In August 2015, the Shanghai Stock Exchange experienced its worst crash in almost a decade. Trillions were eviscerated, which caused a massive drop in value for some of the richest investors and companies in China and sent shock waves around the world. In the final weeks of December 2015, the United States Federal Reserve (the central bank of the US) announced its first interest rate hike in seven years on the basis of an improving American economy. In the first week of January 2016, the Chinese stock market crashed once again, causing the worst opening of international stock markets in a new year ever recorded. These events tell a story of an international economy that is intertwined for good and bad; it is a product wrought by globalization.

The Chinese economy has been slowing down for quite some time, and most likely will continue to decelerate. For over two decades, China achieved stellar, double digit growth rates. This led to the rise of hundreds of millions from poverty and the development of specific sectors of China’s economy. It also created a dismal situation for workers’ rights, produced grotesque pollution, and exacerbated inequality, particularly between coastal areas and impoverished inland regions. For almost 20 years, China was the engine of economic growth for the world, proving to be a bulwark even during the global recession of 2008. This dynamic, however, is changing. The Chinese economy is slowing down, with official growth rates struggling to hit the 7% forecast for 2015.

The primary concern, among many, is the slowing growth of Chinese exports that supply the world with cheap consumer goods. To combat this, the central bank of China, which is an inherently political institution of the Communist Party, intervened by devaluing the Chinese yuan against the American dollar. By lowering the value of the yuan, Chinese exports are made more competitive against exports of other countries with higher value currencies, thereby making Chinese goods more compelling for consumers abroad. This devaluation, however, defies the international standard of letting financial markets freely determine the value of another country’s currency. It also panicked investors by explicitly letting them know that the Chinese economy is in trouble.

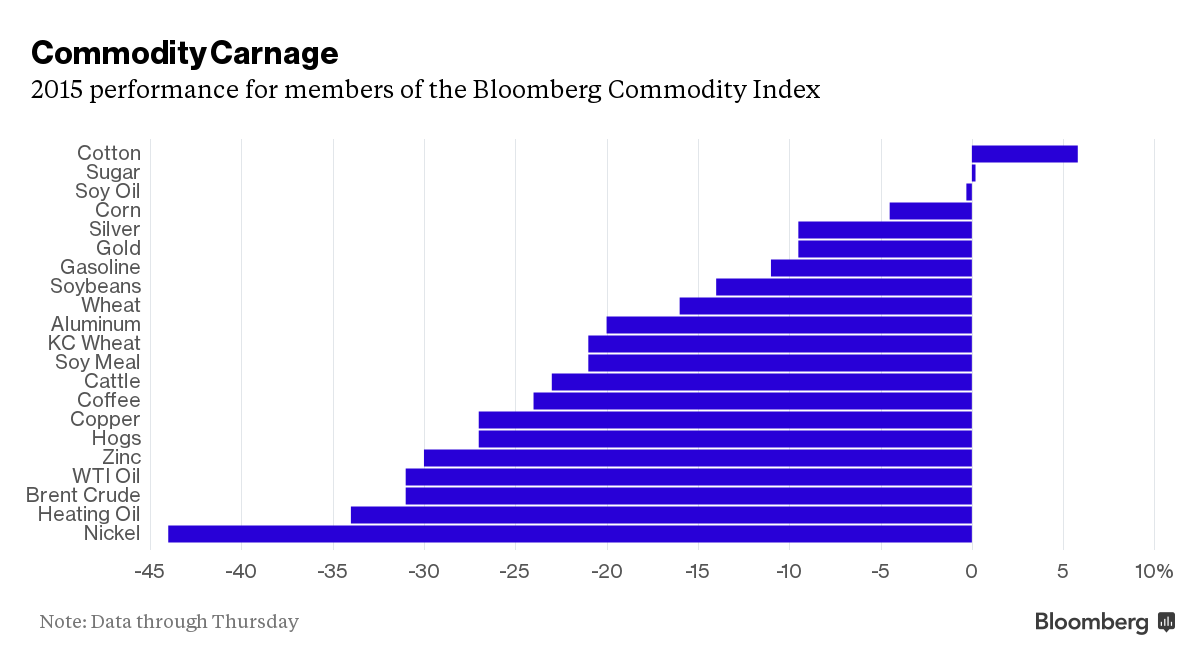

The People’s Bank of China devalued the yuan against the dollar twice in August and once again in January. While the devaluations were tactical moves by the PBOC to allay the exports problem, they alarmed investors, which caused massive sell-offs around the world and two stock market crashes. They also introduce problems of their own. Commodities all over the world are denominated in dollars. Raw materials like minerals, gold, copper, oil, and metals are usually priced in dollars regardless of whether an American is involved in the transaction. If financial markets change the valuation of the dollar, it only marginally affects the buyers and sellers of other countries (supply and demand move around because reasons). However, if a government artificially lowers the value of its own currency, it winds up paying more for commodities. China has become a massive consumer of commodities, much of which comes from Africa, to power its economic growth. Of course, as overall economic growth slows, the demand for such commodities will also slow, but what it does buy may be more expensive because of the devaluation.

Intervention of the PBOC is also behavior unwelcome by the international community. Starting in October 2016, the renminbi, another name for the yuan, will join the Special Drawing Rights (SDR), a basket of foreign currencies designated by the International Monetary Fund. This basket is composed of currencies that are used by countries and corporations everywhere when making transactions and are the forms in which most wealth is stored. It includes the US dollar, the British pound, the Japanese yen, the Euro, and (soon) the Chinese yuan, which means these are the most prolific currencies. One of the conditions for entrance into the SDR is transparency in monetary policy and allowing financial markets to determine currency valuation. The Communist Party has maintained an iron grip on the value of the yuan for years in order to bolster exports, which many criticize as an illegal trading practice. As the yuan joins the SDR, though, the Communist Party will supposedly relinquish control and eventually cease intervention. Interestingly, the recent devaluations are not contradictory to this statement: many experts believe the real worth of the yuan is actually lower than it is now. The Communist Party may have artificially set the bar, but it is still closer to where it should be now compared to before. What is contradictory is the intervention itself. China will not release full control yet because it could lead the economy even more downward, but it should soon.

The stock market crash has social ramifications too. The current slowdown will likely not recede. One way the Communist Party has dealt with it is by making a scapegoat of some of the wealthiest citizens of China. In recent months, hedge fund managers, CEOs, and other successful people have been detained and interrogated for a variety of crimes, including falsifying financial reports. While it’s reasonable to believe that at least some corruption exists, it is bad for business to detain prominent individuals for political reasons. For all the bad they may have done, these men and women have in fact provided much of the economic growth of China. If standards of integrity are to be used, they must be upheld at all times, not just when it is convenient for a one-party country like China. Stock market crashes also worry ordinary Chinese citizens, who must increase consumption in order to develop their country as an economically stable market. In the same vein, the financial services industry needs to continue growing as well. These latter points are critical as China must move away from the debt fueled investments it has used to power its economy towards consumer spending. This will ensure continued growth of the economy while slowing the growth of debt. The rise in interest rates by the US Federal Reserve may help in this regard.

For over seven years, the Fed has kept interest rates in the US at a bare minimum. This kind of monetary policy encourages greater borrowing from banks. Individuals looking to buy a home and companies looking to engage in new investments have benefited from low interest rates, causing a flood of American cash to enter various markets. By encouraging borrowing, the Fed hoped to improve the American economy. This strategy, called quantitative easing, worked to an extent. Much of this money found its way to the developing world, which in turn financed a lot of economic growth. Firms in China, for example, were able to attain American money to expand, but they also accrued significant debt.

Being in debt, whether on a micro or macro scale, is not necessarily a bad thing. People usually take out loans to acquire material possessions or start businesses. Companies take out loans to start new projects or expand. So long as a steady stream of income ensures that payments are made to pay back loans and interest, being in debt is not bad. In fact, it’s actually good, because it means that an economy is active, but there are limits.

On a micro scale, individuals can set their own limits. On a macro scale, it is typically bad for countries to have a debt-to-GDP ratio larger than 100%. GDP is analogous to measuring how much a country is worth, in a monetary sense; a ratio larger than 100% is like saying that a country owes more than it is worth. China is a corrupt one-party state where official facts and figures are dubious at best. Unofficial studies, conducted outside the Communist Party, estimate that the debt-to-GDP ratio is almost 200%. Much of that debt was accrued during the era of cheap American money. That era is not yet quite over, since the Fed only increased interest rates by a bit (~0.25%), but it should discourage borrowing. As the economy slows, corporate revenue takes a hit and a company becomes hard-pressed in repaying its loans. If the debt-to-GDP ratio is in fact 200%, China may be in a credit bubble of giant proportions. The government can’t help every company, which means that many will go bankrupt. What remains to be seen is how bad of an impact this will produce for China and the rest of the world. What will happen when this bubble pops?

The global economy will likely go into panic mode, as it did in August and January, although the degree of that panic may be far worse. It could be as bad as it was in 2008, when the US thrust the entire world into recession. This time, however, the US is in much better shape now than it was before. The unemployment rate is below 5%, there are many realms of advanced technology that promise economic expansion, and wages are finally increasing, although just barely. Perhaps one of our biggest dilemmas is the extreme partisanship in Washington DC. Still, we are in much better shape than we were in 2008 and could potentially weather an economic storm wrought by China. Who that storm will affect the most, though, is the European Union, which is China’s biggest trading partner. Various commodities suppliers, mostly in Africa and Central Asia, will also hurt as demand slows in China.

If the the Chinese credit bubble does pop, then the volatility could be far more encompassing than the current market turmoil. The present situation is confined to the global stock market, which is always a lot more volatile and unstable than other economic sectors. As an old adage goes, “the stock market has predicted nine of the last five recessions.” Financial markets are unreliable as fortune tellers and investors have a tendency to overreact. Moreover, China is in fact doing many of the things that it needs to do to transition: consumer spending is increasing, borrowing is going down, and the Communist Party is (slowly) releasing control of the yuan. But the era of high economic growth is likely over. It will take time for people to get used to that.

One final note: this is all a result of a more connected world. Why is it that what happens in one place affects things everywhere else? How can some numbers and charts that don’t move the way people expect make everyone panic? It seems quite absurd when you take a step back, but that is what happens when a global economy joins to the hip. It is a result of globalization, a glorious process that connects us all and makes our world perceptibly smaller, for good and bad.

1 thought on “Hold Tight and Don’t Panic”