The world average fertility rate has fallen to approximately 2.5 children per woman, while the world population is expected to increase to over 11 billion by 2100. These two facts tell a layered tale of global population trends that is split by economic development. The least developed countries will see the greatest population increase, while the developed world and China will see either a population plateau or an outright decline. This will fundamentally change the world economy from its current phase of boundless cheap labor to something else entirely.

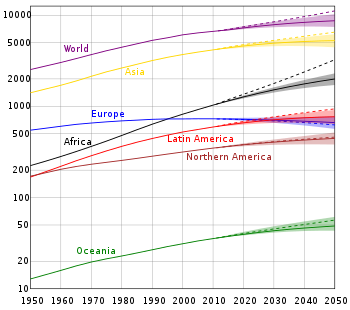

The United Nations estimates that Africa will experience the greatest proportional increase by the end of the century. From its current population of 1.1 billion, the region will double to 2.2 billion by 2050 and then again to over 4 billion by 2100. Nigeria specifically will account for the greatest growth and will soon become the third most populous country in the world. Europe, on the other hand, will experience the greatest decline from its current 742 million to a projected 675 million by 2100, with the largest declines concentrated in Germany and Russia. One example is the difference between Tanzania and Spain: each currently has a population of 48 and 46 million respectively; by 2050, those numbers will be 138 million and 48 million. Tanzania will have more than tripled while Spain will increase by a mere 2 million.

This illustrates Africa’s huge growth, similar to what Asia underwent by the turn of the 20th century. Asia, however, will start peaking this century: China will peak at about 1.4 billion within the next decade; Japan will start declining; and India will continue to grow and reign as the most populous country. Latin America is by far the slowest growing developing region, increasing from its current 599 million to 740 million by 2050. This is due to low fertility rates and high rates of family planning. Of all the developed regions, only North America will experience sustained population growth because of immigration.

Across the developed world and in parts of Asia, we are witnessing a slowdown of population growth and an aging of the existing population. The former is primarily attributed to increased opportunities for women: when women receive the chance to pursue academic and professional goals, they often have fewer children, until average fertility rates dip below its sustainable rate of two children per woman. The latter is because of better quality healthcare. Greater access to more and better medicine is extending the average life span of people in the developed world.

These two thresholds are directly correlated to economic development. China is reaching these thresholds regarding its own population while Russia, Japan, and parts of Europe have moved beyond that phase into population decline. Africa and India are the only major regions to not hit these thresholds, but they will before 2100 due to economic growth.

Until now, the world economy has depended on an endless supply of cheap, unskilled labor. Free trade agreements and the elimination of trade barriers worldwide have precipitated the offshoring of manufacturing jobs from the developed world to emerging markets, where corporate manufacturers were enticed by low production and labor costs.

While it is true that this has harmed the American worker and makes for a great political sound bite, there are shades of gray: offshoring has provided the American consumer with higher quality goods at much cheaper prices, while millions of people in the developing world have been provided with manufacturing jobs they may not have received if companies had more difficulty doing business abroad. These manufacturing jobs, however, entail unskilled labor and not all developing countries have made the investment in human capital needed for its working age population to transition over to higher end manufacturing, such as building cars and machinery.

As population rates stabilize and decline across much of Asia, labor costs will rise and make such markets less desirable to operate from. This threatens to upend the current system in the long term. Low cost manufacturing could conceivably be off-shored again to growing African countries, but it would only be a short-term fix to a problem that is rooted in the new reality of human population decline. It would also be politically difficult as many African countries are not party to free trade agreements that made offshoring to Asia so prevalent in the late 20th century.

The global economy will eventually have to find a substitute for cheap labor. Technology will play a key role, as it always does: robotics is a promising alternative as it easily replaces the unskilled worker. Acquiring robotics, however, is an expensive upfront cost but could be cheaper in the long term since a small team of supervisors would only have to be paid.

Additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, is another alternative that could replace low to mid range manufacturing workers. As these kinds of technologies improve and become lower in cost, they will replace the manufacturing worker altogether. The smaller number of people who will be alive at that time will have to rely on another source of employment.

The changing trends discussed above will influence the future of the global economy.