Warlimpirrnga Tjapaltjarri, an artist whose work is currently being displayed for the first time at the Salon 94 gallery in New York City, is not your typical small town artist looking for fame. In fact, until he was in his 20s, Mr. Tjapaltjarri belonged to the Pintupi Aboriginal group, in a West Australian desert. When the Pintupi were forced to move into settlements in the 1950s and 1960s, his family remained out of view, “hunting lizards and wearing no clothes except for human-hair belts”. In 1984, Mr. Tjapaltjarri and his family were discovered and moved into a Pintupi community. They were a sensation in the news, known as the Pintupi Nine, the last “lost tribe.”

Mr. Tjapaltjarri took on painting with his two brothers, modifying traditional designs that Pintupi men used on rocks, spears, and bodies. As a healer and keeper of ancestral stories among the Pintupi people, Mr. Tjapaltjarri captures the history of the natives in his art. His abstract style, which has made him famous in the Desert Painting Movement, is seen as unique and fascinating to many. Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn, the owner of the Salon 94 gallery, said that she first saw Mr. Tjapaltjarri’s work in the remarkable Documenta exhibition in Kassel, Germany, in 2012, and his paintings stood out the most. “I also loved the fact that this abstraction had another kind of abstraction behind it — at least abstraction to us, because we’ll never be able to understand these stories in the way they do,” she said. “And I thought that they looked so contemporary at a time when abstraction is being practiced by so many New York artists.”

The unusual history behind Mr. Tjapaltjarri’s art is what makes it so exceptional. Every painting has a story behind it, although not every story is revealed to the public. The way the artwork tells a story has remained a secret. Fred R. Myers, an anthropologist at New York University who has studied the Pintupi and their art since the early 1970s, says, “I’ve been asking that question for 40 years, and I’ve never really gotten the same answer twice — it’s very inside knowledge, the paintings operate more like mnemonic devices than like representations of a narrative.”

Regardless of his growing fame, Mr. Tjapaltjarri will always be an important figure among the Pintupi people. In Kiwirrkurra, the community where he lives in the Gibson Desert, he is well respected for his knowledge and experience. His artwork tells the mythical stories about the Pintupi people as well as about the formation of the desert. For example, one of his paintings, which may simply look like lines and curves, tells the story of a group of ancestral women who appear only at night in the desert around Lake Mackay, an immense saltwater flat that is the main focus of his paintings. His art has a deeper meaning, one that may or may not be understood by everyone, but holds a place in the hearts of the Pintupi.

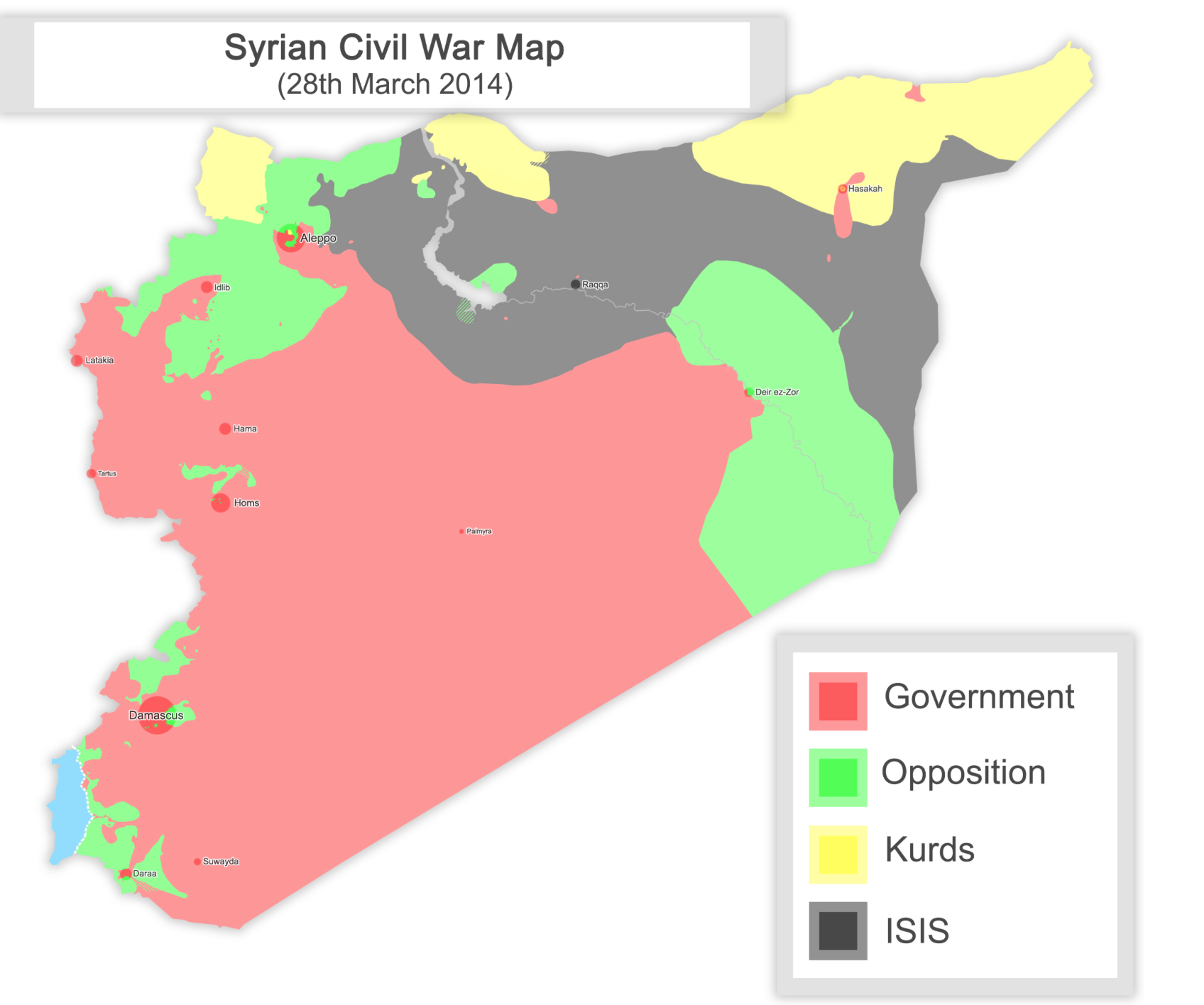

Each day, thousands of illegal immigrants are smuggled across the border. They are shoved into gas tanks, squeezed into cargo boxes, and hidden in the backs of trucks.They are pressed into small boats by the hundreds just to be sunk off the coast. News coverage has made us all painfully aware of what Syrian refugees go through in order to enter Europe. Yet with all the focus of the Syrian refugees fleeing the Middle East, why haven’t we asked ourselves what happens to those who stay behind? In his article “Photo Exhibition Puts Syrian Refugees on the Seine,” Elian Peltier features

Each day, thousands of illegal immigrants are smuggled across the border. They are shoved into gas tanks, squeezed into cargo boxes, and hidden in the backs of trucks.They are pressed into small boats by the hundreds just to be sunk off the coast. News coverage has made us all painfully aware of what Syrian refugees go through in order to enter Europe. Yet with all the focus of the Syrian refugees fleeing the Middle East, why haven’t we asked ourselves what happens to those who stay behind? In his article “Photo Exhibition Puts Syrian Refugees on the Seine,” Elian Peltier features

camps. While it is easy to dismiss a suffering adult, a child in pain cannot be so easily ignored. He glamorizes their childhood in certain pictures by capturing the children while playing. It is easy for a viewer to relate to his own childhood in such pictures, and as such he recalls fond memories and develops a connection with the child in the photo. Later photos shock the audience by capturing the children at their low points- while performing physical labor or laying on the ground motionless. According to Reza, “[these] kids have lost the paradise every kid has.” Now in his state of shock, a viewer is more sensitive to the conditions refugees face and will be less likely to dismiss their rights as humans.

camps. While it is easy to dismiss a suffering adult, a child in pain cannot be so easily ignored. He glamorizes their childhood in certain pictures by capturing the children while playing. It is easy for a viewer to relate to his own childhood in such pictures, and as such he recalls fond memories and develops a connection with the child in the photo. Later photos shock the audience by capturing the children at their low points- while performing physical labor or laying on the ground motionless. According to Reza, “[these] kids have lost the paradise every kid has.” Now in his state of shock, a viewer is more sensitive to the conditions refugees face and will be less likely to dismiss their rights as humans.

Recent Comments