq, and geopolitical failings of the United States and other countries in the region.

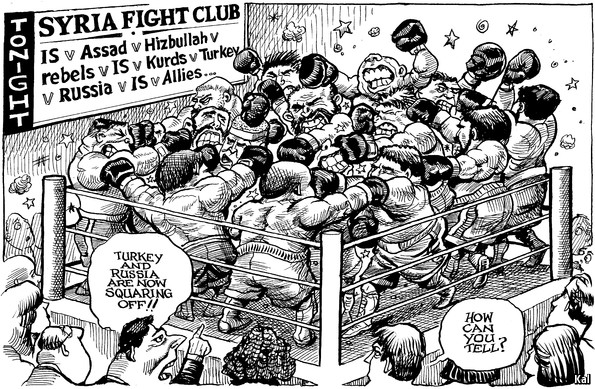

Syria has been in civil war since 2011, arising from the Arab Spring, a democratic movement that swept the region. While the movement has produced transitions to democracy in the countries it spread to, it led to a brutal conflict in Syria. An estimated 220,000 have been killed, over 7 million internally displaced, and over 4 million refugees, many of whom have fled to Jordan and Europe. What began as an arguably noble struggle between a tyrannical government and those yearning for freedom has devolved into one of the worst wars of the century, with a whole mess of extremist Islamist groups vying for power. President Bashar al-Assad still rules and those who oppose him are either too weak or too busy fighting themselves. He is successfully pursuing a strategy of keeping everyone else weak enough to prevent any one individual group from challenging him.

In this humanitarian crisis, outside actors have entered the stage. Of all the opposition groups in Syria, ISIS is the most prominent. It is a terrorist organization borne out of the oppressive and brutalizing regime of the former Shia president Nouri al-Maliki of Iraq and is inspired from the ultra-conservative brand of Islam of Wahhabism, the official sect of Saudi Arabia. Founded by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and under an ill conceived notion of reestablishing an Islamic caliphate, ISIS has emerged as one of the most dangerous terrorist groups in the world; it overshadows others in the region in terms of religious extremeness and scope.

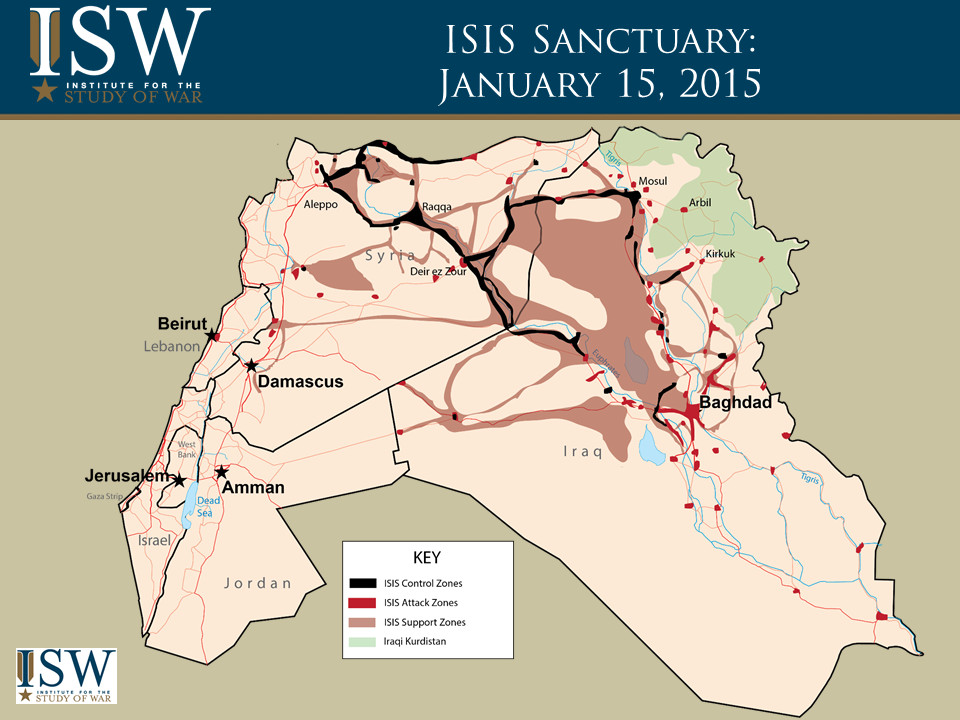

It initially took over territory from Iraqi security forces that were both unprepared to deal with an insurgency and disheartened by a PM and government that was oppressive against the Sunni Muslims of the country. It then established its foothold by delivering security and services to locals in a way the government had failed to. It provides employment and opportunities for people who were otherwise marginalized by an exclusionary government; it schools and trains children in its territories; it creates religious and secret police forces to govern its people; it also terrorizes anyone who does not subscribe to their extreme version of Islam. This includes ethnic minorities, such as Yazidis and Kurds. It has stolen caches of Iraqi army weapons, many of which were paid for by U.S. tax dollars, and stolen oil fields that it uses to finance its operations. Recently, it expanded into Syria, taking advantage of the lawlessness and chaos and established its capital in Raqqa. ISIS has effectively created its own country that spans two failed states.

Russia is yet another actor to have entered Syria. Spurred by a desire to distract the world from the annexation of Crimea and to protect one of Russia’s few allies, President Vladimir Putin has gambled on Assad. He has provided ground and air support against all those who oppose Assad, including ISIS, but his forces have also been striking American air support in the region.

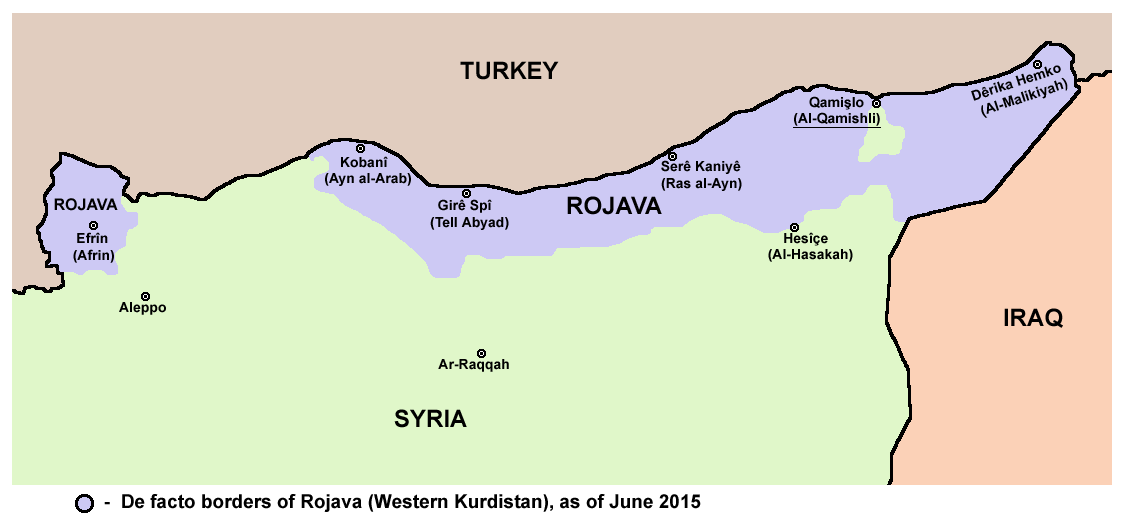

The United States has been conducting an aerial campaign of its own against ISIS and supporting more moderate rebel forces in the country, such as the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG). President Obama has made it clear that he will not engage in a ground war in Syria on behalf of the rebel groups. Neither will he embrace arming and training all those who would want to fight Assad; we did that once in Afghanistan when the Soviet Union invaded and that indirectly led to the rise of the Taliban. These decisions are his presidential prerogative and history shows that action can have dire consequences; regardless, current events show that inaction has its own consequences.

The absence of American leadership has allowed Russia to step in for its own interests, thereby making the crisis ever more complex. Turkey’s downing of a Russian fighter jet exemplifies this. The incident resulted from the jet flying into Turkish airspace. Turkey responded with force. Although the two parties have said they will not go to war, the region has become a powder keg. Countries that do have a stake in resolving the conflict have apparently decided that they each have higher priority concerns of their own.

Turkey is one such country. It has received a flood of refugees since the civil war began. It warmly embraced them at first, but that generosity has since dried up. It is now more alarmed at how the Kurdish people of Syria have become empowered in fighting Assad. The Kurds are an ethnic group scattered across Iraq, Syria, and Turkey. Throughout history, they have been systematically denied a state of their own and often deprived of civil rights. In the wake of the civil war and the rise of ISIS, many Kurds have become armed fighters, many of whom have inspired the Kurdish party in Turkey known as the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Turkey now fears what it cannot control. Turkey has long classified the PKK as a terrorist organization; now it says the same of the YPG. In fact, Turkey began an aerial campaign against the YPG in the city of Kobane in northern Syria, despite the fact that the U.S. officially supports them. Turkey is clearly more worried about its Kurdish minority gaining autonomy than resolving the black hole that is Syria.

Saudi Arabia is another major country in the region that has other interests. Through the past four years, Saudi Arabia and other wealthy Gulf countries have exhibited absolutely no desire to take in refugees. In fact, none of the wealthy Gulf countries have. They have provided minimal air power of their own and little aid to relief efforts. Instead, Saudi Arabia is more interested in its oil revenue: crude oil prices in the global market have dropped to record lows because of a renaissance of American oil production. Shortly prior to that renaissance, Saudi Arabia increased oil production to compensate for economic sanctions placed on Iran and it never reverted back to normal levels.

OPEC members, led by Saudi Arabia, have refused to lower oil production. The logic for OPEC is to continue to pump oil out in the hopes that such low prices will drive out all other competitors in the free American market before they are driven out themselves. Now, the global market is flooded with oil from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other OPEC countries. With Iran poised to reenter the market because of the recently passed nuclear deal, prices are set for another nosedive. All this is bad news for Saudi Arabia, which depends on oil revenue to appease its people and survive. Rectifying this problem is a far more immediate situation for Saudi Arabia than the Syrian civil war.

Saudi Arabia is also involved in Yemen, where another civil war is raging between government forces and Houthi rebels that support a former Yemeni president. Saudi Arabia is engaged in an aerial campaign against Houthi forces. If this sounds similar to the Syrian conflict, it’s because it is. This conflict, however, is not reported on as much because it is comparatively contained and has not produced a humanitarian crisis on the scale of Syria.

Likewise, Iran has business and oil related interests that keep it busy. Officially, Iran supports and provides weapons to the Assad regime. Though Syria is a majority Sunni country, Assad and the ruling minority are Alawites, a specific group of Shia Muslims. As the only majority Shia country in the Middle East, Iran supports the Assad regime, which in exchange provides weapons smuggling routes from Iran to the terrorist group Hezbollah. Iran has backed Assad from the start, but its attention is wavering. With the passage of the nuclear deal among the U.S., Iran, and several other countries, sanctions will slowly be phased out. This will allow Iran to start exporting its oil to the international market and for a flood of businesses to come into the country. Iran is heading towards integration with the international community. Many analysts say that it will not do anything too drastic in the short term to jeopardize this fact. It is, however, entirely plausible that it will use some of the revenue from increased business to fund Assad and thereby work against the U.S.

France is now the latest actor to have entered this overcrowded stage. Reeling from the terrorist attacks in Paris, President Hollande has declared war on ISIS and stepped up aerial bombings on Raqqa. Of course, this has resulted in the deaths of several civilians as well as ISIS agents. France’s military power, however, is quite limited. European members of NATO are notorious for keeping their defense spending lower than what is actually required by NATO. France is no exception. Truthfully, France is riding off the coattails of U.S. power and much of the rhetoric regarding the downfall of ISIS is nothing more. The same can be said of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries.

So where does this all leave us? Clearly, there are a million and one players involved here, all with their own interests. If we are to limit our tactical goals to the containment of ISIS, we can accomplish that quite well. Our military prowess is still the greatest force in the world and continued air strikes will ensure the disruption of ISIS activities within their own jurisdiction.

Arming groups in Syria and Iraq that are opposed to ISIS is another measure, although a tricky one. The historical precedent is the U.S. arming of the Mujahideen forces in Afghanistan when the Soviet Union invaded. Tactically, that was a successful move, but it also led to eventual rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan, from where al-Qaeda launched the September 11th attacks. Doing a similar move in Syria may or may not produce such unintended consequences, as such things only become clear in hindsight.

Such measures, however, will not defeat ISIS. Although ISIS is in fact a terrorist organization, it encompasses more than that: it is an idea of resurgence of the Middle East, a region that was once the epitome of civilization. It is a means to restore dignity and fight back against tyrants and despots and the infidels. It governs and provides services, employment, schooling, and opportunity for people who would otherwise starve. Ever since the end of colonialism and the discovery of oil, these things are exactly what several Middle Eastern governments have failed to provide its people. It is the reason why ISIS is so deeply reviled by most successful Muslim majority countries, but embraced by some of the worst Middle Eastern countries. And right now, it is winning. In order to defeat ISIS strategically, the U.S. must fight the idea of ISIS. Moderate Muslims in the region must be empowered, not just with Kalashnikov guns, but with ideologies. Effective and inclusive governments must be built from the ground up in Iraq and Syria. This is not impossible and to suggest otherwise is insulting: Indonesia is the largest Muslim country in the world and is a successful, pluralistic democracy. The Middle East had already reached that height once before without outside interference and it will have to do it again.